Among the companies benefiting were two Sacramento strip clubs and some of the nation’s largest corporations, including Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, Yum! Brands, FedEx, Starbucks and Wells Fargo

Large businesses in California “enterprise zones” reaped billions of dollars in tax breaks in recent years, but tax privacy laws made it impossible to tell whether the program actually encouraged companies to hire new workers in economically disadvantaged parts of the state.

So over the summer, the Legislature overhauled the $750 million program, which Gov. Jerry Brown derided as “wasteful” and “inefficient.” Instead of killing the program outright, though, the state put aside an equivalent amount for an even more elaborate array of tax credits.

While San Francisco officials said that a local, parallel tax break program will continue, businesses across the state are now trying to figure out how to change their hiring practices to recapture some tax benefits as the December 2013 sunset approaches for the statewide enterprise zones.

Tax consultants and business groups are complaining that the new credits will upset a program that helped hundreds of thousands of disadvantaged workers, and will create hurdles for businesses that want to add jobs. Some repeat the criticism leveled against the old system: that it favored big businesses over small ones.

Enterprise zones started in 1985 as a modest effort to help a handful of underdeveloped neighborhoods by providing hiring incentives for businesses. Back then it offset state tax revenue by just $675,000.

But the cost to taxpayers soared as many more businesses discovered they were eligible, even ones located in areas that were in no way economically depressed.

Three years ago the state credits shot past $700 million annually, according to an analysis by the California Budget Project, an independent think tank in Sacramento. All told, the state spent $4.8 billion on the program.

One of the biggest problems was that the identities of the companies benefiting were secret due to tax privacy laws. When legislators restructured the program, they made the names of new participating businesses public — though the disclosure will not be retroactive.

Among the fiercest critics of enterprise zones was the California Labor Federation, a union advocacy organization, which launched a reform campaign that called the tax break a “corporate gravy train.”

Steve Smith, a spokesman for the labor group, said the program grew rapidly in the middle of the last decade, when tax consulting firms discovered they could help companies get credits for hiring workers under a wide range of financial and geographic circumstances.

By 2013, he said, about two-thirds of the credits went “to corporations that make billions of dollars and are getting tax credit for existing jobs instead of making new jobs.”

In a study released in June, the California Budget Project found that businesses with assets of $1 million or more claimed 70 percent of all enterprise zone dollars.

Opponents in the Assembly said the program strayed from its original purpose: to encourage employers to hire disadvantaged workers in economically depressed communities. Instead, they said, it became a giveaway to big businesses for jobs that would have existed regardless.

LOCAL ZONE UNCHANGED

Political hostility to enterprise zones reached a tipping point in May when journalists discovered that among the companies benefiting were two Sacramento strip clubs and some of the nation’s largest corporations, including Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, Yum! Brands, FedEx, Starbucks and Wells Fargo.

The names were disclosed because a few cities decided to honor a public records request by KCRA-TV, a Sacramento television station. For the most part, only state tax officials know what companies got the tax breaks. Citing privacy concerns, the Franchise Tax Board for years refused to identify the companies.

But a memo from the Department of Housing and Community Development to the city of Santa Clarita argues that local governments are free to release information about enterprise zone applications at their discretion.

The San Francisco Treasurer’s Office declined to release the names of local participating businesses to the San Francisco Public Press. But the office did provide an annual financial summary from the 2010 tax year. The state tax enterprise zone tax savings for San Francisco businesses was $37.8 million, the report shows.

San Francisco also passed a complementary local enterprise zone program in 1992. Data from the Treasurer’s Office shows that 63 companies received the local tax break by claiming payroll tax exclusions for 287 employees. That added up to a total local 2010 payroll tax savings of $220,000.

The San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development says it plans to continue to offer a local tax break equivalent to 1.5 percent of workers’ salaries. That will remain unchanged even as the city moves away from payroll taxes toward a gross receipts tax in 2014.

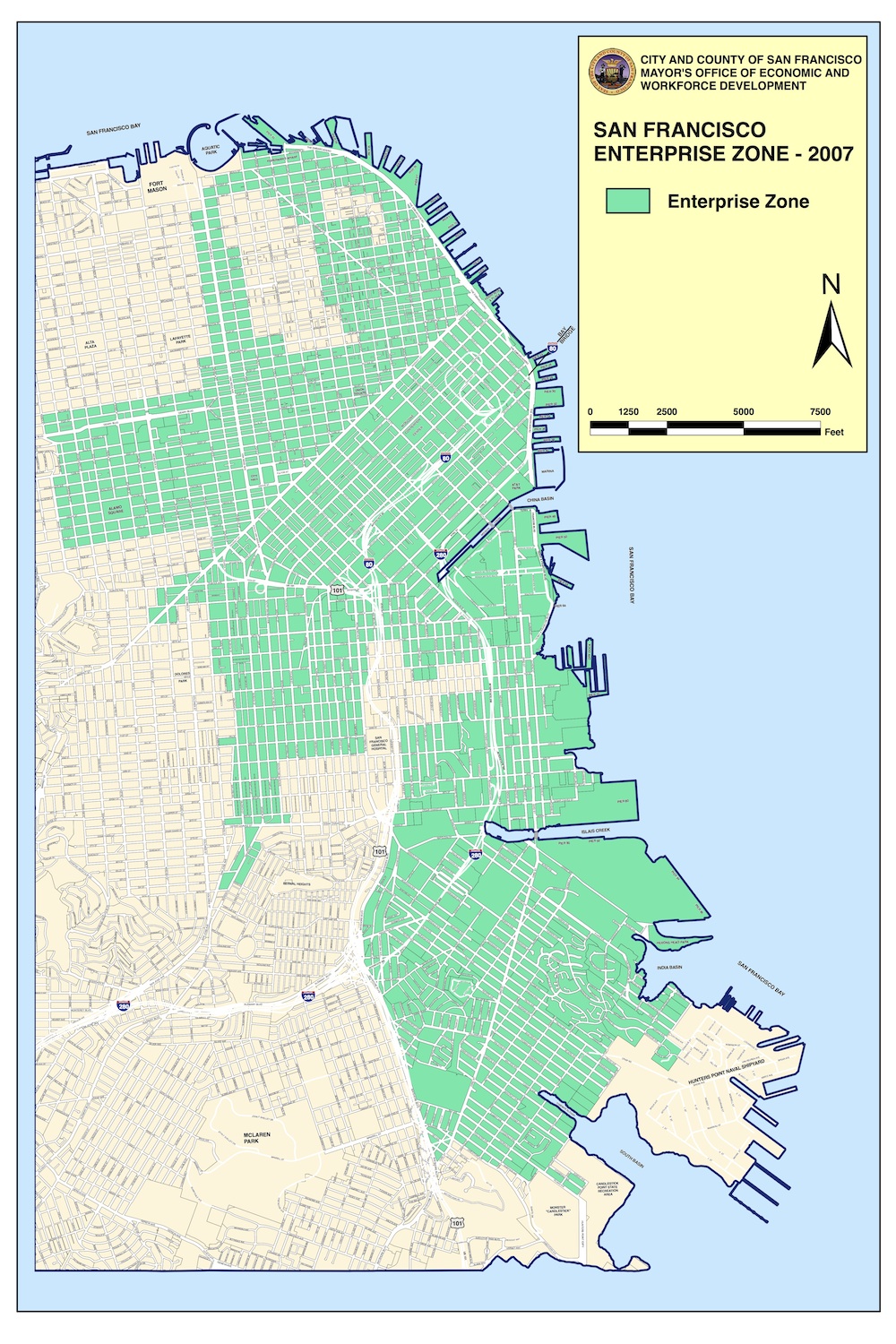

San Francisco’s program is geographically identical to the old state zone. City officials maintain that these areas need development help because they are economically distressed.

But the zone, one of 42 in the state, was expanded in 2007 to include almost the entire eastern half of the city, and includes some prosperous residential and business areas, along with low-income ones. The zone encompasses the Financial District, SoMa, North Beach, Civic Center, Chinatown, the Western Addition, parts of the Mission, Dogpatch and Bayview.

STATE SHAKES UP RULES

The enterprise zone program is being replaced with three new credits. Together they will cost up to $700 million. Supporters say these programs will create jobs more efficiently than did the old enterprise zones.

The new program allows for up to $400 million a year for equipment tax credits in the manufacturing and biotech sectors, $100 million in incentives for businesses to relocate to California and at least $200 million in incentives for hiring disadvantaged workers.

For the hiring credits, one important change is that companies must prove a net increase in jobs.

Previously, most companies located in enterprise zones got tax breaks by hiring “disadvantaged” workers — the chronically unemployed, ex-offenders, veterans and recipients of federal or state economic assistance.

Under the new hiring credits, companies can still claim credits if they are in the former enterprise zones (except the wealthiest areas), in census tracts with the highest rates of poverty or unemployment, or on former military bases.

The old system started with a $36,000 credit per employee, an amount that fell in subsequent years. That meant companies that replaced workers frequently could claim bigger tax benefits. The new tax breaks increase that amount to $56,000, and hold steady over a worker’s first five years, creating an incentive to retain staff.

Smith said the new plan, proposed by the governor, “taps into the strengths of California as an innovative economy and what it economically has to offer.”

But an industry group set up to advocate for the enterprise zone system says the cure will be worse than the disease.

“We know the program wasn’t perfect, and we never objected to conversations of change,” said Craig Johnson, president of the California Association of Enterprise Zones. But the old program achieved its goals, he said: “The beauty of enterprise zones is that they are proven job creators in poor neighborhoods.”

The old law allowed credits based on wages up to $12 per hour. Under the new law, employees must make between $12 and $28 per hour.

Robert Salazar, president of the Alliance Group, a Los Angeles-based tax advisory firm specializing in federal and state tax credits, said the problem with the reform is that businesses that hire those qualified employees tend to be small- and medium-sized and won’t meet the wage requirements.

Qualifying for the new credits could be costly because companies usually rely on tax advisory companies to apply for them. Proving a net increase of jobs is the hardest part. It is a time-consuming process.

“It’s almost impossible for a small business to take advantage of the new tax break,” Salazar said. “Small businesses just don’t have enough resources.”

Max Schenker, vice president of the Los Angeles-based Tax Credit Company, said the number of different kinds of tax breaks for companies that previously claimed them will be “drastically smaller” under the new rules, and many of the companies claiming large tax credits will lose that money at the start of the new year.

Johnson said an unpublished report from the California Enterprise Zones Association surveyed 15 state enterprise zones and found that fewer than 1 percent of 2012 applications by companies would qualify for the credit under the new, more restrictive requirements. Johnson said the change would seriously harm those businesses that counted on the tax break for the upcoming years.

Money previously saved through the enterprise zone program “to hire more employees, or grow their businesses,” Johnson said, “will now go to paying higher state tax bills.”

Brown’s proposal passed the Assembly quickly in late June — within 72 hours of its introduction. Most of the support came from Democrats, who gave it 54 votes, the minimum required to meet the two-thirds voting threshold for tax law changes. The Senate passed the bill in June by a 30-to-9 vote.

The speed with which the law passed made tax advisory consultants’ heads spin. David Goss, vice president of GMH Tax Credits in Fresno, said no one in the Legislature understood what the effect of the bill might be. “They just wanted to pass it as soon as possible.”

One of the legislators’ main concerns while crafting the language of the bill was that privacy provisions of state tax law made it impossible to know which companies took advantage of the tax breaks — meaning that the real effect on job creation could never be known. The new law solves that by creating a public database of companies that claim the credit and the number of jobs they create.

This story is part of a special report on workforce development in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the fall 2013 print edition.

Buy a copy of the fall 2013 print edition through the website, or consider becoming a member and get every edition for the next year.