Bay Area planning officials say efforts to encourage dense development will reduce greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles.

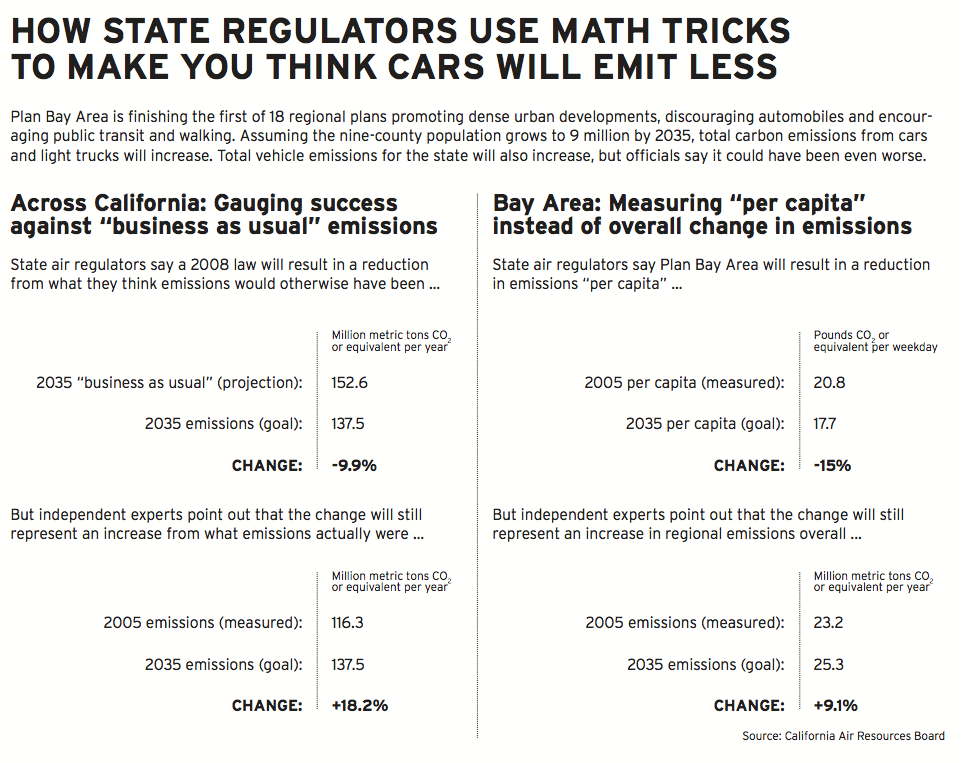

But what they rarely mention publicly is that their goal, a 15 percent per capita reduction of carbon dioxide from cars and light trucks by 2035, actually represents an overall emissions increase.

Essentially, it’s a math trick: The per capita figure hides a predicted regional population growth of 28 percent. That means total passenger vehicle emissions regionwide would actually rise by 9.1 percent — an indication that regional planning is not helping California’s efforts to become a model in combating climate change.

Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg said the decision by state regulators to present greenhouse gas emissions on a per-person basis instead of overall contradicts the spirit of his signature climate bill, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act of 2008.

Steinberg said the law was supposed to help reduce carbon emissions by getting people out of their cars. It requires regional agencies to develop ways to limit suburban sprawl and expand public transit in compact transit villages and the urban centers of San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose.

“The per capita approach is something that we’re going to have to look at,” Steinberg said. “Ultimately the imperative is to improve the climate and reduce greenhouse gases.” But he did say better regional planning would at least slow the growth of emissions and improve quality of life.

Steinberg’s bill was intended to complement Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s vaunted 2006 Global Warming Solutions Act, which calls on the state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all sources to 1990 levels by 2020, and more in future decades.

Plan Bay Area, the first of 18 regional strategies to help local governments implement climate-friendly “smart growth,” or high-density development close to transit lines, will be finalized in July. Ezra Rapport, executive director of the Association of Bay Area Governments, acknowledged that the plan “is not going to reduce emissions” overall.

“But we’re trying to make sure that growth occurs in neighborhoods that have good access to transportation,” he said. “That way we’re part of the solution that reduces greenhouse gas emissions in the future.”

CONSENSUS CALCULATIONS

In settling on the per capita metric, state air-quality officials acknowledged that it would not yield as far-reaching results as they originally hoped for, but that more aggressive goals might not be achievable with current levels of government funding, local zoning laws, existing land ownership patterns and expectations for economic growth.

In May 2009, a 19-member panel of volunteer stakeholders convened a roundtable meeting at the headquarters of the California Environmental Protection Agency in Sacramento to review the rules, as the law required.

At the table were local elected officials and planners, private groups including the powerful pro-industry Bay Area Council, and transportation and environmental organizations including the Natural Resources Defense Council.

After nine months of sometimes heated negotiations, the panel unanimously agreed to let regulators track greenhouse gas reductions from cars and light trucks across California using one of two “relative” measures instead of gauging total annual emissions.

The other relative measure they considered for regional emissions reporting was to assess progress against hypothetical “business as usual” scenarios — what economists think might have happened over the next 20 years without the policy. That measure, also called the “baseline” projection, is what the California Air Resources Board uses most often in public outreach to claim that pollution from vehicles and light trucks will decline.

What they often neglect to say is that total emissions will rise compared with actual, measured emissions. For the state, that means a big difference: comparing the 2035 goal with economists’ business-as-usual estimate, emissions will fall by 9.9 percent. But compared with the actual emissions in 2005, before the climate legislation was passed, emissions will have risen 18.2 percent by 2035.

Yet it is the regional “per capita” figures and statewide comparisons with “business as usual” that get repeated year after year in news stories.

Both methodologies make it hard to measure progress against the total reductions required by the Global Warming Solutions Act, which uses absolute emissions targets.

Allowing emissions to grow in the transportation sector presents a challenge to the state’s overall climate change goals. Other strategies — energy efficiency, alternative fuels, changes in automobile engines and the cap-and-trade carbon market — will have to make steeper cuts to make up the difference.

Dave Clegern, a spokesman for the Air Resources Board who works on climate change issues, acknowledged that despite the per capita reductions, the Sustainable Communities Strategy will not prevent an increase in total carbon emissions from passenger vehicles through 2035.

“In some parts of the state, greenhouse gases will go up, but you have to look at how much they would go up if it were business as usual, without this law,” Clegern said. “Increases might be 18 percent, but it would have been 40 or 50 percent without the program.”

Overall transportation accounts for about 38 percent of statewide emissions, with cars and light trucks making up a smaller slice of the overall pie — 9.5 percent.

Clegern said the possible carbon savings from passenger vehicles represented a small “sliver” of the state’s reduction goals. According to the latest Air Resources Board figures, that would be 5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, out of the total 126 million goal.

He noted that the per capita standard allows each part of the state to use uniform measures of progress. Planners from across the state’s 18 regions are looking to the 166-page Plan Bay Area’s goals and methods to set their own policies.

ECONOMIC PRESSURES

Some environmental advocates who participated in the meetings said that persuading business and government leaders to limit the growth of emissions at all was a step forward. Officials emphasized that regional plans must be re-evaluated every four years, so the metric can be revisited.

“The most important point is that these are real, meaningful targets,” said Amanda Eaken, deputy director of the Sustainable Communities, Energy and Transportation Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “This was the first time that the state has done anything like this. We’re realizing that the greenhouse gas reduction we can achieve is probably greater than we’d originally thought.”

The stakeholders at the 2009 meeting in Sacramento agreed that with state population expected to grow by 12.8 million people between 2005 and 2035, overall emissions would have to grow substantially. The Bay Area alone is expected to grow by 2.1 million, to a total of 9 million.

State air officials said setting absolute carbon reduction targets could deter economic growth. It should be possible to design cities that can still develop while fighting vehicle emissions, said Daniel Sperling, a member of the Air Resources Board and director of the Institute for Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis.

“We decided that the best metric to measure reductions was per capita because it would not penalize growth,” Sperling said. “Emissions are going to be lower than what they’d otherwise be. It’s a starting point that puts the state on the right trajectory to create a policy framework that’s never existed before.”

A final draft of Plan Bay Area was expected to be released in mid-July. A March draft of the plan uses the term “per capita” liberally.

The Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the two agencies leading the process, have published dozens of press releases and newspaper opinion pieces citing the 15 percent per capita goal.

But the popular understanding of the plan seems murky — often the “per capita” caveat gets dropped. In late May, a San Jose Mercury News op-ed by local environmental and civic activists stated incorrectly: “this regional transportation and land-use plan must reduce greenhouse gases 15 percent by 2035.”

UNDER-FUNDED PLANS

Elisa Barbour, a planning doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, said the problem with Plan Bay Area is that the lack of financial incentives for cities makes the policy weak. Each city controls its own development, so incentives must be available for cities to concentrate development in compact, walkable and transit-friendly neighborhoods. And the regional agencies need the authority to mandate standards for things like environmentally friendly zoning laws, she argued.

The 2008 law that set the process in motion, Barbour said, “calls for a more efficient land use and transportation pattern to reduce greenhouse gases. But it’s not clear that the process is actually on track to achieving those goals.”

Plan Bay Area sets aside money for cities to help developers build new housing and jobs near BART, Caltrain and local transit lines.

“The focus of the plan is transportation and land use, so it’s fair to say that it is a very modest bill in terms of climate change,” said Rebecca Long, a legislative analyst at the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

According to the plan, Bay Area cities and counties will receive $800 million in grant funding through 2016 from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Sixty of the region’s 101 cities and all nine counties have applied and are developing 169 “priority development areas,” where growth is supposed to concentrate.

Steve Heminger, executive director of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, said the dissolution of all 400 state redevelopment agencies and recent federal transportation cuts have “crippled” his agency, so there is little money or political power to fully carry out the plan. The agency distributes toll, gas tax and other revenues for transportation projects.

“What the law did was require us to adopt a strategy,” Heminger said. “We’ve done that.”

Steinberg’s office said the 2008 law must be strengthened. Without real teeth, the senator said, the effort to redesign cities to encourage people to drive less could fail.

“Climate change was not only important, it was crucial,” Steinberg said. “We were able to make the transportation and land-use part successful because we had the added element of climate change in the mix.”

Regional planners project that the Bay Area will need 660,000 additional homes and 1.1 million more jobs to support the anticipated population growth.

Kip Lipper, Steinberg’s chief policy adviser for energy, natural resources and the environment, said more important than reducing greenhouse gases in California is developing effective land use planning that actually works.

Steinberg said local governments could do a better job of setting bolder goals. “The work is never done,” he said.

This story is part of a special report on California’s cap-and-trade program, in collaboration with Earth Island Journal and Bay Nature magazine. It was made possible by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Buy a copy of the summer 2013 print edition through the website, or consider becoming a member and get every edition for the next year.