The ink is drying on the largest land conservation deal in Sonoma County history, and local preservationists say the promise of income from “offset” credits for absorbing atmospheric carbon helped seal the deal.

It will cost $24.5 million to permanently protect the 19,000-acre Preservation Ranch from a long-threatened vineyard and estate conversion process. It’s actually just one part of a vast expanse of 58,000 acres of contiguous preserved land encompassing huge parts of both the Gualala and Garcia River watersheds.

The nonprofit that bought these lands says carbon credits were the key to funding the substantial costs that come along with managing such large tracts. The group’s best estimate is that the credits will yield “several hundred thousand dollars” in annual income, based on similar deals on other parcels.

In buying already-cut timberlands, the Virginia-based nonprofit Conservation Fund has become the second-largest holder of credits in the Climate Action Reserve, one of two international registries for projects likely to become part of California’s new carbon emissions cap-and-trade program.

For Chris Kelly, the fund’s California program director, the Preservation Ranch deal caps more than a decade of work that began when North Coast timber companies seemed likely to start selling off their lands.

“We were coming to the end of this decades-long trend of depletion,” Kelly said. But after timber companies had consolidated ownership of huge areas and logged them out, the trend seemed to be toward creating ever-smaller parcels. Bad as clearcutting had been, fragmentation could have been worse.

“When we started doing this in 2003, there was one 58,000-acre parcel, a 28-mile stretch of forest lands in one owner,” he said. But as lands got chopped up, it increased the urgency of preservation.

Kelly’s organization was able to purchase the northernmost 24,000 acres, the Garcia River forest. But the southern portion, Preservation Ranch, was slated for development into vineyards and estates on as many as 60 parcels.

“The very scenario we proposed to stop was now unfolding before our eyes,” Kelly said. “Now in 2013, we will have reassembled that original 58,000-acre parcel over the course of a decade. Carbon offsets have played a significant role in that, as have voter-approved bond funds.”

FINDING THE MONEY

In some respects, this is a typical conservation deal writ large: A complex ballet of funds had to come together from the Coastal Conservancy ($10 million), the Sonoma County Agriculture and Open Space Preservation District ($4 million), the Sonoma Land Trust ($1 million) and the Conservation Fund ($9 million). (The Santa Rosa Press Democrat examined the politics of the deal.)

That buys the land. But then there’s the question of how to manage such huge parcels, with dozens or hundreds of culverts, eroding logging roads and other major maintenance costs.

“Most of land conservation these days is taking an already-fragmented landscape and trying to put it together,” Kelly said. “In this case, the challenge wasn’t how to put it together, but how do you even think of conserving at this scale?”

At Preservation Ranch and its sister watersheds to the north, the Conservation Fund aims to pay for ongoing management with a combination of carbon credits and what Kelly calls “light-touch forestry.”

The carbon offset credits are the key to Kelly’s model and will make up some 90 percent of the revenue off the land for the near future. (After several decades of timber growth, there will be more revenue from selective harvesting.)

Kelly said he did not have precise revenue projections yet, but anticipated carbon credit revenues of hundreds of thousand dollars per year.

According to a case study the Conservation Fund commissioned on another project, it expects to generate about $7 million in credits over 10 years. But that 16,000-acre tract, in the Big River and Salmon Creek forests, is much more productive, with larger trees.

The uncertainty about the productivity of California timberland is a big problem not just for carbon credits, but in helping to determine how much can sustainably be harvested.

“One of the risks and one of the reasons we have been acquiring forests in Northern California is that the redwood forests have been intensely managed for the last 70 years at a pace faster than the forest grows,” Kelly said. “The forest now is so depleted of commercial timber that there’s very little value as timber, so what do you do? Maybe you sell the parcels, maybe you convert it to vineyards, which was the [proposal] at Preservation Ranch.”

The deal was even promoted as a way to preserve some forestland, while converting other tracts to vineyards. To some critics, it looked like the developers wanted to get credit for leaving trees on hillsides so steep they couldn’t be used anyway.

Kelly said the carbon market offered a different path: “Carbon offsets allow us to be very patient and essentially wind back the clock to the way these forests were in the middle of the 20th century. Over time, we could harvest much more closely to the annual growth, but the carbon offsets let us take a break. That’s the idea and that’s what’s allowed us to manage these large tracts and improve conditions not only for terrestrial species but also for aquatic species.”

CLOSE TO HOME

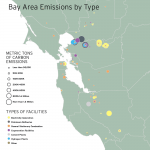

There has been significant controversy about whether the state should accept forest-based credits, with much debate revolving around whether credits for projects in other countries — currently the focus is on Chiapas, Mexico, and Acre, Brazil — should be exchanged for the right to pollute here.

“People want a sense of proximity of the solution to the problem you’re trying to mitigate,” Kelly said. “Our projects are in a highly regulated state, and in the state that is going to administer the regulations, and we’re not locking up the forest, and we’re doing timber management and watershed restoration, so there will be jobs. And, though they’re not in East L.A., at least our forests are proximate to the problem we’re trying to address.”

There is also the uncertainty of whether forest offsets will really lock in improved forest practices for the long term and reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions.

“There are tremendous variation, conflict of interests and uncertainty involved in the claims and activities that sequester carbon or avert greenhouse gas emissions and thus generate credits,” Kathleen McAfee, an international relations professor at San Francisco State University, wrote in an email.

Kelly speculated that few traditional forest landowners in California would want to deal with the commitments required. “To enter into a forest-based carbon offset project requires the owner of the land to make a 100-year commitment to protect that carbon they are sequestering,” he said. And because California’s key global warming law only covers emissions through 2020, “there might be only seven years of carbon sales. It’s so uncertain that a private landowner is not going to make that commitment yet. As a nonprofit, we are morally committed to the long term. That’s why we bought these lands — to keep them from getting subdivided and converted. That’s our mission.”

STILL EXPLORING

One of the Bay Area’s foremost ecologists, Peter Baye, happens to live just a few miles from Preservation Ranch, in the tiny hamlet of Annapolis. He has fought the Preservation Ranch vineyard conversion from the beginning, on behalf of the Friends of the Gualala River.

“There’s a lot of diversity in the watershed,” Baye said, “and it’s also mostly private, so there’s been very little exploration. When they started doing surveys for Preservation Ranch, they were finding mountain lion dens and salamanders they weren’t identifying, sightings of fishers and elk not confirmed. It’s been scarcely explored. The only modern surveys that have been done were done for this project.”

And even though the land was severely affected by clear-cutting in the 1950s and 1960s, it seems to be recovering remarkably well, Baye said, especially compared with the Russian River next door. Here, there was never much agriculture. Creeks stripped of cover by logging are once again shaded, which make them better fish habitat. And the streams are steep and fast, so they flush sediment quickly.

Things look pretty good now, but Baye stressed that there is much more to learn about the forest.

“This came out of the timber harvest era that didn’t have surveys,” he said. “It really is a jump from the 19th century to 2013 in terms of what we know about the landscape. I just know what’s around the edges and up the streams. It’s pretty amazing.”

This story is part of a special report on California’s cap-and-trade program, in collaboration with Earth Island Journal and Bay Nature magazine. It was made possible by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Buy a copy of the summer 2013 print edition through the website, or consider becoming a member and get every edition for the next year.