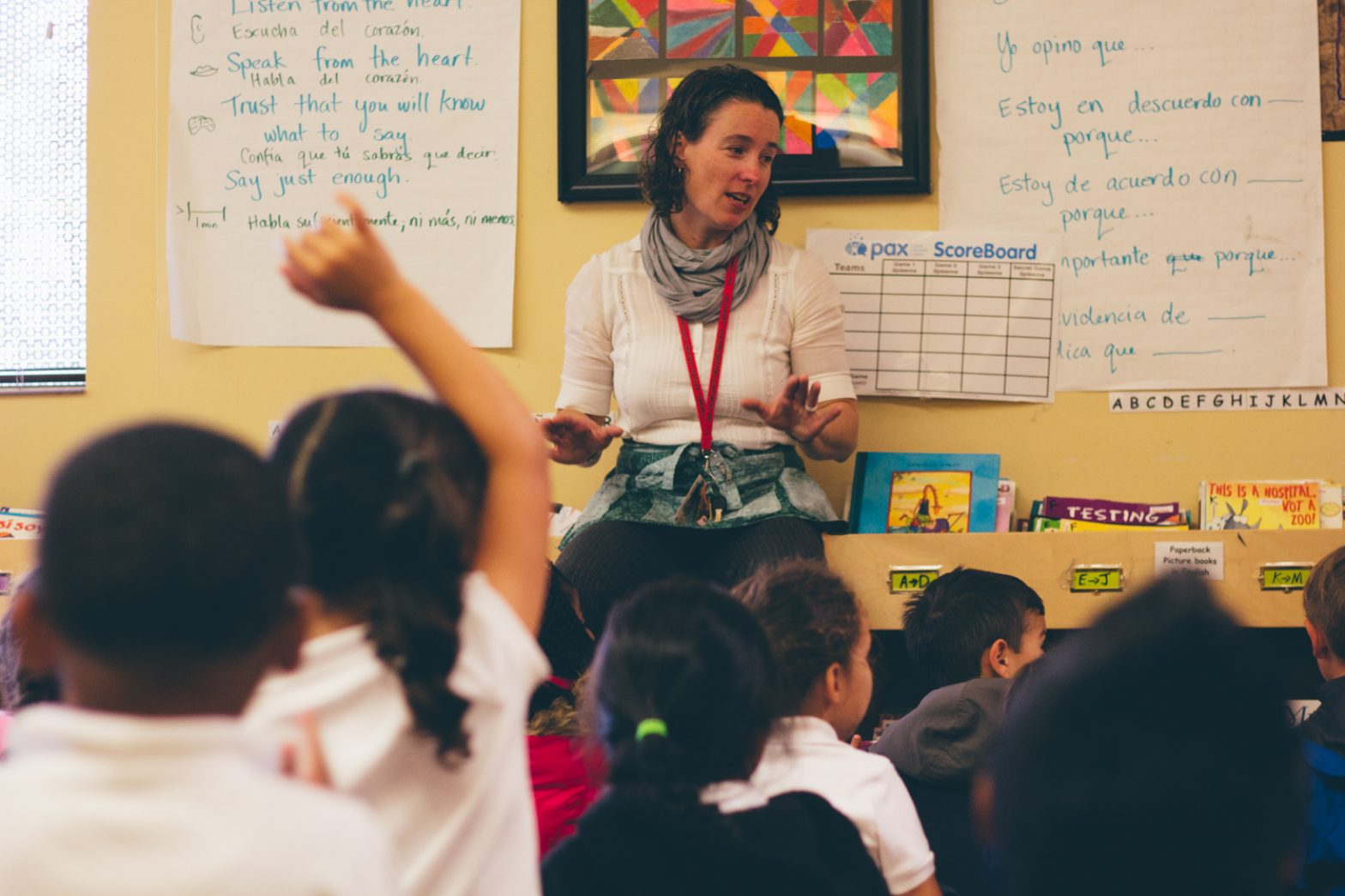

Photo essay: Ana Hernandez, Junipero Serra Elementary; and Barry Schmell, Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy

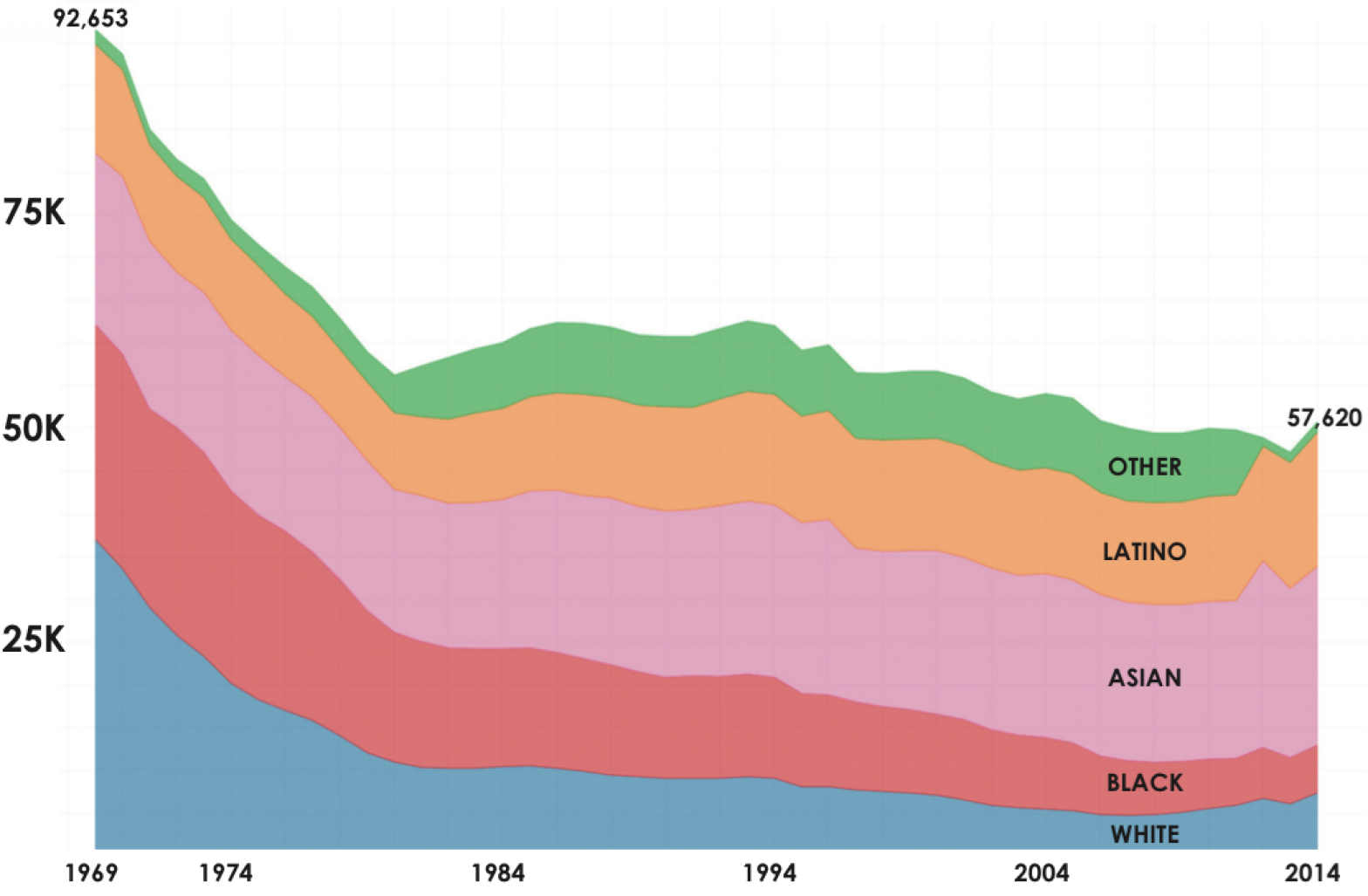

Today, after five years of severe budget cuts in the San Francisco Unified School District, PTAs are being asked to pay for teachers, reading specialists, social workers and school psychologists, computers, basic school supplies, staff training and more. But not all PTAs can afford those things. Parents at just 10 elementary schools raise more than half the PTA money that all 71 elementary schools in the district take in. Many of the rest raise nothing, or almost nothing.

Ana Hernandez and Barry Schmell come from very different backgrounds, but they have at least one thing in common: They both lead their schools’ parent-teacher associations

Part of a special report on education inequality in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the winter 2014 print edition.