First in a series analyzing the mayoral candidates’ records and pledges on housing and homelessness.

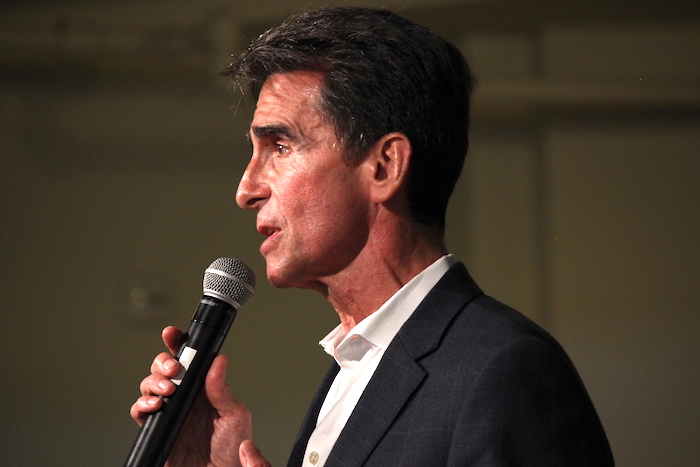

In 2002, Supervisor Mark Leno, a Willie Brown appointee, introduced San Francisco’s first inclusionary-housing ordinance, which requires developers to build below-market-rate apartments or pay a hefty fee.

It passed, 11-0, and Mayor Brown signed it into law. “For-profit developers, nonprofit developers, bicyclists, neighborhood advocates” and others “met in my office every week with the city attorney,” Leno recalled recently. “I took it to the board and it passed.” As a result, a shade under 3,000 below-market-rate units have been built.

A generation ago, mandating developers to fund and build affordable housing was a controversial matter. Now it’s taken for granted and rattled off as one of the key legislative achievements attained by a progressive Board of Supervisors in its decadelong run starting in 2000. But, on a board featuring Matt Gonzalez, Chris Daly, Tom Ammiano and Aaron Peskin, Leno wasn’t seen as a “progressive,” per se. Asked why he carried this legislation, he shrugged and offered his signature smile: “I was attentive to an important issue and ran with it.”

The city Supervisor Leno oversaw had, in his words, “a housing problem.” The city awaiting a potential Mayor Leno has “a housing crisis.” Through the Board of Supervisors and voters, the inclusionary requirements he initiated have jumped from 12 percent to 19 percent. At the same time, the definition of “affordable” has expanded from those earning barely half the area median income to people earning 120 percent of it — or more. (Area median income is nearly $81,000 for a single individual and $115,300 for a family of four.)

Affordable Housing Now ‘for Almost All of Us’

“Fewer than 10 percent of San Franciscans can purchase market-rate housing. Only 15 percent can afford to rent,” Leno said. “This used to be a problem for, quote, unquote, those people. Now those people represent almost all of us. When you talk about affordable housing today, you’re talking about housing for almost all of us.”

As the father of San Francisco inclusionary housing, Leno is proud of his achievement and wants to move it forward. For those who argue this city’s hefty affordability requirements are retarding construction, he can only offer his ever-present smile and a shake of the head.

“If there’s a drop in project applications, from the developers I’ve spoken with it’s not based on another percentage or two” of affordability requirements, Leno contended. “Rather, it’s the cost of labor, the shortage of labor, the escalating cost of land and the fact they are competing with Google and other massive corporations proposing enormous projects who can outbid everybody, every time.”

Leno, in fact, sees greater inclusionary extractions as a way forward; he calls for mandatory higher percentages for developers “building on transit corridors or city-owned parcels.” As such, Leno was dubious of SB 827, the dead-for-now bill penned by his Democratic protégé and successor, Sen. Scott Wiener. “There will be value added with all of this upzoning, so how do we recapture some of that value for the greater public good?” he asked. “But the bigger question is whether a ‘one size fits all’ land-use policy that is this far-reaching makes sense in a state as diverse as California.”

A Pledge to Build More, but Where?

Leno’s mayoral pledge calls for “building dramatically more housing.” But it’s vague about exactly where to do so — and no serous candidate overtly calls for building less or the same amount of housing. Leno desires a Bay Area-wide “comprehensive housing and homelessness bond measure.” But that would be a complex, multijurisdictional matter beyond the immediate control of Leno or any future mayor.

Leno’s most tangible legislative successes — and bitterest defeats — centered on fights to keep renters in their homes. As a novice assemblyman in 2005, he sponsored a bill exempting single-room occupancy hotels from the Ellis Act, which was intended to allow landlords exiting the rental business to empty their buildings.

Leno’s measure passed by one vote, helped by a Republican who had spent time in an SRO hotel as a child. Some 13,500 San Franciscans reside in SRO hotels, and this bill denied a cudgel to owners and speculators wishing to evict them en masse.

Leno’s Ellis Act battle on behalf of the general population has been more quixotic. He was unable to win San Francisco local control over its provisions and could not close loopholes in a law ostensibly intended for aging landlords hoping to retire from the rental business — but, all too often, exploited by bad actors.

Taking Aim at Ellis Act Evictors, Speculators

He pledged that as mayor he would take serial Ellis Act evictors to court. “We are losing too much valuable housing to speculators looking for a quick profit,” he said. But the law allows speculators to do an awful lot. And, as Leno knows well, changing state law is no easy feat.

As a supervisor, assemblyman and senator, Leno created and endorsed measures meant to ease the lives of homeless people. He obtained funding for the city’s first LGBTQ-themed shelter; initiated a mobile methadone treatment facility; did away with the $200 fee for GEDs for homeless young people; and created permanent funding for homeless winter shelters in San Francisco. By removing SROs from the purview of the Ellis Act, he potentially helped prevent thousands of people from becoming homeless.

But none of these steps resembles the frontal assault Leno has formulated this year and sent to city voters via glossy mailers. “I am committed to ending street homelessness by 2020,” Leno promised to voters.

How does he propose doing this? By housing people in the more than 1,800 unoccupied private SRO units detailed in “No Vacancy for the Homeless,” in the Public Press’ fall 2017 issue about solutions to homelessness. (Leno and his top adviser on homeless matters, former homelessness czar Bevan Dufty, both acknowledged they had read the report, for which Dufty served as a source.)

Market Hampers Quick Fixes

Leno’s plan, which cites 1,500 vacancies, is to move 1,000 homeless residents into these rooms “immediately.” But, as the article noted, these rooms are being kept empty for a variety of reasons, ranging from fire damage to an owner’s desire to boost the value of the building. And this plan would be costly. The city would be bidding against real estate powerhouses, including the emerging industry converting low-income housing to high-end hostels for tech workers. In short, Leno faces obstacles in this plan, and may be forced to re-examine the feasibility of doing anything “immediately.”

“There are market forces that would be working against us,” Leno acknowledged. “But, first, we have to know how many empty SROs there are in the city. We should know. My position would be, ‘let’s get this conversation started.’ Let’s bring the owners of these buildings into City Hall and let’s start addressing what the hurdles are that would keep us from accessing the units. Let’s put some energy into having respectful conversations with the owners of those properties and see where we can get to.”

Dufty, now on the BART board, claimed that the unwillingness of the administration of Ed Lee, the former mayor who died in December, to have such conversations regarding vacant SRO rooms — or to consider a number of the suggestions that found their way into Leno’s homeless plan — was a major reason why he resigned as Lee’s adviser.

Leno said it would cost around $40 million to house 1,000 homeless residents in SRO hotels. He said he asked Jeff Kositsky, the head of the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, “What keeps us from doing this?” His was a short answer: “Funding.”

‘Cascading Savings’ by Filling Vacant SROs

Leno’s plan does not outline specific funding sources, however, beyond the “regional housing and homelessness bond” and a “top-to-bottom audit of dollars spent on homelessness.”

That is not ideal. But, Leno said, moving vulnerable people off the street will create “cascading savings” as police, Public Works employees and others are confronted with fewer crises. Public Works boss Mohammed Nuru budgets $60 million a year to clean streets, Leno noted. (Weeks after his Public Press interview, that figure grew by $17 million, as Mayor Mark Farrell announced a campaign to clear encampments and scrub feces and dirty needles off the streets.)

“But Mohammed is using half of that to clean sidewalks,” Leno continued. “Dirty sidewalks are a symptom of a bigger problem — of 3,500 people who are living where they should not be. As long as they do, Mohammed will keep spending $30 million and going back every week and cleaning them again. And that’s a waste of money.”

Moving a large chunk of the city’s homeless indoors into vacant SROs would spare the city from spending this money, which could be redirected into housing. “We’ll save at the Department of Public Health. We’ll save at San Francisco General. The longer people are on the street, the sicker they get. Police who have to deal with the homeless population can spend more time on auto break-ins and home burglaries.” This is what Leno means by “cascading savings.”

Even with that, however, Leno predicted more money would be needed. “Again, if this is our priority, if this is our biggest issue, let’s commit to it,” he said. “Let’s get very serious about it, identify the need, identify the cost, and then determine the revenue to pay for it.”

Correction: This article initially misidentified which mayor signed the inclusionary-housing ordinance. It was Willie Brown, not his successor, Gavin Newsom.