Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco, launched in the summer 2014 print edition. A version of this story appeared in the fall 2014 edition.

For nearly four decades, residents of the western half of San Francisco have succeeded in blocking any local zoning changes, saying that adding higher-density and affordable housing options would harm the neighborhoods’ residential character.

But as rental prices skyrocket, the city could add thousands of new apartments without increasing parking problems by carefully tweaking housing regulations in the west — an area largely untouched by the recent construction boom.

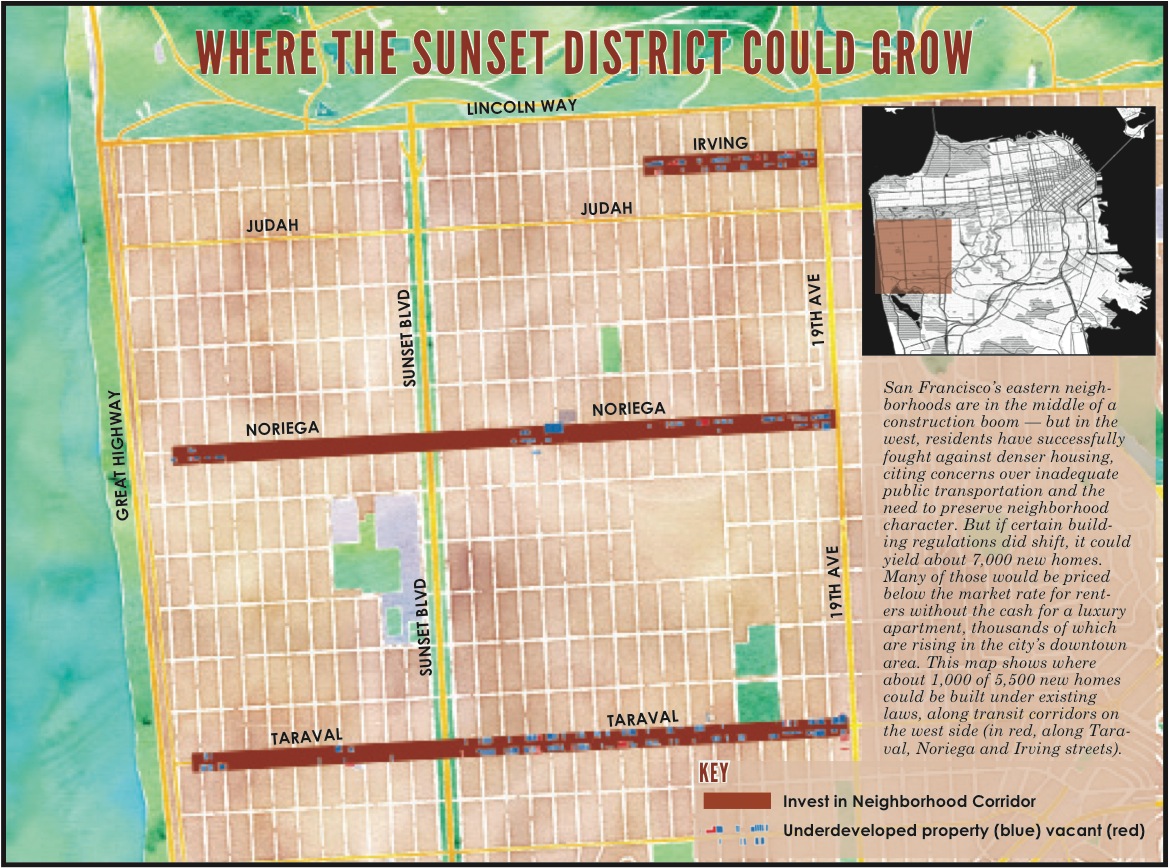

Joshua Switzky, the acting director of the citywide planning division of the San Francisco Planning Department, said that rezoning along a few key transit corridors in the Sunset and Richmond neighborhoods could add roughly 7,000 new apartment units. To do this, a few key commercial streets served by public transportation would need to be rezoned to increase the housing density by 25 to 30 percent. He emphasized that these estimates are based on his planning experience and not on any formal analysis.

Even under existing building height and density limits, the west side could fit approximately 5,500 additional housing units near Muni lines and retail districts, Switzky said. This estimate excludes the planned developments around Parkmerced and San Francisco State University.

If the Planning Department rezoned the west side to remove existing density limits, developers could build four or five units per lot, instead of the current limit of three. That would require changing some areas from the Neighborhood Commercial District designation to, for example, Neighborhood Commercial Transit District.

But in a part of the city that is ferociously against changes that would bring newcomers or exacerbate parking shortages, rezoning is easier said than done.

The last time a city official proposed denser residential development along busy transit corridors, the idea was nixed.

Amit Ghosh, then the city’s chief planner, drafted a citywide plan for the 2004 Housing Element that would have increased density and removed parking along many major commercial strips well served by public transit.

The backlash was overwhelming.

Neighborhood groups threatened legal action, and then-mayoral candidate Gavin Newsom promised to replace the leadership at the Planning Department and rewrite the whole plan. Opponents said the city should have performed an environmental impact report and sought their participation.

It became clear that before city planners could even contemplate altering the west side, they would need widespread support from the people who lived there.

Rezoning the western neighborhoods would require dramatically improving transit, city officials and neighbors say. That requires analysis of each corridor in a cohesive western neighborhoods area plan that addresses concerns about neighborhood character and displacement because of rapidly rising rents and evictions in the neighborhood.

AnMarie Rodgers, a senior policy adviser at the Planning Department, said the Market and Octavia plan in the Western Addition succeeded in increasing density and height limits because the old zoning no longer fit the neighborhood. Community involvement produced changes that “basically kept the neighborhood the same,” she said.

“When we talk about changing the character of a neighborhood, we have to talk about how the change will serve those who live there,” Rodgers wrote in an email.

(Rodgers presented her thoughts on western neighborhood rezoning at Hack the Housing Crisis, a one-day conference in June organized by the San Francisco Public Press, Shareable and the Impact Hub Bay Area.)

One massive project has only just overcome years of neighorhood push-back. In 2011, the Board of Supervisors approved plans to build almost 5,700 new housing units in the Parkmerced neighborhood, but residents opposed it out of concern that it would displace existing tenants and sully the area’s historic character. This August, the First District Court of Appeals gave the 20-year project the green light, and construction could begin by next fall, the San Francisco Business Times reported.

Charges of NIMBYism

The Sunset and Richmond districts have resisted change more than many other areas of San Francisco. Zoning in the eastern neighborhoods, by contrast, has changed two or three times in the last 15 years.

C. William Domhoff, a sociologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, wrote that local groups across San Francisco started to have success opposing growth efforts since 1965, when Western Addition activists stopped the city from building a highway across the neighborhood.

Then in 1972, 47 neighborhood groups formed the Coalition for San Francisco Neighborhoods after the Planning Department rejected their appeals to reduce allowable building height and bulk. Four years later, the mayor reached out to these groups to include them in decision-making.

In 1996, Proposition G reinstated district-by-district elections for the Board of Supervisors leading activists and neighborhood groups to shape the board’s composition in 2000.

Paavo Monkkonen, an assistant professor of urban affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles, said efforts to keep out newcomers, especially renters, are economically motivated.

“Cities want to keep prices high because homeowners are the people who vote, and they want their houses to be expensive, and that’s their big asset,” Monkkonen said.

William Fischel, an economist at Dartmouth College, called this the “home-voter hypothesis.” He said that in most cities, homeowners are the most active slice of the electorate.

“It is the most concealed motivation around,” Fischel said. “It’s gauche for people to get up and say at a public meeting, ‘My home value is going to go down if they build apartments across the street.’ They’ll talk about the effects of traffic and noise, good schools.” Economists say this can affect the value of homes, he said.

While new development does not necessarily harm real estate values, neighbors oppose these plans because of the chance that it might, Fischel said. Restricting housing supply tends to prop up home resale prices.

But western neighbors have valid reasons to oppose rezoning, said Mary Gallagher, San Francisco’s former assistant director of planning. Increasing housing in low-density areas leads to the nuisance of construction and demolition, residential and business displacement, traffic congestion, parking problems and a change in the character of the neighborhood. This would all come in exchange for a modest number of affordable housing units.

Displacement Worries

Displacement of long-term renters is a big concern in the western neighborhoods, which have large middle-income populations. But recent census data show a rapidly shrinking middle class.

Hiroshi Fukuda, land use and housing chair of the Coalition for San Francisco Neighborhoods, said that if large-scale development produced mostly market-rate apartments, it could displace established residents paying lower rents.

Developers are required to set aside only 12 percent of new housing units affordable for low- and moderate-income households through the city’s Inclusionary Housing Program.

So while many of these residents cannot afford market-rate housing, they also do not qualify for low-income housing. Yet San Francisco has built or entitled only about 27.5 percent of the moderate-income housing it needs, compared with 56.8 percent of low-income housing, according to the Planning Department’s first-quarter 2014 pipeline report.

Meanwhile, it is getting harder for average residents to buy homes. Only 14 percent of for-sale homes are affordable to the middle class, real estate website Trulia reported in May 2014.

Gallagher said rezoning might not be the most straightforward solution to the housing shortage. In an area zoned primarily for buildings of one-to-three units, a corridor of high-rises would degrade the small-scale feel and walkability of the neighborhood.

To complicate things, one estimate puts the number of vacant apartments citywide at about 10,000 homes. KALW News reported that landlords keep them empty because they want to avoid combative tenants, or they cannot charge high enough rent because of the limitations of rent control laws.

“New units being built does not mean they will be lived in,” said Rose Hillson, a Coalition for San Francisco Neighborhoods activist. “The cycle of needing more housing will perpetuate. The city will never be able to build itself out of the affordable housing crisis.”

Changing Political Climate

Some within the San Francisco Neighborhoods Coalition say they are open to allowing growth within current zoning limits. Affordability for middle-income residents, not “densification,” is their biggest concern.

“They’re building the wrong type of housing for people who don’t even live here,” Fukuda said.

According to a survey by Civinomics, a startup public policy research company, 40 percent of polled western neighborhood residents said they “strongly support” or “somewhat support” rezoning of their block for higher density.

“For someone who’s not a native, my wife and I chose deliberately to raise our children in the city, so I don’t want a suburban existence,” said Ike Kwon, who bought a home when he moved to the Sunset District with his family six years ago. “A city is rich when it’s very diverse. You want to be in a dense area. Otherwise, go somewhere else.”

District 4 Supervisor Katy Tang supports additional development up to the existing 40-foot height limit. She recently published a Sunset District Blueprint in consultation with community groups, developers and the Planning Department. Most of this new housing would be built above retail space, in the transit and commercial corridors.

The city has already targeted many of these corridors for business district improvements. The Invest in Neighborhoods Initiative aims to distribute resources from city agencies and nonprofit groups to boost commercial growth.

Increased density would provide more customers for older commercial corridors, and a report from SPUR, a local urban policy research organization, said mixed-use projects with housing above retail could improve the streetscape, add new public spaces and enhance shopping choices.

A more robust retail corridor could also reduce automobile trips, said Tom Radulovich, a member of the BART board of directors and the executive director of Livable Cities.

Western Neighborhoods Planning

While city planners have crafted neighborhoodwide construction plans for other areas of the city, they have never extended that to the west — even though doing so could facilitate housing construction.

Developers must submit environmental impact reports for large projects, which can then become mired in red tape. But a western neighborhoods plan could assess the impacts of multiple projects at once, unifying them under a single comprehensive impact report and exempting each developer from filing independently.

That would speed up the construction process. It would also enable city staff to address community concerns and plan new affordable housing at the neighborhood level, instead of a project-by-project basis.

It would save “tons of time and money,” Switzky said, adding that areas that use combined environmental impact reports “get through the process a lot faster and with a lot more certainty.”

And the west’s geography is inherently unattractive to developers who would prefer to build on a large scale. Compared with the available land in the city’s southeast sectors, western parcels are tiny. A developer might want to buy one if it could be combined with an adjacent parcel, but that process is difficult, Switzky said.

One option is to allow planned-unit developments, an approach that relaxes guidelines for smaller parcels. SPUR and the San Francisco Housing Action Coalition have endorsed this idea. It would require developers to include more below-market-rate housing than that under current inclusionary housing rules. The Eastern Neighborhoods Program requires 15 percent of new apartments in large buildings to be set aside as affordable, as opposed to the citywide mandate of 12 percent.

While developers would clearly benefit, homeowners outside rezoned corridors are a different story.

“If you rezone selectively around the transit areas, then the properties of the owners around where you rezone are going to make a lot of money,” Monkkonen said. “But everyone else doesn’t make any money off it and bear the cost of having more transit.”

Monkkonen said that one way to help out homeowners would be to redistribute some of the higher property taxes in the rezoned areas by reducing the tax burden on properties on side streets.

“It’s really hard, especially in neighborhoods that are like the western neighborhoods, to drive down the price of housing to make it more affordable by building more,” said Robert Hickey, a senior research associate at the National Housing Conference and the Center for Housing Policy, who wrote a report on “upzoning” for affordable housing.

And a plan could allay displacement concerns as well. At the Public Press’ public event in June that focused on housing solutions, Hack the Housing Crisis, Rodgers from the Planning Department proposed rezoning the western neighborhoods for higher density on the condition that current residents would get to live on-site.

Transportation Problems

Because cars are so essential to western neighborhood residents, it would be politically unpopular to increase housing density by dropping parking requirements in new housing.

That could explain why one modest zoning change, which Switzky described, has not happened yet: eliminating all parking requirements for new developments. That would force new residents with cars to find street parking, a precious commodity in the city, potentially threatening its availability. About 93 percent of the Outer Sunset’s parking spaces are unmetered street parking, a higher percentage than in any other neighborhood, according to the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency’s Parking Census, published in May.

Housing construction is booming in San Francisco’s eastern neighborhoods, where a robust public transit system has allowed walkable neighborhoods to absorb waves of new residents.

But the nature of the western suburbs makes it hard for experts to envision new housing without also bolstering public transportation.

Sparse and infrequent buses mean that trips downtown can take a long time. Right now, residents in these neighborhoods depend on their cars. In the Outer Sunset, 63 percent of adults drive to work, many more than the city average of 46 percent, according to a 2011 San Francisco Neighborhoods Socio-Economic Profiles report.

For years, the city has been promoting its Transit Effectiveness Project, which includes a bus rapid-transit system, featuring dedicated transit lanes and other infrastructure innovations on Geary Boulevard. But in expectation of that expensive project, the city has shelved other, smaller fixes to the system, Radulovich said.

“Just tuning up the service, getting things running faster is something that they could have done years ago,” he said.

Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco, launched in the summer 2014 print edition. A version of this story appeared in the fall 2014 edition.

CORRECTION 11/18/14: Due to an editing error, the caption on the map in the print edition incorrectly stated the number of possible new units that could be built in the Sunset District. The number is 1,000, not 5,500, which applies to a larger area on the city’s west side.