Distance, funding cuts and travel costs make it hard for students from low-income families seeking city’s best schools

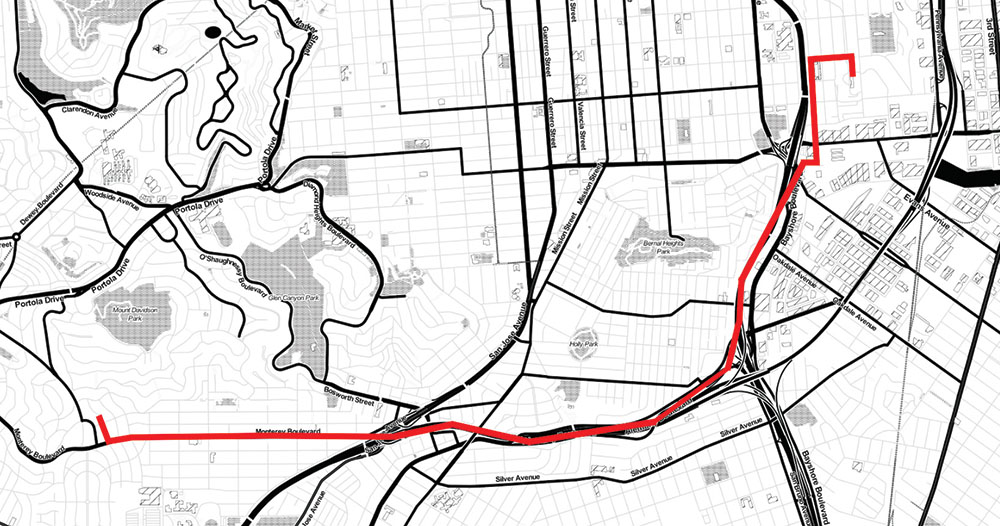

Eight-year-old Karishma Sears started her trek to school with her father in the family car one Thursday in December. It took only 15 minutes to drive from their home near Mount Davidson 4.6 miles to Starr King Elementary in Potrero Hill, where she participates in a highly regarded Mandarin immersion program her parents chose for her. Their jobs are on the Peninsula but both can work from home and help shuttle Karishma to school.

If she had to take mass transit? It would be an hour-long commute each way, even if Karishma were old enough to do that on her own.

While San Francisco’s school assignment system has benefited families with the means to transport their children to schools with the most desirable programs, it creates dilemmas for more disadvantaged students who must travel long distances to school, often without the help of their parents.

Many lower-income students must choose between long commutes on unreliable public transit and attending lower-performing schools closer to home. This may help explain why San Francisco public schools, like those in many cities nationwide, are increasingly resegregating as decades of court-ordered diversity measures recede into history.

At the same time, San Francisco Unified School District data show that most families of all socioeconomic backgrounds travel outside of their neighborhoods for school. There are numerous potential reasons: Their children got into a school they preferred to the one in their neighborhood, or they did not get assigned their neighborhood school because there were too few seats to accommodate nearby residents. But the district lacks solid information about exactly who is trekking across town and why, making it difficult to understand transportation’s effect on school choice.

In a district that lacks robust school bus service, even students who do not get a top-choice school are caught up in public transit headaches when the system assigns them across town.

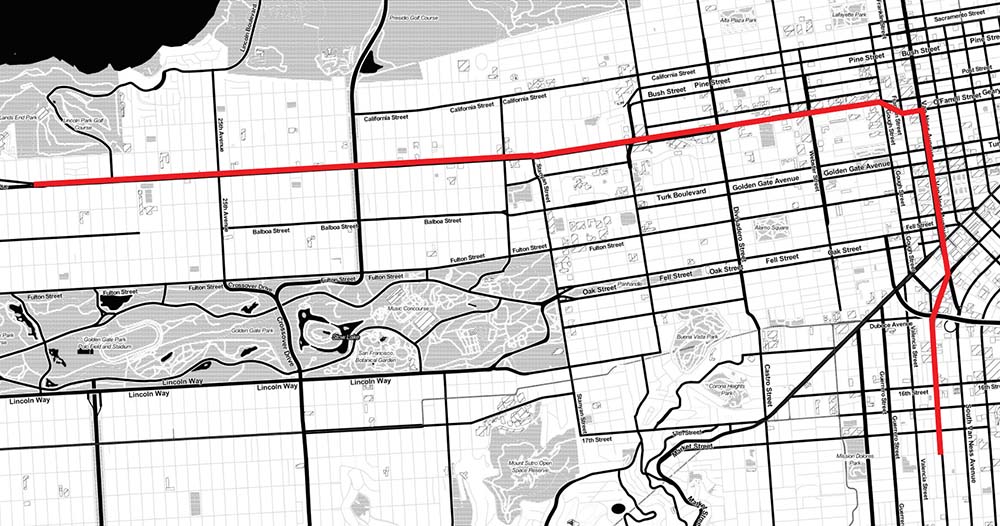

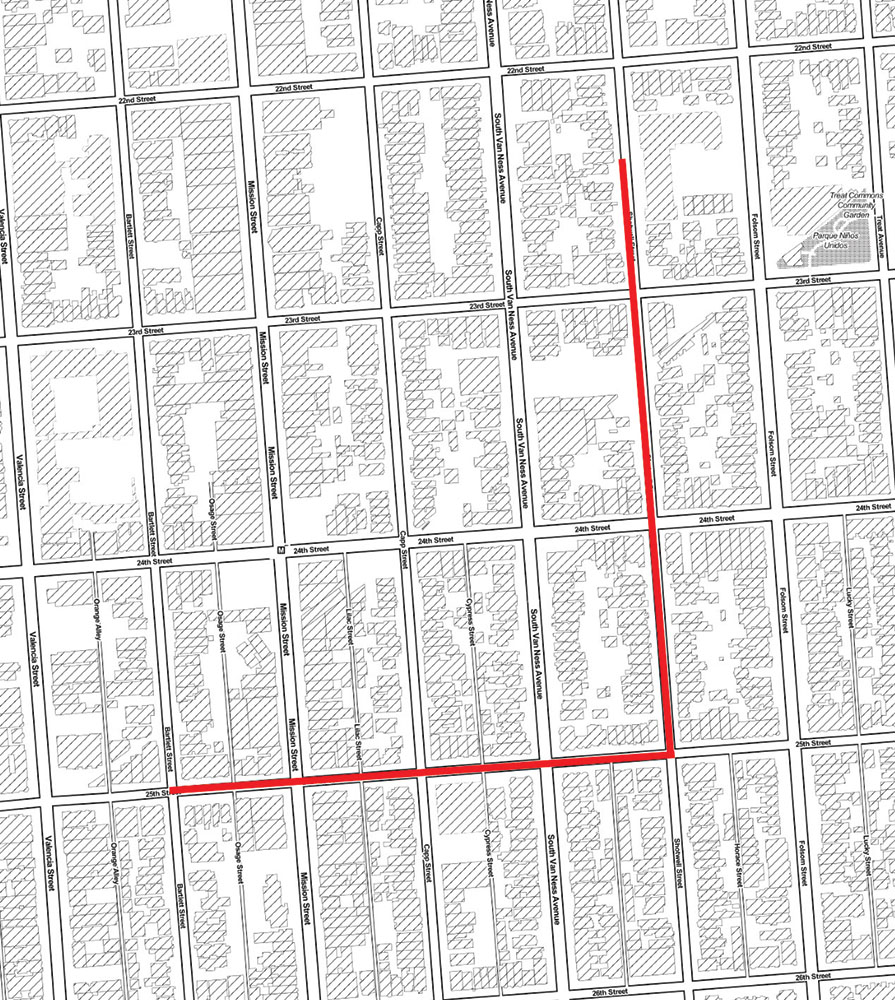

Chris Collier leaves his home in the Richmond District each morning long before sunrise — nearly two hours before school starts. The ninth-grader first takes a bus on Muni’s busiest line, the 38, more than four miles east to Van Ness Avenue and O’Farrell Street. There, he transfers to the 49 for the final two miles to John O’Connell High School in the Mission District.

Chris, 14, had hoped to attend Washington High School, just half a mile from his home. But he did not get his top choice, or any of his choices in the district’s school-assignment system. And he has no one to drive him across town. So his commute takes 75 minutes, at best. When the 38 is overcrowded and he cannot squeeze in, he risks being late for his first-period English class.

San Francisco Unified School District in 2010 adopted a student assignment system intended to increase diversity and give all families access to the best schools. The policy lets parents select schools they like the most, creating competition. It is a contest that not everyone wins.

Equity challenges

Daniel Sears, Karishma’s father, knows his daughter is lucky. A group of recent Chinese immigrant families in Visitacion Valley who wanted to send their children to Starr King could not, because they had no way to get them there. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency — aka Muni — does not offer direct service, and no school bus runs that route.

The district prioritizes bus service for its most disadvantaged students, including those who live in census tracts with the lowest test scores: Treasure Island, parts of the Tenderloin, the Western Addition and most of the southeastern neighborhoods.

But the district does not transport elementary-age students from more affluent areas to schools in low-performing neighborhoods, while the buses that serve most lower-performing schools pick up kids who live in nearby neighborhoods.

So the Visitacion Valley families lose out two times over: their schools perform below average, but not at the bottom, and the school they wanted to attend is in a neighborhood to which the district will not bus their children. Thus, isolation and inequity persist, bus or no bus, for all kinds of students.

“What we’ve heard from families, especially in the southeast neighborhoods, is that while we have choices as to where to send students, getting them there is a barrier that’s too high to overcome,” said Masharika Maddison, executive director of the nonprofit Parents for Public Schools, which advocates on policy for families throughout the school district.

Joel Ramos, regional planning director for the mass transit advocacy nonprofit TransForm and a board member of Muni, said many families simply cannot use public transit to get their children to school.

“Even if you can get into a school that’s performing much better but is on the other side of the city, a trip on Muni might require one, two, even three transfers,” Ramos said. “A lot of people aren’t going to feel comfortable letting their kids do that.”

District data, collected by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, show that few students have changed their commute patterns since 2010–2011, the year before the current assignment system took effect.

At eight of the 25 district elementary schools with below-average statewide academic rankings, the number of students who live within a mile of school has increased over the last four years. With few exceptions, a significantly higher percentage of these students live closer to school than do students at the highest-performing and most-requested schools.

While a number of factors are at play, lack of mobility looms large. Even though families of all socioeconomic backgrounds are traveling long distances, many schools in the most economically disadvantaged parts of town draw the bulk of their students from the surrounding neighborhoods.

Student populations at some of these schools are so imbalanced that the district considers them “racially isolated,” meaning that more than 60 percent of the school’s students are of a single race.

Public transit poor substitute

Rosario Bolos walks her daughter, Jessica, three blocks from their house to Cesar Chavez Elementary in the Mission. She knows it is one of the city’s lowest-performing schools. But she likes its feeling of community, and her top priority when choosing a school for Jessica was, by necessity, its proximity to home.

“We can’t afford a car, and my husband works full time, so this is the only choice we have,” she said. She does not let Jessica, 6, ride Muni alone. “That’s for older kids.”

As part of its effort to align its transportation services with the new student assignment policy, the district cut its fleet to 25 buses last school year, down from 44 buses in 2011–2012. As a result, 20 schools lost all bus service, and service to many others shrank or changed. The district does not plan more cuts or additions, according to school district spokeswoman Heidi Anderson.

As school board member Rachel Norton sees it, every dollar spent on busing is a dollar taken out of the classroom. One bus costs $100,000 to operate and maintain for a year. The money comes out of the district’s general fund, which also covers teacher salaries and operating essentials.

“We don’t have a lot of money, and we have to be careful to invest in the highest-impact strategy,” said Norton, who was first elected in 2009 and now chairs the Ad-Hoc Committee on Student Assignment. “You can pay for a literacy coach and a half with the money it costs to run a bus. Is a bus that carries students to a school without literacy coaches the best strategy?”

Norton said that while the district knows the demographics of students who request transportation, it does not have stop-by-stop data, nor the expertise to design routes that would optimally serve the most students. “We as a district could use some planning assistance,” she said.

Charity buys bus passes

Muni in 2013 started offering free passes to low- and moderate-income San Franciscans ages 5 to 18 through a pilot program funded by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Last February, Google donated $6.8 million to continue the program for two more years. So far, 26,000 kids have signed up.

Chris Collier said it saves his family about $30 per month, and many families praise the program for making the commute to school more affordable.

For families with younger children, who need to be accompanied on public transit, the cost of travel is even more significant because caregivers must pay $2.25 per trip, even if a student qualifies for a free pass. The crowded and delay-plagued Muni system, which gets fewer than 60 percent of buses and trolleys to arrive on time, will bring in millions in new funding to upgrade infrastructure and add service starting this year, thanks to propositions A and B, approved by voters in November. But Muni is not a transit system designed to transport large numbers of students.

As for what families really want, some certainly prioritize community, family history and convenience over test scores when choosing a school. But the district found in a 2012 survey of more than 10,000 families that academic reputation usually trumped proximity to home as a factor. Fewer than half the families responding to the survey included nearby schools in their choices.

And yet, a number of families interviewed for this story chose otherwise. This contradiction demonstrates the difficulty of drawing conclusions about what drives choice patterns in the district.

Data from the 2014 application process shows that half of the 22 schools least requested by families living in their attendance areas are located in the city’s poorest neighborhoods, and eight of them have student populations dominated by a single race.

Further, reports produced by the district show that a higher percentage of African-Americans and Latinos submit school choice applications late than do their Asian and white peers, and by doing so are placed at the bottom of the heap during student-assignment season. This limits their access to the district’s best schools, and can result in assignment to the least-requested schools, which are often in their neighborhoods.

A 2014 report produced by the Denver transit advocacy organization Mile High Connects and U.C. Berkeley’s Center for Cities + Schools, notes that reforming student transportation can be complicated by the sharing of responsibility for busing by local, regional and federal agencies. It can get very political as a result.

Julia Ehrman, a sustainable transportation fellow with San Francisco public schools and a fellow at the Center for Cities + Schools, spent last summer investigating the district’s transportation landscape. She found that there was very little data about how transportation affects families’ ability to take advantage of school choice. But she cautioned against the view that programs intended to promote walking and biking as part of the district’s sustainability goals can replace school bus and transit service for public school students.

“If we only promote walking and biking, then we sort of contradict the premise of school choice: that mobility is a good way to pursue educational equity,” Ehrman said.

Maddison said the biggest problem actually is not transportation. It is the vast disparities among San Francisco schools.

“School choice can never be a replacement for ensuring that all our schools are excellent.”

This story was published in the winter 2015 print edition of the Public Press. For the full report rolling out online through early February, see sfpublicpress.org/schooldiversity. To read the 2014 report on the effects of parent fundraising and (follow-up coverage), see sfpublicpress.org/publicschools.