Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.

If San Francisco were able to do the same thing it did 35 years ago to address out-of-control rent increases, the residents of as many as 50,000 apartments would be spared the ravages of the current environment of housing hyperinflation.

But whether updating rent control to apply to all buildings constructed after 1979 would make the city more affordable for the most economically vulnerable is a matter of debate.

In fact, few took notice as the 35th anniversary of rent control in San Francisco came and went in June.

Even the most ardent supporters of rent control, an emergency reform imposed when Dianne Feinstein was mayor, now say they only aim to protect or in some cases reduce the current rent-controlled stock.

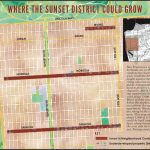

Putting more San Franciscans under the Rent Board’s pricing and eviction protections would serve as a powerful tool to halt the displacement of incumbent tenants harmed by the booming rental market. But the path to expansion would face legal and political roadblocks.

San Francisco could do little to expand rent control without first amending state law. Any conversation about changing the system is stymied by the 1995 Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act — advocated by the real estate industry — which prohibits cities from expanding rent control.

For decades, the industry has squelched any attempts to weaken the state law. However, the clamor in San Francisco to slow displacement nearly succeeded in amending the state Ellis Act this spring. So things could change.

Harry Britt, who presided over the Board of Supervisors when it approved rent control in 1979, said San Francisco’s current housing crisis eclipses the one that spurred the city to freeze rents, and then, over time, tinker with the allowable rate of increase.

“It’s worse,” he said, “Oh, it’s much worse.”

But despite the similarities, updating rent control to buildings built through 2014 would have a weaker effect because rents are already sky-high across the city, Britt said.

Critics, including most mainstream economists, call rent control a “blunt instrument” that ends up distorting the market. Their main arguments: It forces landlords to make up the difference by charging more on non-rent-controlled units; it motivates owners to set move-in prices artificially high; and it discriminates against prospective tenants who plan to settle down and accrue tenure.

Michael Tietz, a professor emeritus of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley, said rent control is “a solution for individuals, but it is not a market solution that works that well” because of the many side effects.

Yet while many detractors dredge up images of retired bankers paying $300 for a Pacific Heights flat occupied since the 1960s, Tietz, who published an influential book on the subject in 1998, said inequities “mostly go the right way.”

“What we found in New York and Los Angeles is that you have a lot of benefit flowing to older people,” he said. “Some of them are doing quite well with savings and Social Security, but many of them are living on the margins.”

Astronomical Increases

Of course, in San Francisco, the rent goes back up to market rate the moment the current resident vacates. So for newcomers or anyone wanting or needing to move, it is a bad time to find a place to live. In the past year, rental prices rose an average of 15.6 percent on apartments that were already some of the most expensive in the country, according to the real estate website Trulia.

As long as they stay put, residents of San Francisco’s 171,000 rent-controlled units — about three-quarters of the total rental housing stock — are protected. Their rents are tied to the regionally adjusted Consumer Price Index, setting the current maximum annual increase to just 1 percent.

Changes in rent, adjusted for inflation, for an average rental unit leased in 2005. This assumes the same starting price for rent-controlled and market-rate apartments, with rent-controlled units receiving the maximum annual price increase allowed by the Rent Board.

SOURCES: S.F. Rent Board, Association of Bay Area Governments, American Community Survey 2005–2012

But this stock has progressively shrunk as units have been either deregulated or taken off the market by owner move-ins, Ellis Act evictions and building demolitions. According to the San Francisco Rent Board, the city has lost about 10,000 rent-controlled units since 2005.

That leaves a quarter of the city’s rental stock open to pricing that in the current hot market can result in large monthly increases that are unsustainable for many tenants.

Any other unit built after June 13, 1979 — the advent of rent control — is also exempted because of the ordinance’s prohibition on regulating new construction.

Battle Lines Remain

San Francisco District 11 Supervisor John Avalos said that in concept he would support another citywide expansion of rent control, but he would take it a step further, to “all rental units in the future as well.”

“It makes no sense to apply it to a particular year,” he said. “We should make it across the board.”

But such an expansion would be no panacea for today’s housing crisis, said Charley Goss, government and community affairs manager at the San Francisco Apartment Association. He said the past 35 years have shown that rent control actually drives up housing costs.

“Rent control creates an incentive for tenants to stay,” Goss said, so an apartment houses fewer tenants over time. If all existing apartments became rent controlled, the city would have to produce even more new housing to make up for the low turnover.

Developers might also be less inclined to build that new housing if the city expanded rent control a second time, said Henry Karnilowicz, former president of the Small Property Owners of San Francisco Institute. Uncertain whether they could make a profit, developers would hold back on new construction.

Tietz disagreed: “At least for a while, there might be a diminution in the rate of construction of new rental housing, but I would expect that to go away as memories fade and builders start collecting new rents.”

Dean Preston, executive director of the statewide nonprofit advocacy group Tenants Together, said other rental regulations had little deterrent effect on future development. He cited the city’s “inclusionary” affordable housing program, requiring developers to set aside some lower-income units.

Winners and Losers

But Goss and Karnilowicz said rent control disproportionately hurts small-property owners, who make up for lost profits by charging new tenants much higher market rates.

“One of the Achilles’ heels of rent control is the imprecision of its benefits,” said Larry Rosenthal, a professor of Public Policy at Berkeley who studies housing. Millionaires are just as entitled to the benefits of the price controls as those living in poverty. That, said Rosenthal “is an abomination.”

While many academics acknowledged that price-regulated tenants would at least be better off in the short term, for the most part, the benefits do not outweigh the costs.

“If you were to bring more units under rent control, the sitting tenants, they would benefit. And who would bear the cost? The owners,” said Edgar O. Olsen, a professor of Economics and Public Policy at University of Virginia. He said rent control’s imprecise subsidies could be replaced by a more robust system of housing vouchers and incentives that spread the costs of lower rents over a wider swath of the public.

Chris Carlsson, a local writer and historian with an activist bent, defended rent control: “I agree that rent control is a Band-Aid. But when you’re bleeding profusely, then you need a Band-Aid.”

Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.