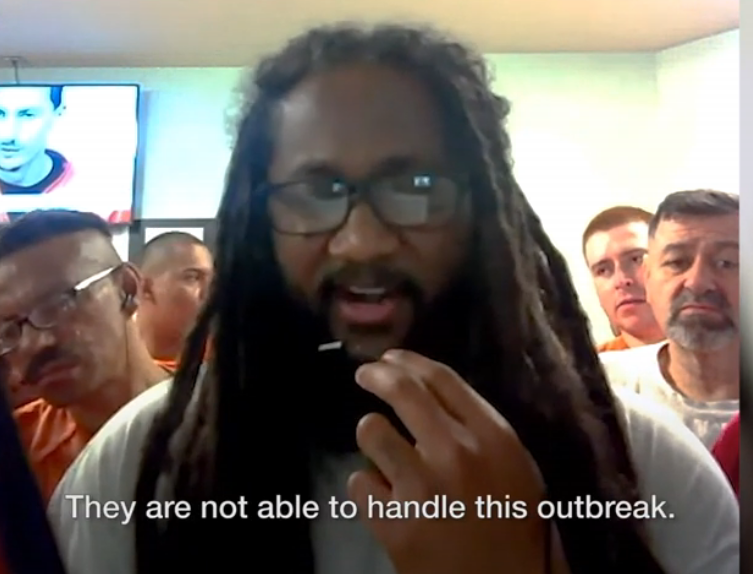

In late March, a cell phone video made by detainees was leaked to the public from Mesa Verde Immigration and Customs Enforcement Processing Center in Bakersfield, Calif. Dozens of men in orange jumpsuits walked past the camera while Charles Joseph read a petition.

“Many of us have underlying medical issues,” he said. “This turns our detention into a death sentence, because this pandemic requires social distancing and that is impossible in this environment. We request that you give us parole or bond so we may return to our families.”

Joseph’s plea caught the attention of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office, which joined a lawsuit with the American Civil Liberties Union, Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, and two law firms — Lakin & Wille, and Cooley LLP — seeking the release of detained immigrants with pre-existing health concerns. As COVID-19 spread across California, lawyers scrambled to get their clients out on bail to reduce their risk of catching the disease in overcrowded prisons.

The office’s three-year-old immigration unit has been especially successful at this. Since the Bay Area shelter-in-place orders were announced in mid-March, the team has played a key role in reducing the population of two major ICE detention centers by about two-thirds.

Two weeks ago those facilities, Mesa Verde and Yuba County Jail, together held just 174 detainees, down from a total of 523 on March 11.

It’s an effort that criminal defense attorneys are attempting to replicate at San Quentin State Prison, which has suffered a severe outbreak of the coronavirus in the past week, with more than 1,100 inmates testing positive for the virus. Securing release for prisoners is a race against time.

Now, lawyers with the immigration unit plan to come to their colleagues’ aid. “The immigration unit is also looking at collaborating with the criminal defense unit to help people get released from prisons because of the COVID outbreak, specifically at San Quentin,” said Carla Gomez, a public defender on the immigration unit.

While criminal defense is a universal right in the United States, immigration defense for ICE detainees is not, and is consequently extremely rare. Many detainees never secure a lawyer and, as a result, agree to charges that could easily be debunked.

Working 24/7 on immigrant bail requests

This makes the Immigration Unit at the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office — founded in 2017, after Donald Trump became president — something of an anomaly. While a 2010 Supreme Court ruling, Padilla vs. Kentucky, requires that lawyers inform their clients about possible deportation impacts of their cases, most public defenders’ offices have one or two staff members to handle this requirement. In San Francisco, there are nine, making it the second largest unit in the country, after New York City.

It’s led by Francisco Ugarte, a longtime immigration attorney who successfully advocated for Joseph’s release. Joseph, 34, is a Fijian immigrant who spent 12 years in prison for robbing a convenience store. Upon release he was immediately picked up by ICE and transferred to Mesa Verde, a for-profit facility that operates under an $1.6 billion ICE contract. Three weeks after the video was leaked, he was granted supervised release by a federal judge, along with three other detainees. Joseph, who suffers from severe asthma, now wears an ankle monitor to track his movements. All four will still have to attend immigration hearings regarding their cases.

In his ruling, Judge Vince Chhabria ordered a review of the center’s detainees who may be eligible for release. The order sparked a new, all-hands-on-deck approach to reduce populations at those two centers in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Attorneys from other units took crash courses in immigration and many worked all hours on bail applications.

The success was almost immediate.

“People started getting out, one by one,” said Deputy Public Defender Jennifer Friedman. “It’s been a Herculean task filing these bail application requests. And for many people, this is the first time detainees have ever had a lawyer willing to look at their case.”

Gomez, who works in the immigration unit, said each bail application takes days — and that she’s been working “24/7” to get people released. “If you want to put together a strong bail application, it takes a minimum of three days,” she said.

New focus on depopulation

Even with an entire unit dedicated to this work, the San Francisco Public Defender’s office has a hefty caseload. The office can take on any case being heard in San Francisco’s Federal Immigration Court, which number in the hundreds each year.

The release of detainees at Mesa Verde and Yuba detention centers is determined by one of the 24 local immigration judges. The two immigration courthouses — one on Sansome Street for detainees, and another on Montgomery Street for non-detained immigrants — are perpetually busy. As of May 2020, both courts had more than 70,000 pending cases to review.

Emi MacLean, a deputy public defender on the immigration unit, joined the team when it first launched. She said the unit’s practice was to send a coalition of lawyers into court a couple of days a month to represent everyone who appeared.

“Any other day folks would go into their hearings alone,” she said. “Some people will accept their deportation, often without understanding what’s happening. People will have lived in the United States for 20, 30, 40 years and would have the right to remain here if they had a lawyer, but they don’t know that. Then they’re sent back to their country of birth by the end of the day.”

The team was effective in getting cases dismissed or people released on bail, but when COVID-19 hit, it became clear to lawyers in the unit that two days a month wouldn’t be enough to empty the detention centers.

“We realized we needed a bigger sword, and way to get people out faster,” Friedman said. “We believe depopulation is the most effective method to reduce the spread of coronavirus. If it was up to us, those detention centers would be emptied and permanently cleared.”

Little testing in ICE detention

Time is of the essence. None of the people still detained at Mesa Verde and Yuba ICE detention centers has been tested for the coronavirus. On June 19, news broke that a medical provider who had been serving the population had tested positive.

“ICE claims they can’t test everyone,” Gomez said. “They don’t want to put in the resources, because they don’t see the detainees as human beings. It’s preposterous. The detainees weren’t even notified about COVID initially.” She said immigration officials “did nothing to change the conditions in the beginning. There wasn’t even soap for everyone.”

ICE said it’s providing adequate care. “One of ICE’s highest priorities is the health and safety of those in our custody,” said agency spokesman Jonathan Moore. “ICE remains fully committed to ensuring that those in our custody reside in a safe, secure, and clean environment, and that our staff and facility adhere strictly to the National Detention Standards.”

“There have been no COVID-19 positive detainees at Mesa Verde ICE Processing Center nor at the Yuba County Jail as of June 26,” he added. But MacLean pointed out there has not been a single test administered to detainees since the outbreak began.

Those who remain detained are keeping the pressure on. Since April, they’ve been organizing sit-ins and hunger strikes, demanding better conditions to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Joseph, who was released on bail, continues to speak out for the people who are still inside.

“We’ve fought this system for days, months and years to be reunited with our loved ones, because our detention for a civil matter may be a death sentence,” Joseph said at an online press conference in April. “This pandemic has caused us not to be quiet anymore.”