Rental, health, child-care initiatives offer little help in relentless real-estate boom

In 1999, during the last tech startup boom, about one-third of San Francisco households were putting more than half their pay toward rent or a mortgage. That was already well above the longtime expectation of federal policymakers that Americans spend less than 30 percent of their gross income on housing.

But as high as the cost of housing was back then, it was nothing compared with now.

By June of 2015 the number of city residents spending more than half their gross income on rent or mortgage payments climbed to 47 percent, compared with 22 percent nationwide, according to a August 2015 report from the real estate data firm Zillow.

London Breed, San Francisco Board of Supervisors president

It is an indication of just how rapidly the cost of living here has gone from expensive to painful for low- and moderate-income residents who used to think they would never have to choose between leaving the city and cutting back. Few would make that assumption today.

Mayor Ed Lee has prided himself on a pro-growth agenda that has helped rocket San Francisco’s housing market — the lever of the city’s economy — into an unprecedented ascent. Now the city is scrambling to catch up with the unintended but predictable consequences of the high-tech business growth phase. Even though two previous booms created similar affordability crises, city leaders never wrote a blueprint to deal with the collateral damage of this one.

“San Francisco wanted the tech sector to come and revitalize the economy,” said Katy Tang, supervisor for District 4 in the city’s southwest corner, who was appointed by the mayor in 2013 and won two subsequent elections. But now, she said, residents in her district are being forced out of their homes. “No one anticipated how much of a boom it would be for our city.”

And people keep arriving in San Francisco to fill both the many new jobs that tech companies are creating and the lower-paying jobs arising in spin-off service sectors.

The economic upheaval motivated the city to embark on a set of costly initiatives and sparked several propositions on the November 2015 ballot. The most expensive, a bond issue for affordable housing, passed with 73 percent of the vote. It will pump $310 million into low-cost residential development. Another measure, which voters rejected, would have temporarily blocked new building in the Mission District to provide the city more time to create affordable options.

And some reforms already set in motion could help rein in the rising overall cost of living. On top of the city’s extensive free health care clinic network for the poor, two programs launching in 2016 aim to augment medical coverage for residents who earn too much to qualify for Medi-Cal, the state’s health plan for low-income residents, but cannot afford medical insurance, despite an array of free services offered by the city.

Other important local policies providing price controls and subsidies include rent control for residents of older buildings, child care credits for low-income families and grants to help small grocers provide fresh food in low-income neighborhoods that lack supermarkets.

But these measures haven’t tamed the crisis in affordability that is increasingly weighing on city residents. Overall, renters, parents of young children and seniors on fixed incomes are experiencing the highest economic pressures as housing escalates out of proportion to other costs, and far beyond the reach of people earning average incomes. The problems are most pervasive among black and Latino San Franciscans, whose incomes are typically lower than those of white and Asian-American city residents.

Decision-makers who have spent years trying to find solutions to the city’s affordability conundrum are themselves having trouble keeping up with the cost of living in San Francisco.

“People are paying ridiculous amounts to live here,” said London Breed, the president of the Board of Supervisors. Breed said that if she lost the flat she shares with a roommate, she could not afford to live in District 5, which she has represented since 2013. Her city salary is almost $115,000 a year.

Breed has watched friends get squeezed out of San Francisco when they had to move or no longer qualified for city assistance. “Sadly, it’s been consistent for many, many years,” she said. “But now it’s reached a level that I don’t know how to describe.”

Boom and bust cycles have washed over San Francisco since the Gold Rush. This is different. Increasing housing costs are so out of whack with the general rate of inflation that anyone who is not protected by rent control, or who loses it through eviction, faces the prospect of sliding down the socioeconomic ladder.

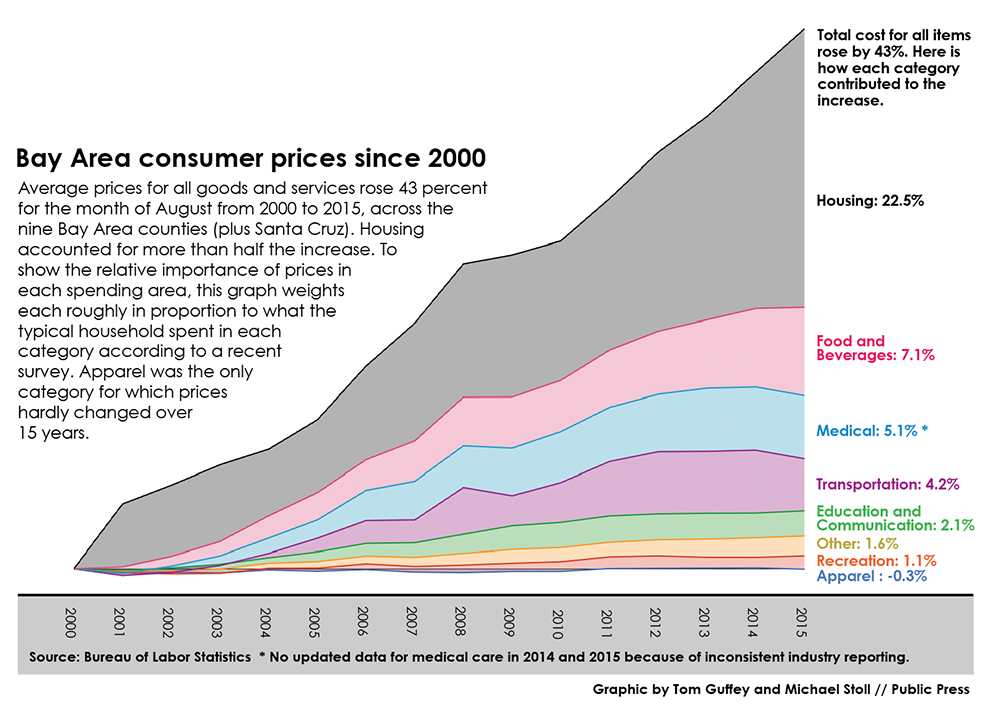

Part of the problem is that the measurements that policymakers use to assess who needs help do not accurately represent the sharp rise in housing costs. These include the federal government’s one-size-fits-all cost-of-living measure known as the consumer price index. The index is referenced dozens of times in local laws setting everything from pension contributions to housing subsidies. But the index — which rose just 2.6 percent in the 12-month period ending in August 2015 — uses a limited number of goods and services, and takes average prices across 10 counties in the region, where the cost of housing has not risen quite as rapidly.

Changes in the federal index have real-world consequences, as 65 million Americans who receive Social Security benefits found out in mid-October 2015, when the Social Security Administration announced that for the next year it would not make a cost-of-living adjustment pegged to the index. That leaves San Francisco seniors and people with disabilities, who rely on monthly Social Security checks, with less buying power than their peers in other parts of the country.

Another problem is that the federal poverty level is outdated. If it accurately reflected the cost of living and the full set of resources received from government programs, it would characterize 24 percent of San Francisco residents — about 200,000 — as poor or nearly poor, said Sarah Bohn, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. The revised rate was developed by the institute in 2012 with Stanford University’s Center on Poverty and Inequality.

This alternative measure is based on the cost of local housing and other necessities minus safety-net supports such as food stamps, Bohn said. “What you count can really change the picture substantially.”

By contrast, under the current federal formula, just 13.8 percent of San Francisco residents and 14.3 percent of Americans were living in poverty.

Expensive Marginal Homes

It is much harder than it was just a few years ago to survive on a moderate income in San Francisco, and nowhere is that more evident than in formerly low-priced neighborhoods. Even downtown flophouses are getting makeovers, where luxury prices do not necessarily mean luxury housing.

Anthony Richmond, a 25-year-old San Francisco native, gave up a $1,000-a-month apartment near Candlestick Park so he could live somewhere nicer and closer to work. He had no idea how hard it would be to find a new place. He stayed with his mother and friends while he was searching, and he thought about moving to another city with lower rent, but that would add commute time and cost. “I work in San Francisco,” he said. “I would rather live in San Francisco.”

During the last tech boom, Richmond could have found a one-bedroom flat to share on his current take-home income of about $1,600 a month as a receptionist at a methadone clinic.

But in this rental market, all he could find was a room with a bunk bed, a sink and a microwave in the 7th Street SoMa apartments — and it costs $1,600 a month. For that price, he had to find a roommate to split the rent.

The property managers billed the place as suitable for students, interns, young professionals, entrepreneurs, artists and “anybody looking for a place to call home in the City by the Bay.” In reality, the 108-year-old, three-story building is a residential hotel that in 2013 was lightly renovated — new carpet, paint and hardwood floors — to make it more attractive to a higher-paying demographic. But there is just one bathroom on each floor and one kitchen for everyone in the building. “We’re crammed in there,” Richmond said.

He doesn’t have much of a choice. He earns too much to be eligible for programs that help low-income residents — even though half of his monthly pay goes to rent a room with no bathroom or kitchen.

Bringing the Bottom Up

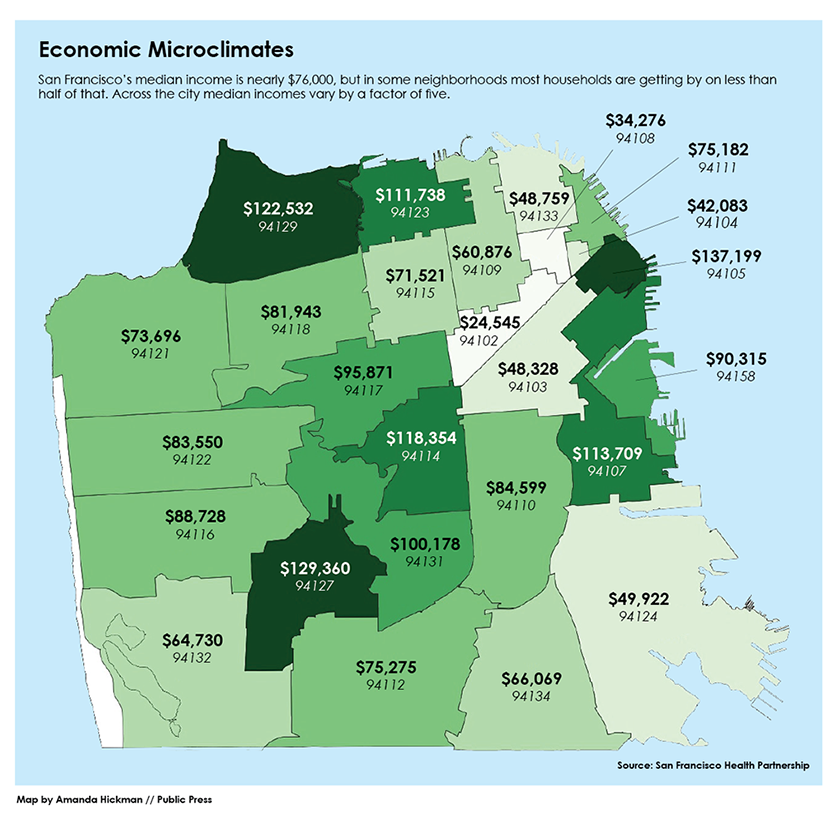

New city-sponsored affordability policies and programs use measures that do not reflect the economic reality for the half of San Francisco households surviving on less than $76,000 that lack subsidized or rent-controlled homes.

At current prices — the median monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment was $4,900 in September 2015 — it would actually take an income of $196,000 a year for a market-rate two-bedroom unit to be affordable by the federal norm, which has 30 percent of pay going toward shelter.

(People who pay more than that have traditionally been considered less able to afford other basic needs such as medical care, retirement and savings for emergencies. Electricity, food and Internet access stretch paychecks even thinner.)

San Francisco voters have long wrestled with the problem of lagging wages for bottom-tier workers. In 2014, they approved a measure making the city the second in the U.S. to raise the local minimum wage to $15 an hour. It rose to $12.25 in 2015, goes to $13 in 2016 and reaches $15 in 2018. But Luke Reidenbach, a policy analyst with the California Budget and Policy Center, said $31,200 a year for full-time work — that is, 2,080 hours at $15 an hour — already falls far short of the current cost of living.

Many housing subsidies offer a life preserver to longtime city residents who otherwise would have been permanently priced out of their hometown. But each relies on different economic criteria, and many of those standards vastly underestimate the number of San Franciscans who cannot afford market rents or ever dream of buying a home.

The federal government’s regional consumer price index does not fully reflect what San Franciscans pay in stores, at the doctor’s office or for rent. Most unhelpfully, it averages out the prices in the nine counties of the Bay Area plus Santa Cruz. “The key word is average,” said Jonathan Church, an analyst with the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, which publishes and updates the index monthly.

Phrases like “market rate,” “consumer price index” and “federal poverty level” do not spring to most people’s minds when the price of eggs doubles or rent goes up. Consumers have to pay what stores and landlords are charging. But these measures and the ways government officials apply them affect how San Francisco designs its social supports, who qualifies for the help and ultimately who can afford to live here.

Proposals for Affordability

City leaders recognize that the cost of living is distorted here, when compared with the national picture and with most other cities. The November 2015 local ballot was stocked with proposals to address soaring costs, though it is not clear that any will have enough effect on the housing market to keep longtime residents in town if they don’t scrimp to pay for the basics.

Proposition I sought to help Mission District residents stay in their homes by temporarily suspending new market-rate construction in the neighborhood. But it did not include a concrete plan for delivering an affordable housing replacement. The city’s chief economist, Ted Egan, said in September 2015 that a moratorium on market-rate construction in the Mission District would push up housing prices there and citywide by tightening the supply, and would neither prevent evictions nor slow gentrification. He suggested instead that the city increase its subsidies for affordable housing and loosen land-use controls.

Proposition J, which passed, will attempt to help longtime businesses stay in San Francisco by giving annual grants of $4,500 to landlords that extend their leases and by giving the businesses $500 per employee. To qualify, businesses would have to meet numerous requirements and prove they have been in the same location for more than two decades.

But there are no guarantees that the cash allowances are enough to keep businesses afloat. The Public Press also found that Proposition J was based on an analysis of business closings before 2011 that Legislative Analyst Julian Metcalf also said included duplicates.

Proposition A, Mayor Ed Lee’s signature $310 million bond issue for building and renovating affordable housing is the costliest. It may not be much more than a gesture, however. That amount of direct funding will cover just 775 apartments at the 2014 average apartment construction cost, which the San Francisco Business Times pegged at $400,000. The measure includes a “bucket” of $80 million for moderate-income renters, but it does not spell out how that money would be spent or whom it would benefit.

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute, a market-oriented policy group in San Francisco, says the city needs policies that directly help current residents who are being priced out. “If we aren’t getting outcomes we want, we are probably not putting the right policies in place,” said the group’s president, Micah Weinberg.

For his part, Weinberg did not even bother to look for a home in San Francisco with his wife when they returned to the Bay Area from Sacramento this year, even though he works here. He knew the city would be too expensive.

Average Residents Drowning

Most residents are unlikely to benefit soon from the new laws. Anthony Richmond can attest to that after signing a new five-month lease in September 2015 on his portion of his shared room. He also took a second job, recruiting customers for a commuter app.

The ballot measures came too late for those already pushed out of San Francisco by the housing affordability crisis.

Nicolas Gauthier-Pin, a Web designer, and his wife, Sue, an art therapist, lived for most of this year in a one-bedroom flat in Noe Valley after a fire forced them out of a house they shared in Daly City. The flat was affordable — as long as their insurance was covering half the rent.

To stay in a comparable place in San Francisco once the insurance ran out would have taken all of Sue’s pay and half of Nico’s. So on Sept. 1, 2015, they moved to Long Beach, where a two-bedroom apartment near the ocean costs them $1,700 a month.

“We can afford to rent something for ourselves and start a family,” Nico said. “Anything in San Francisco was completely out of the question.”

This article is part of a special reporting project on the cost of living in the Winter 2016 print edition of the Public Press.