Roughly two years, multiple eviction moratoriums and over $3.6 billion in rent-relief payments after tenant advocates began worrying COVID-19 hardships would push thousands of renters out of their homes in San Francisco and elsewhere, California policy interventions aimed at preventing evictions are poised to end.

Barring an eleventh-hour postponement by lawmakers (not out of the question, given three previous last-minute extensions), California’s eviction protections expire June 30. Among those vulnerable to being forced from their homes are more than 135,000 tenants whose applications for rent relief have been denied, and thousands more whose applications may be denied in the future or not processed by the time protections are lifted.

On top of that, tenants who didn’t submit requests for relief before the deadline and those struggling to pay rent due after March 31, the date the state stopped accepting applications, have been vulnerable to eviction since then because of the limited scope of Assembly Bill 2179. The bill, passed on March 31, extended eviction protections, but only for some tenants.

San Francisco is now seeing the beginning of an eviction wave of tenants who lost protections after the program was closed or are otherwise behind on rent, warns a tenants’ rights lawyer.

“We’re starting to see numbers escalate in the courts, getting closer to pre-COVID levels,” said Ora Prochovnik, director of litigation and policy at the Eviction Defense Collaborative. “And we’re struggling to keep up with it.”

The organization is one of the primary groups in San Francisco representing tenants in eviction lawsuits and tracks the requests it receives from tenants seeking legal aid.

“We’re just in some uncharted waters right now,” said Tim Thomas, research director at University of California at Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project, regarding how the expiration of California eviction protections will play out.

Evictions are likely to rise after July 1, as landlords who have been waiting for protections to end begin to file the legal paperwork to eject renters, Thomas said, referencing trends he’s observed across the country. He added that lawyers who represent tenants will likely be overburdened with cases.

Rent relief from the California program was intended to aid thousands of tenants at risk of losing their homes for non-payment of rent. More than 15,000 households in San Francisco have received $177.3 million in assistance, according to data from state and local programs. However, those whose state applications were rejected or remain unprocessed as of July 1 will be vulnerable to eviction.

Although the state is scrambling to process all its applications by July 1, as many as 33,000 applicants may still be waiting for help when the last protections expire, according to a report by three nonprofit housing research groups. The California Department of Housing and Community Development disagreed with these projections, citing week-to-week progress updates that show the number of applications moving through the eligibility and approval process. The program will have made a determination for all first-time payment applicants by June 30, said Alicia Murillo, a communications specialist with the department.

Despite disagreements around specific projections, housing and equity advocates expressed concerns regarding an eviction wave.

“We should be worrying about it,” said Thomas. “On a national scale a lot of areas that have seen moratoriums ending have been seeing very large increases in eviction.”

Nearly 100,000 households that are behind on rent or mortgage payments in the Bay Area said that they are likely to be evicted or foreclosed upon in the next 60 days, according to the US Census Bureau’s most recent Household Pulse Survey.

On a national scale a lot of areas that have seen moratoriums ending have been seeing very large increases in eviction.

—Tim Thomas, Urban Displacement Project

Thomas predicts that once protections expire, California will see a slow rise in evictions that gains steam over the next few months. He noted that evictions tend to be seasonal, and that rates often pick up in July.

“There’s something about around that period of time that it just really picks up a lot,” he said.

Nailing down evictions data is “incredibly complex and tricky,” Thomas noted. Although some data is accessible, it’s often incomplete and may not fully reflect the reality of how many people are being forced out of their homes. Landlords are not required to report three-day notices for non-payment of rent, so the number of notices recorded likely represent only a fraction of the total, according to the San Francisco Rent Board. Scheduled evictions by the Sheriff’s Department do not capture the large number of tenants who may be intimidated into leaving by their landlord at various stages of this process, Thomas said.

Though California’s eviction moratorium ended last September and the state’s rent relief program stopped accepting applications in March, tenants who applied to the program and are awaiting a decision or payment are protected from eviction for pre-April rent debt until June 30. And even if they haven’t received the funds by that date, tenants approved by the program can block evictions by providing documentation of their approval from the program.

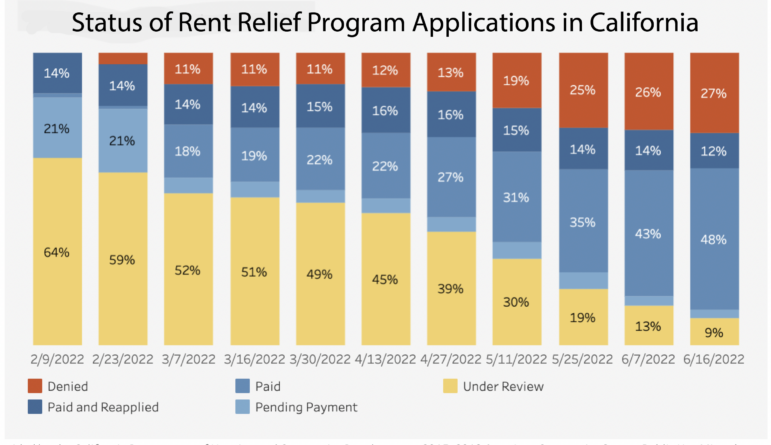

For many, the only thing legally staving off an eviction is their pending application. But once an application is denied, a tenant can be evicted — and the number of denials is on the rise.

Denials and shadow debt

As the state has stepped up its pace in processing requests in recent weeks, denials have jumped, further increasing the number of tenants vulnerable to eviction.

The share of San Francisco applicants whose applications were denied nearly doubled from April 13 to June 16, accounting for 29% of requests, up from about 15% seven weeks earlier. That put the number of applications denied at over 6,300 out of over 21,400 total applications. A tenant can appeal a denial up to 30 days after it has been issued. If a tenant loses their appeal, or does not appeal within the time frame, they can be evicted — even before June 30.

An applicant can be denied for not meeting qualifications, such as exceeding 80 percent of the area’s median income, or for being non-responsive when the state program attempts to communicate with them regarding their application. But a quirk of modern technology has put some applicants in the non-responsive category without them even realizing it, said Antonina Real, a tenant counselor at the South of Market Community Action Network.

Calls from the state program showed up as “Scam Likely” on the phones of some tenants she works with, she said, so tenants don’t pick up or may not call back. This delays the process and can result in denial if the applicant doesn’t eventually respond to the program. When asked about this issue by the Public Press, Murillo said it was the first time the “Scam Likely” calls had been mentioned to the Office of Housing and Community Development.

On top of technological hurdles, tenants with so-called shadow debt, acquired by borrowing from credit card companies, friends, family or even loan sharks to cover overdue rent, can no longer get help from the program, she said. Though the program never officially covered shadow debt, applicants used to be able to apply for up to three months of future rent and use other income to pay off their debt, a spokesperson for the program, Russ Heimerich previously told the Public Press.

In one case, when the tenant’s application was marked by the state as “withdrawn,” Real thought it was an error because the tenant — who had borrowed from a loan shark and credit cards to pay rent — had not withdrawn the application. Real called a case manager at the state program, who said that the program does not reimburse individuals who took on shadow debt to pay rent.

A July report by the University of Pennsylvania found that Asian American and Pacific Islander households have the highest average shadow debt in California, borrowing almost a third more than white households, and double what Black households borrowed. Previous Public Press reporting highlighted potential cultural reasons why certain demographic groups, such as Chinese tenants, may take on shadow debt at higher rates.

“The whole Chinese community shares the same value: They don’t like to owe anything” to the landlord, Rita Lui, a housing counselor at the Chinatown Community Development Center, told the Public Press in October.

Another reason these communities may take on higher shadow debt is because they didn’t know about the existence of the state’s rent relief program in the first place or were unable to apply due to language barriers. Rent-burdened households where English is not the primary language spoken are underrepresented in the state’s rent relief application pool by about 32 percent, according to the National Equity Atlas rental assistance dashboard.

This is one reason why the state program is facing a lawsuit for discrimination against people with disabilities and non-English speakers due to accessibility issues with the application portal. Murillo from the California Office of Housing and Community Development declined to comment on the lawsuit, saying the litigation is still pending, but noted that the state’s program has assisted more than 300,000 low-income households with $3.6 billion in payments to prevent eviction.

“This program was designed to be a temporary support and we stand by the work to date that kept Californians housed during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Murillo said.

San Francisco tries to fill the gap

To provide relief for households who were unable to get assistance from the state program for various reasons, the city is stepping in with its own program.

In response to the state rental assistance program’s closure, the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development reopened San Francisco’s rent relief program on April 1 and has since made $2.6 million in relief payments to 480 of the 3,200 households that have applied. Close to one in three applicants reported taking on shadow debt to pay rent or utility bills, and 27% said they had already received an eviction notice when they submitted their application. While the relief is critical, it is missing legal protections to go along with it, and processing aid requests takes time.

“There’s a whole group of folks who have post-April 1 debt that will never be protected by these laws because they didn’t apply pre-April 1,” Prochovnik said.

The absence of local protections isn’t for lack of trying. State lawmakers on March 31 voided protections unanimously passed by the Board of Supervisors earlier that month. The preemption on local moratoria will remain in effect until next month. So far, no new legislation has been introduced to reinstate a local moratorium.

The city’s eviction defense system, rent relief program and Tenant Right to Counsel program are closely coordinating their services, said Audrey Abadilla, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development. During the eviction process, the programs cross-reference pending assistance from the state program and will intervene with rental assistance not covered by the state program.

The difficulty of trying to avoid eviction

Lara Moon Mertens, 42, faced several complications getting much-needed relief and preventing eviction during the pandemic.

A tattoo artist who lost most of her income during the pandemic as tattoo shops closed down, Moon Mertens was able to make ends meet for some time using unemployment insurance. But when the checks ran out in October, she became unable to pay her rent.

Though her landlord initially cooperated as she submitted the required documents for her application, eventually he grew impatient, she said.

“He kept saying ‘It’s over,’” Moon Mertens said, referencing text messages from her landlord regarding her tenancy. He attempted to evict her in March, but she was able to stop the eviction with the help of Open Door Legal and the legal protections provided by her pending application.

Because the state program does not offer rental assistance for rent due after March, Moon Mertens turned to the Eviction Defense Collaborative for April and May rent. But eventually her state application was denied, and though she is appealing that decision, she is now facing eviction for unpaid rent due in June.

“I had to investigate pretty shrewdly to find out that I was denied in the first place, but also why I was denied,” she said, noting that in previous phone calls with the state program she had been told that her application was in good standing.

Though she said the state program cited inaccuracy in paperwork as the reason for her denial, Moon Mertens suspects that the true reason may be that her unit is zoned as a single residence unit but is being rented out to six different people who all applied for relief.

While she awaits the decision on her appeal and works to fight off the newest eviction case against her, she has signed up for more legal assistance and relief.

“I haven’t been in the best of states,” Moon Mertens said through tears. “But overall, I’m really, really happy to have the resources that San Francisco does, because I know other cities just don’t.”

Eviction, homelessness and equitable recovery

One of the key resources San Francisco tenants do have, according to Melissa Jones, executive director of Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, is the right to counsel in eviction cases. This is one of the important steps that Bay Area counties can take in the wake of the pandemic to stem the tide of evictions.

On the precipice of a wave of displacement, researchers and advocates emphasized the connection between eviction, housing affordability and homelessness, as well as the importance of rethinking approaches to poverty and equity.

It’s so much less expensive for the community and so much less damaging for the individual to prevent an eviction and move into homelessness than to try to move people out of homelessness later.

—Melissa Jones, Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative

“My concern is that we’re going to see out of all this, like pre to the pandemic, we’re going to see much higher rate of homelessness than we ever saw before,” said Thomas of UC Berkeley. “To fix all this, we really need to reshape and rethink how we think about poverty in America, how we think about housing in America and basic necessities in America.” He emphasized what many Bay Area advocates focused on the housing affordability crisis call the three P’s of housing: preservation of existing affordable housing, affordable housing production and tenant protections.

“It’s so much less expensive for the community and so much less damaging for the individual to prevent an eviction and move into homelessness than to try to move people out of homelessness later,” Jones said.

She highlighted the importance of thinking of this moment as a “global recovery moment” wherein we focus on communities that have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s hardships, especially Black residents of the Bay Area.

Data on evictions and rent relief show the pandemic has had disparate impacts on Black tenants. In California, 20% of applicants to the state rental assistance program facing eviction are Black, despite making up only 6.5% of the population.

Prochovnik said that the Eviction Defense Collaborative has historically observed a disproportionate share of requests for assistance regarding evictions from communities of color, tenants with disabilities and elderly tenants compared to city demographics.

For these reasons, Jones encouraged action to support a more strategic, equitable recovery for communities of color than we saw after the 2008 crash and recession.

“There is real opportunity and the resources that are out there,” she said, citing California’s $97 billion budget surplus, the bipartisan infrastructure package and the American Rescue Plan. “It’s up to us to focus, design and plan for an equitable recovery and to learn the lessons from that to start to make standard practices that require it.”