Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.

Two Bay Area designers are re-imagining the home as a simple consumer good. If they and other entrepreneurs are successful, San Francisco’s marginal land — including parking spaces — could theoretically be retrofitted to accommodate hundreds or thousands of these barebones, movable living spaces.

Tim McCormick and Luke Iseman have devised similar concepts for “productizing” modest but modern homes that consumers could order online or even build themselves. Both use inexpensive materials that can be assembled offsite as an alternative to conventional construction practices, which they call unnecessarily complicated, time-consuming and costly.

“Right now, housing is like the furthest possible thing from a product,” said McCormick, a product developer and writer based in Palo Alto. “It’s completely unique in every single case, with infinite layers of professional specialized labor.”

The cost of all that professional specialized labor adds up. Mark Hogan, a San Francisco-based architect, estimated that the cost of building one 800-square-foot unit in a large building was $469,800, more than half of which was attributable to construction.

By bringing these costs down, McCormick and Iseman could site affordable homes across San Francisco on plots of land that the city and private landowners have not considered viable for housing.

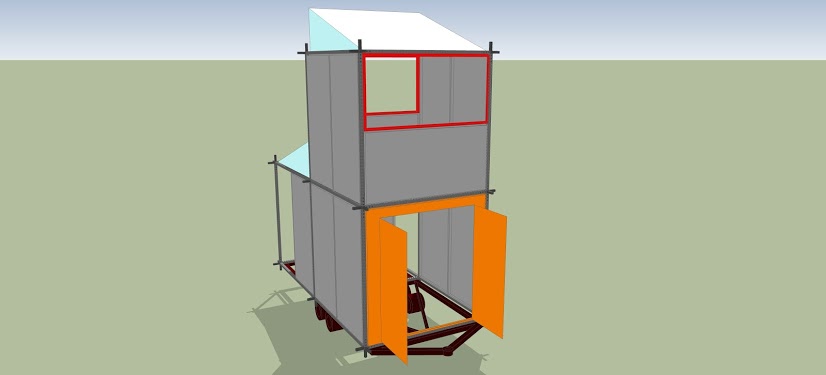

At 64 square feet, McCormick’s cubic “Houslet” is designed to fit into a parking space.

Parking is abundant in urban areas, and possesses many characteristics that make it ideal to build upon.

“While housing land is irregular, extremely expensive and totally site-specific, parking spaces are totally standardized,” McCormick said. “They’re firm and drained, and usually pretty flat. To me, that’s like open-source software: It’s just there, everywhere, remarkably unpriced, or under-priced.”

San Francisco has more than 442,000 public parking spaces, more than one-third of which are off-street in lots and garages, the city’s Municipal Transportation Agency recently reported. Many of those spaces could become obsolete in the near future, as biking and car-sharing become more popular; eventually even on-street parking spaces may be rendered unnecessary. While that scenario may be a distant one, McCormick said, today the city could at least repurpose less frequented parking lots.

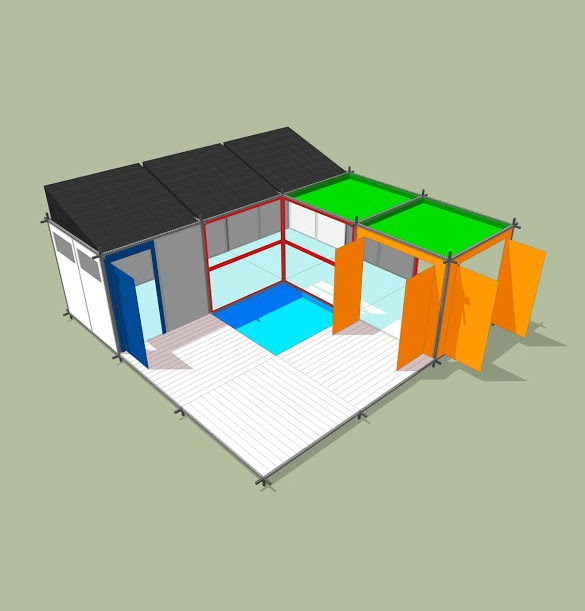

If 64 square feet or a single parking space feel small, there is always the option of expanding. The Houslet’s design is modular, allowing owners to easily to assemble and modify them and create additional rooms by joining cubes together.

“The end result might not be tiny,” McCormick said. “You might build one cube that’s your little sleeping pod or your sunroom, and then you build another one and make it like a kitchen-bathroom unit.”

McCormick is still developing his prototype, but he plans to make the designs open-source so that people could build Houslets on their own. He estimated the cost to buy a custom Houslet that is prebuilt, furnished and equipped for off-the-grid use at between $20,000 and $30,000 — less than 5 percent of the current average sale price of a San Francisco home.

Luxe Shipping Containers

Another Bay Area designer, Luke Iseman of Boxouse in West Oakland, is already living in a home he built from a shipping container, and is in the process of building more.

The 160-square-foot containers, which Iseman buys used from the Port of Oakland, cost about $2,300 — less than what he and his girlfriend used to pay monthly to rent an apartment in San Francisco’s Mission District. The solar panels, a refrigerator, bamboo floors and porch required about three weeks of work, and brought total hard costs to $12,000.

Iseman said he hopes to soon take online orders for fully built Boxouses, and that the first few will sell for $29,000.

But his goal is not simply to sell a product. Like McCormick, Iseman is passionate about educating people who are interested in cheap, minimalistic living.

In addition to providing online plans showing how to make container homes, Iseman is looking to buy property in West Oakland where he and his friends can build a container colony from the ground up, as an example of what is possible.

Once the colony is realized, Iseman will invite people to visit, hoping to show them that these unorthodox abodes are “an acceptable way to live even for people with high living standards.”

The 0.36-acre lot he has in mind would comfortably fit 14 Boxouses, as well as a communal garden and possibly a shared kitchen. The potential to grow vertically by adding stories — shipping containers are designed to stack eight high by simply bolting them together — means that Iseman’s community could potentially hold 114 tiny apartment units.

Infill Development

Because they are stackable, the shipping containers might also be well suited to housing people on the irregular strips of unused, city-owned land scattered across San Francisco.

A 2011 report from the San Francisco Real Estate Division showed that the city owned more than 186,000 square feet of unused surplus land. Those properties could fit almost 1,200 Boxouses if they were laid down side by side, and many more if stacked for multiple stories.

Could these tiny, mobile structures realistically be a solution to San Francisco’s housing woes?

First, San Francisco would have to change zoning laws and building codes that currently prohibit them from being deployed as housing. Right now, the minimum size for a housing unit is 220 square feet, not even close to the Lilliputian dimensions McCormick and Iseman are proposing. To make a big impact, the city would also have to take an inventory of under-utilized land that could be used for this type of housing, and perhaps launch a pilot program.

“What if you declared some part of town to be a housing innovation zone, and allowed one-year permits and entertain all exceptions to building code?” McCormick said. He also proposed a contest, wherein participants could invent new ways to build homes to fit into a single parking space.

“Can you imagine the creativity you would get from people around the world?” McCormick said. “And the message: We are going to make our city open to anyone in the world who can come up with a creative way to live here.”

Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.