California lawmakers are considering more than 130 bills aimed at solving the housing-affordability crisis. While housing activists are encouraged, the Legislature’s efforts could chip away at longstanding protections in the state’s landmark environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act.

Gov. Jerry Brown is refusing to sign any new efforts to fund housing that do not include changes that streamline the land development process. Brown is a critic of what he calls excessive land-use review under the law, known as CEQA. He has called such a review “the Lord’s work.”

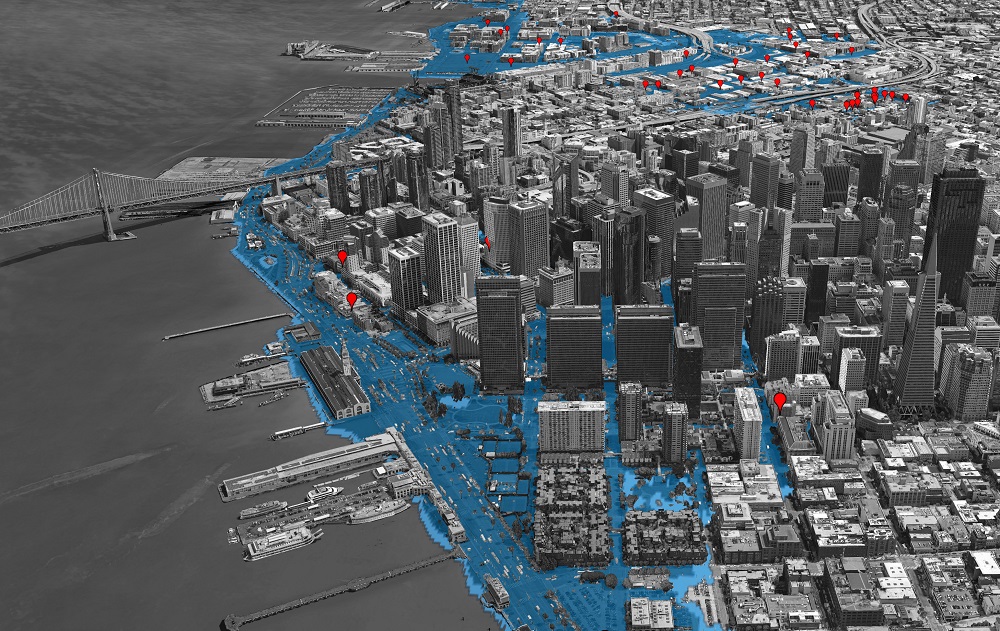

Three of the most prominent bills, including two by legislators from San Francisco, target the review process by limiting the requirement for developers and municipalities to study or mitigate environmental hazards such as air pollution and future flooding as sea level rise encroaches on coastal areas and land ringing San Francisco Bay.

In April, the Public Press reported that during the past decade development interests, led by the California Building Industry Association, pursued a strategy to undermine a key provision of the environmental law that some cities had used to help protect their waterfronts.

[See: Wild West on the Waterfront]

The series was based on a review of thousands of lawsuits and environmental reports. The document search showed that following a late-2015 decision by the state Supreme Court to restrict the use of CEQA to a project’s effect on the environment, and not on potential damage from changes to the climate, developers invoked the court’s language to oppose plans by governments, environmental groups and neighbors to challenge what they saw as projects at risk.

The court said that while developers were not responsible under CEQA for mitigating the effects of their project in the context of rising sea levels, they should still study how a new development might be flooded in the future.

The court’s ruling upset planners, and industry critics say developers are shifting mitigation costs for rising sea levels onto the public. Developers counter that CEQA is a poor tool to regulate for climate change, and that lawmakers should write new regulations.

None of the housing proposals address the regulatory gray zone created by the court. Instead, they go even further in curbing the application of local environmental review. In some form, each of the prominent housing proposals would allow developers to skip the environmental analysis if buildings meet affordable housing and transportation goals.

Kathryn Phillips, director of Sierra Club California, said development interests have sounded a “constant drum beat” against the state’s landmark environmental law.

“One argument is that CEQA is standing in the way of affordable housing,” she said. “There is no evidence of that.”

“In terms of housing, if you want to point a finger, CEQA isn’t the problem,” Phillips added. “What the development interests are doing is taking advantage of a bad situation and targeting something they have always hated. The developers that want to go in and make a fast buck hate the CEQA process. They have their vision and they don’t want anyone standing in the way, and they sure don’t want to mitigate the environmental hazards.”

Instead, she said, housing prices are being driven up by speculation, the cap on property taxes created in 1978 through the approval of Proposition 13 and the dissolution of hundreds of local redevelopment agencies, which empowered cities to invest in certain neighborhoods and generated close to $1 billion a year in affordable housing. Brown led an effort to abolish the agencies in 2011, only to revive a pared-down version of them in 2015.

One of the new housing bills, Senate Bill 540, was written by Sen. Richard Roth, a Democrat from Riverside. The bill would pay cities to create affordable-housing zones, where new development projects would be exempt from environmental review.

In a statement, Roth said CEQA has been used as a “barrier to housing projects even after they have been subject to lengthy public discussion and scrutiny, and been approved by local governments. That is why Senate Bill 540 is critical to improving the quality of life of all Californians.”

But when the Senate Committee on Environmental Quality analyzed the bill, it questioned whether decision-makers and the public would be aware of environmental impacts such as sea level rise without public review. The bill was passed by the Senate on June 1, and is being considered by the Assembly.

According to the committee, a central issue with any bill that gives affordable housing projects a pass on environmental review is that it creates a two-tiered system in which market rate homes are heavily scrutinized for hazards while low-income homes are not (a separate committee on natural resources is reviewing the bill).

Earthquakes, pollution and other hazards do not disappear when they are not studied, the environmental quality committee noted. The committee’s analysis also questioned whether the bill would further transfer the cost of mitigation to the public:

This provision essentially provides that it is acceptable for the financial costs of a project to outweigh potential impacts to public health of people of low-, moderate-, and middle-income households. Regardless of whether this language is taken from the Housing Accountability Act, is it acceptable to grant convenience and cost-savings to developers in the short-term if the long-term consequences may be damaging to the health of residents? A question arises as to why low-income citizens should be deprived of the same protections that CEQA provides for any other project. Environmental protection should be provided regardless of class and this bill does not provide a satisfactory safety net.

While the Roth bill targets CEQA outright, another bill, sponsored by David Chiu, a San Francisco assemblyman and former city supervisor, creates a different workaround. Assembly Bill 73 would change the law to allow cities to designate housing districts and prepare environmental documents for an entire area instead of project by project. Those projects that meet affordability requirements would be exempt from review.

Sierra Club, which opposes any bill that creates a CEQA exemption, says project-level review allows for public participation and a clear understanding of the environmental effects of a particular project.

Chiu said the legislation, which passed the Assembly in June and is being considered by the Senate, would streamline the process and encourage cities to build desperately needed housing. Chiu aide Judson True said the bill takes a responsible approach to the environment “while encouraging housing production in urban areas.”

“There is a problem all over California of jurisdictions not building the housing that we need,” True said. “We think this bill will provide a carrot approach to those local jurisdictions.”

When he introduced the bill to the Assembly in December, Chiu said: “California is facing a severe housing crisis which, if left unaddressed, will continue to threaten our economic competitiveness, our ability to achieve our climate change goals through proper planning, and the fundamental prosperity and success of our residents.” Chiu’s bill does not include an exemption for coastal areas, which is atypical for this type of legislation.

On July 3, the Senate Committee on Environmental Quality published a review of Chiu’s bill. While the committee praised the bill for frontloading the environmental review process, its analysis found that the bill provides “an unnecessary trade-off by creating an exemption at the project level when current streamlining provisions in CEQA should already suffice.” The committee recommended that the project-level exemption be removed from the bill.

The bill was co-sponsored by Bay Area Democratic Assemblymembers Rob Bonta, representing the East Bay, and Ash Kalra, from San Jose.

Hours after he was sworn in as a state senator last December, Scott Wiener, a Democrat, from San Francisco and also a former supervisor, introduced Senate Bill 35, which includes a CEQA workaround but does exempt coastal areas.

Wiener’s bill is designed to allow the state to expedite approvals for new housing. Developers proposing affordable housing in areas that have failed to meet statewide housing goals would be allowed to skip public hearings and the environmental review process. Critics say the bill undermines San Francisco’s affordable-housing requirements.

Wiener’s office did not return calls for comment, but in June, he read a statement before the Senate floor.

“All cities in our state need to create housing if we are going to meaningfully address California’s housing shortage,” he said. “We need to be producing 180,000 units of housing a year in California, but we are producing less than half that, which is inflicting real damage. Our housing shortage is harming our environment, economy, health, and quality of life.”

Under the Bay Area’s Regional Housing Need Allocation for 2014 to 2022, San Francisco should build nearly 29,000 new homes, or about 3,600 a year.

If the Wiener bill passes the Assembly — the Senate already approved it — and Brown signs it, new market-rate projects with onsite affordable housing could be approved “by right,” limiting review and cutting out local planning officials. Brown unsuccessfully pushed a similar proposal last year.

The governor’s sweeping proposal targeted local restrictions on developments as long as they reserved some units for low-income housing. Wiener’s bill does not go quite that far, but it would require San Francisco and other cities approve new housing plans in high-density development zones. But that requirement would only be enforced if a city isn’t keeping pace with its housing production targets.