Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.

In Seattle, developers are racing to build what has become a wildly popular new type of apartment complex: “congregate housing.” Miniature studios averaging 150 square feet are so tightly packed that foldaway beds must be stowed during the day. Instead of an eat-in kitchen, residents can sometimes share cooking space with 30 other people down the hall.

Could what developers are calling “co-living for the middle class” help keep down San Francisco housing costs? If Seattle’s experiment is any measure, it might bring thousands of basic housing units priced below $1,000 per month, aimed at young single people who might not miss the extra elbowroom.

San Francisco has not exactly embraced the idea. In 2012, Supervisor Scott Wiener proposed allowing the minimum area of an apartment to go below 220 square feet. But after objections from neighborhood activists, concerned that profiteers would take advantage of the overheated rental market, allowed a maximum of 375 to be built citywide.

Two years later, Patrick Kennedy of developer Panoramic Interests, floated the idea. He is the first one to begin building micro-apartments. He is halfway through construction of 120 units at 1321 Mission St., and expects to start leasing in a year.

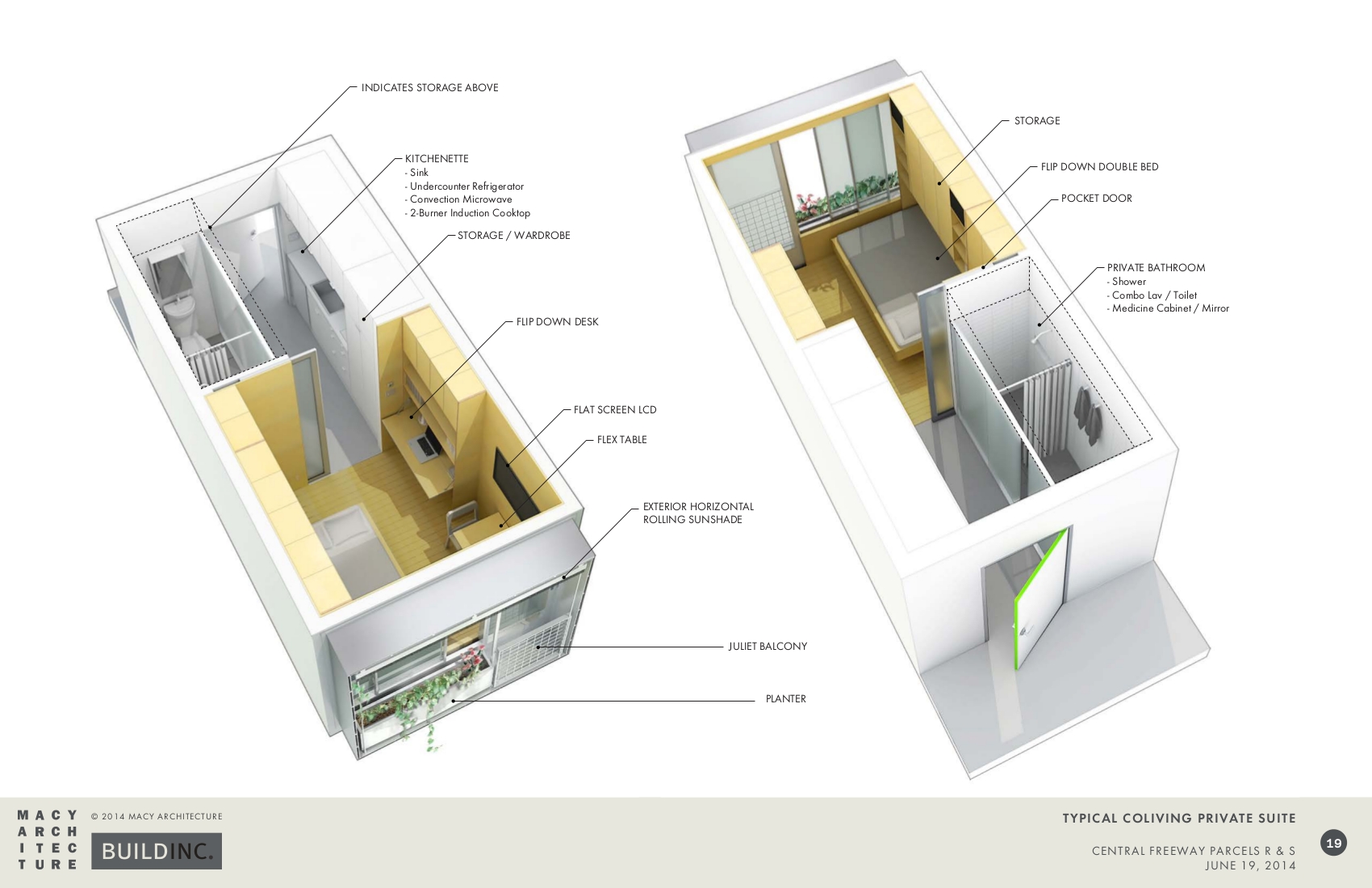

Congregate housing would fall under the same tiny-apartment cap. But its design is different, with expansive lounges and other shared spaces, creating the feel of college dorms for grown-ups.

Only one current San Francisco project resembles Seattle’s congregate housing. Local developer Build Inc. will fit a total of 34 tiny units on a lot that is 120 feet long and 23 feet wide along Octavia Boulevard in Hayes Valley, pending approval from the city. Every tenant will get a bicycle parking space in the basement. The top floor will be shared kitchen and dining space, and the roof will have a communal garden.

Developers in San Francisco say that policymakers might release a wave of creative residential design by lifting the 375 cap. Because the city issues these permits on a first-come, first-served basis, landowners are hesitant to pay for architectural designs for a project if another developer gets approved first, said Amanda Loper, a senior associate at David Baker Architects.

Efficiency and Profits

In the last three years, Seattle has built about 900 of the pocket-size dwellings and thousands more are on the drawing board.

Though they are market-rate, congregate apartments can be cheaper than conventional housing, typically renting for $700 to $1,000 per month, utilities included, said Scott Shapiro, managing director of Seattle housing developer Eagle Rock Ventures.

That can look attractive in overheated rental markets. In May a one-bedroom Seattle apartment cost about $1,455 excluding utilities, according the Seattle Times.

The real estate markets in Seattle and San Francisco are similar. Almost every plot of land has something on it, creating fierce competition. And most land is zoned for single-family homes or other low-density structures, making it off limits for efficiently packed residential buildings.

“There is basically no vacant land” in Seattle, Shapiro said. “We have to tear down something else to build.”

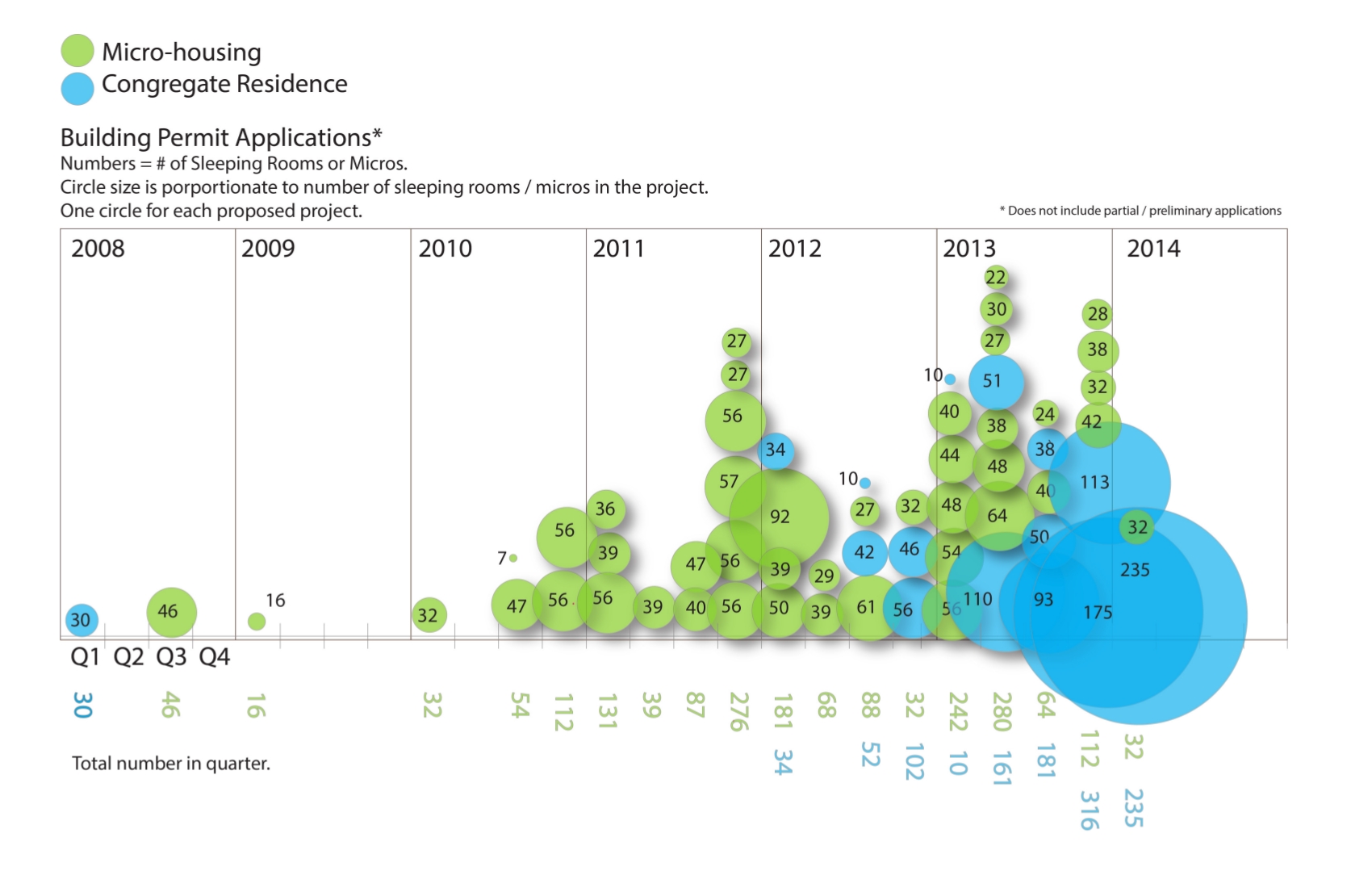

In 2010, developers there responded to that scarcity by building droves of micro-apartments, a precursor to congregate housing, to maximize the number of renters in each building. In Seattle, these apartments maxed out at 285 square feet.

The design took off in 2011, when developers applied to build 533 micro units.

But from mid-2013 to early 2014, most applications — 732 of them — were for the even tinier congregate apartments.

Young and Single

The target consumer for congregate housing is a young professional who spends most of the time out of the house. “The majority is Gen-Y millennials, a lot of people in transition, going to Seattle for a job, or in school or just got out of school,” Shapiro said. “They want something safe, clean, affordable and well-located.” How do you know congregate housing is a good fit? “You’re never home — unless you sleep,” he said.

This demographic is increasingly common in San Francisco, where census data show that 39 percent of the population lives alone. Almost three-quarters of household heads aged 25 to 44 earn at least $60,000 annually, putting congregate apartments within their price range.

San Francisco’s housing market is complex, Kennedy warned. Almost all residential construction is concentrated in the dense eastern half. While its abundance of workplaces, shopping, entertainment and mass transit make it prime territory for building micro-apartments, or even-denser congregate housing, it is “also ideal for high-end condos and for new offices,” he said.

But while luxury housing is currently much easier to build, Kennedy said he is optimistic that the future of San Francisco housing is small-scale.

Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.