For the past year and a half, San Francisco has relied almost entirely on complaints from 311 — the city’s nonemergency customer service line — to address homeless encampments, leading to a sharp increase in the proportion of encampments labeled “removed” by city workers, a review of public records shows.

Data from the city’s 311 call center and mobile app show that a big shift happened in August 2018. For the preceding 10 months, about 10% of encampments were removed following complaints. Afterward, for the period ending in December 2019, that proportion shot up to 38%.

The increase in the rate of encampment removals appears to be connected to a shift in responsibility for complaints from Public Works to the Healthy Streets Operation Center, a coalition of city agencies that is tasked with abating homelessness — and which directs city resources chiefly based on 311 complaints.

The change has prompted some city leaders to voice concerns. In August, Homelessness and Supportive Housing Director Jeff Kositsky told an audience at Manny’s Café, a Mission District venue that hosts public speaker events, that reporting encampments to 311 was “a real problem” and urged audience members to stop using the app for that purpose.

“One of the problems with how we address homelessness in San Francisco — a lot of it’s driven by 311 complaints,” he said, adding that if it were up to him, reporting encampments wouldn’t be an option on the 311 app.

Instead, Kositsky said that his department and others should determine where to allocate outreach services, such as shelter and counseling, because “we know better than you where we need to be putting our resources.”

The San Francisco Police Commission would also like to steer away from the current model. On Jan. 15, the commission voted unanimously to back a resolution calling on Mayor London Breed to develop “alternatives to a police response to homelessness.” The resolution called the Healthy Streets Operation Center’s current approach a “costly revolving door” better at moving homeless people endlessly than helping them exit homelessness.

Kelley Cutler, an organizer with the Coalition on Homelessness, said the increase in removed encampments, coupled with the lack of clear data on encampment visits, demonstrated the city’s priority: reducing the visible aspects of homelessness.

“The focus is not necessarily on helping people, but in getting rid of tents and encampments,” she said. “It doesn’t mean that people are going to be helped.”

The mayor’s office and Public Works did not reply to requests for comment about the shift in encampment visit outcomes. The Office of the Controller said that it was not currently using data entered by city workers in 311 status notes for tracking encampment complaint response trends. But in an email last fall, a representative from the mayor’s office pointed to that same data as a primary source for such information.

The Healthy Streets initiative launched in January 2018 as a coordinating platform for city departments, including Homelessness and Supportive Housing, Public Health, Public Works and the Police Department, to better synchronize their responses to the homelessness crisis.

Historically, the coordinated agencies have been at least partially informed by homelessness-related 911 calls and encampment complaints to SF311, a mobile app that allows people to report nuisances such as graffiti, illegally dumped trash and blocked storm drains.

At first, Healthy Streets allowed for more flexibility, Kositsky said in a recent phone interview. Social workers with his department and the Department of Public Health used 311 data and other metrics to track encampment hot-spots, and to decide where to concentrate Healthy Streets resources, he said.

“It was a very slow-roll approach in which our number one focus was to have a deep conversation with everyone we encountered and try to figure out with them what was going to work,” Kositsky said.

But in August 2018, he said, “we shifted from, ‘Let’s just focus on encampments’ to, ‘Let’s focus on 311 calls.’”

After the shift, Healthy Streets directives sent city workers — primarily police and Public Works crews — to every encampment reported to 311. Now, responding to 311 encampment calls is the initiative’s “main focus,” Kositsky said. He added that, while he was unsure who specifically was responsible for the shift, city leaders decided it was necessary because homelessness “continued to be a problem and we decided to experiment with a different approach.”

Some departments actively pursued this tent clearing approach. Former Public Works Director Muhammed Nuru, who resigned Feb. 10, two weeks after his arrest by the FBI on corruption charges, is criticized harshly by advocacy groups for his aggressive stance toward those living on the streets. After widespread outrage flared over his decision to move privately purchased boulders back onto sidewalks to discourage homeless campers, Nuru doubled down, saying the boulders weren’t big enough.

Known by his colleagues as “Mr. Clean,” Nuru went to great lengths to scrub down the streetscape ahead of public events, even sending Public Works crews to clean and remove encampments from the routes to events on Breed’s calendar.

Minutes from Public Works meetings recently revealed by the San Francisco Examiner show that leaders in the department said workers needed to “ramp up efforts to clear” tents, which the leaders called “weeds.” Ahead of a conference expected to draw investors to the city, department supervisors said they were “anxious to show San Francisco in the best light possible.” They stressed the importance of keeping the streets near the conference “clean and clear” with the help of the Healthy Streets initiative.

Since Healthy Streets launched, city officials have acknowledged that in response to a 311 complaint, encampment residents are more likely to be met by police or Public Works crews than by social workers. A 2018 Healthy Streets Operation Center PowerPoint presented by then-Police Department Commander David Lazar claimed this was due to a lack of resources.

The presentation reads: “Ideally, every encampment/unsheltered person would be a mini-resolution led with social service placement.” The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing and the Department of Public Health, the slide deck elaborated, “do not have the current capacity to respond to the volume of requests so SFPD and Public Works will be lead.”

A person who worked for the city during the transition to the Healthy Streets initiative who spoke on the condition of anonymity said that in 2018, the initiative “started dispatching police and Public Works units to any mention of a tent on a street.” These departments “knew that no services had been organized for those people.”

From the Healthy Streets initiative’s launch until November 2019, the homelessness department offered 25,462 referrals for shelter or other services. Of those referrals, 30% led to service connections, occasions when the referred person interacted with the service provider. Referrals from the homelessness department include both those made by Healthy Streets-related workers and those made by providers working outside the Healthy Streets initiative — only a fraction of referrals are made under the initiative.

But the worker said encampment visits often occurred when the Homeless Outreach Team — which usually stopped working at 9:30 p.m. — was off duty. In these instances, the person said that those confronted by police under Healthy Streets typically had not committed crimes more significant than public intoxication or violation of the city’s public lodging laws by erecting tents.

Chris Herring, a sociology Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, spent three years before the launch of the Healthy Streets initiative studying the effects of what he calls a complaint-based policing approach to homelessness in San Francisco — an approach that he and advocates say existed long before the Healthy Streets initiative. Herring found that rising complaints to 911 and 311 led to what he called a “constant game of Whack-a-Mole.” He said the city still plays that game and the results are the same.

“These move-along orders are really punishing to homeless folks, both in the frequency of which they occur and in the depth of impact that they have on people’s material and physical and mental well-being,” Herring said.

When city agencies clear an encampment, Herring said, evicted campers search for new places to sleep. Tents begin popping up in new neighborhoods, prompting housed residents to report the new encampments — in an endless cycle.

“It increases the trouble with sleeping, mental health issues,” he said. “You’re constantly living in a state of stress and terror.”

When city workers respond to encampment complaints, they use the 311 app to log the outcome.

“When 311 cases are closed, the results of the request are recorded by representatives in the field, which can be found in the status notes of the 311 data,” wrote Andy Lynch, Breed’s deputy communications director, in an October email. Status notes are what the Healthy Streets initiative uses to track the outcomes of past encampment complaints, he said. Lynch added that Healthy Streets planned to roll out a new system for tracking service referrals.

A representative from the Office of the Controller said that the office stopped using status notes to track Healthy Streets activity due to “concerns about the quality of the data.” But the Healthy Streets initiative has used status notes in past reports, and city workers continue to use standardized 311 status notes to record encampment visit outcomes.

The city’s shift to a 311-driven system has led to an increase in city workers chasing encampments that aren’t there, an inefficient use of workers’ time and agency resources. The proportion of encampments city agencies could not find rose from 2% between October 2017 and August 2018, to 27% between August 2018 and December 2019. When the Healthy Streets Operation Center is “unable to locate” an encampment, workers often cannot find the reported issue because the reported person has moved.

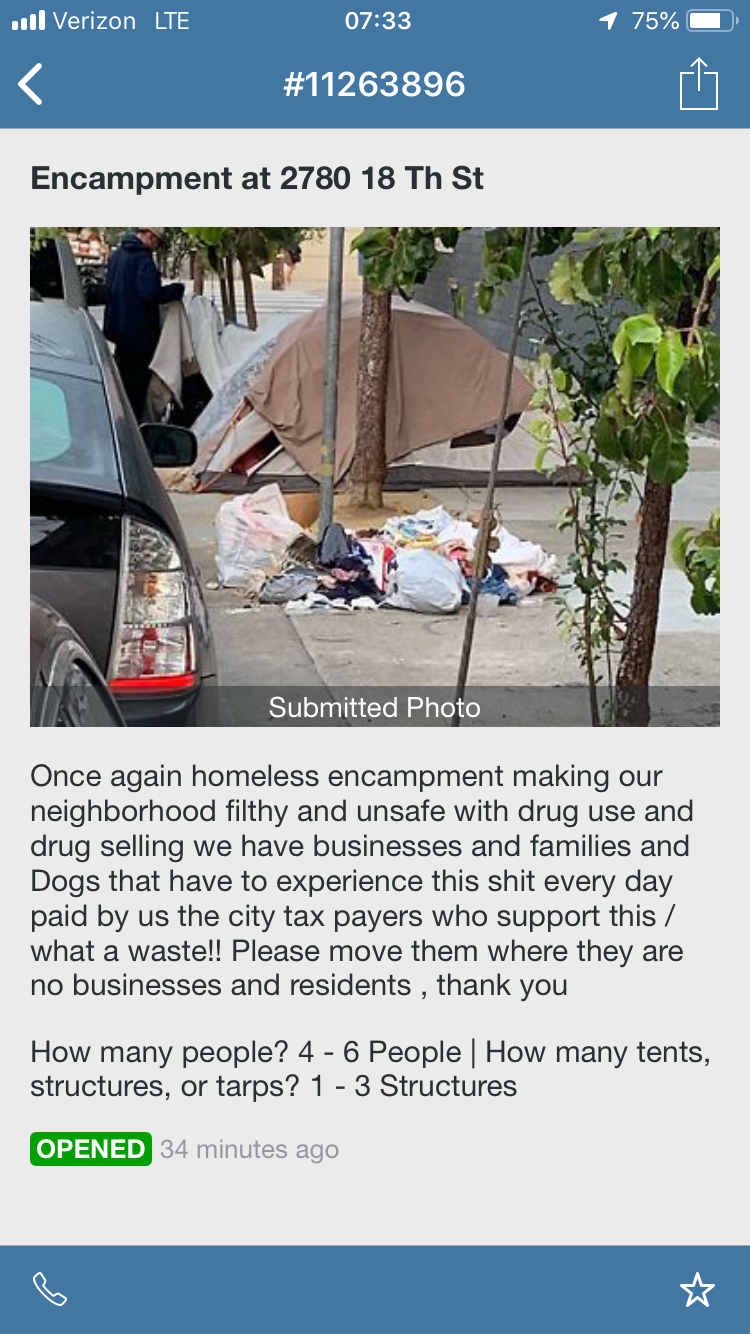

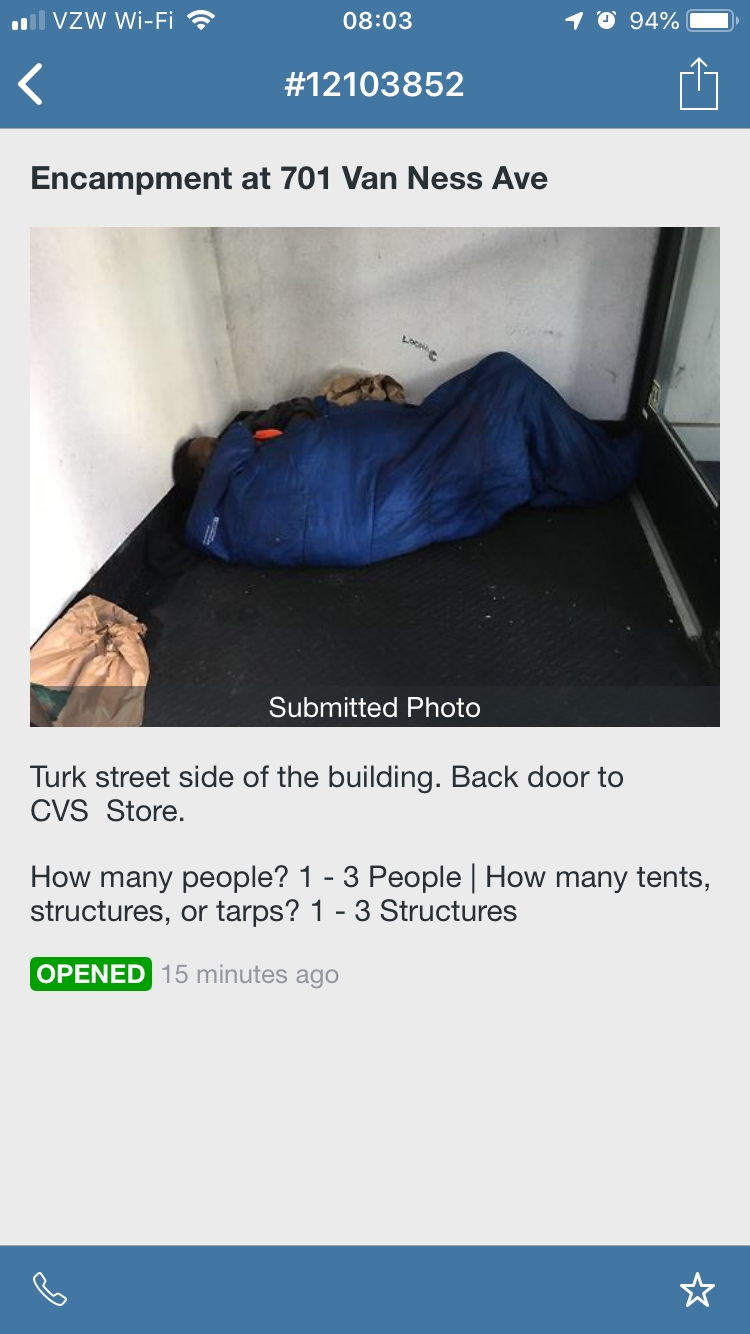

One potential explanation: Since Healthy Streets initiative agencies began responding to every encampment-related 311 complaint, responses to false complaints have also increased. According to Healthy Streets standards, an encampment must include at least one tent or improvised structure, yet SF311 users regularly log erroneous complaints with the app, reporting encampments without structures, such as shopping carts, trash or a person sleeping outdoors without a tent.

Cutler said she had observed a number of false encampment reports to 311 by monitoring the app, which displays a queue of the most recent complaints, many of which include photos submitted by users.

“When you look at the picture, it’s literally one person laying there with a blanket, and it’s not an encampment,” Cutler said. By the time city workers arrive on the scene, the person is usually long gone, she said.