Over coffee at Atlas Cafe in the Mission recently, Adriano Farano wanted to show me an article from a technology site he had noticed earlier that day. The Paris-based entrepreneur (and currently a Knight fellow at Stanford) took out his iPad 2, touched its screen, loaded Google and found the link.

Within seconds, we were sharing the story, including a set of impressive data visualizations.

It’s sometimes easy to forget that just 10 years ago, none of this — other than the coffee — could have happened. But back then, there were no Wi-Fi networks, no smart mobile devices and no cool graphics. Even the tech site where the story was posted had not yet been born.

Google was still a little startup and had indexed only a tiny portion of the Web, and most news operations were not sharing their breaking stories online anyway.

As fast as this new media era has emerged, and as profoundly as it has transformed how we access the news, we have to remember that all of the technologies involved are still at an early stage of development — and therefore we should expect the changes coming over the next 10 years to be even greater than what we have experienced to date.

Today, San Francisco sits at the epicenter of a brand new tech boom revolving around several thousand variously funded startup companies. The organizer of the premier mixer for entrepreneurs in the city, Christian Perry of SF Beta, estimates that there are between 4,000 and 6,000 such outfits in the city. (His current mailing approaches 5,000.)

Many other ventures can be found in the Valley or in tech-focused business strips all over the East Bay and Marin.

Aside from the social, local and mobile innovations, other influences on the news include online gaming, collaborative content creation and smarter software that can find its own solution to problems not anticipated by its human creators.

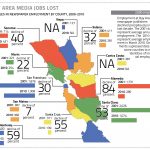

At the same time that all this feverish activity is taking place — and some would say because of it — there have been massive dislocations among the people who traditionally dug up the news.

Only a shadow of the former news staff at the San Francisco Chronicle remains, while the company’s iconic building at the corner of Fifth and Mission is filling up with new tenants, most working for tech startups.

So how might these new ventures impact the future of journalism?

Social media: You are the editor

One venture already having an impact is Storify, which in late April launched a new platform for publishing and distributing stories. Within a week, the death of Osama bin Laden prompted many news organizations to gather reactions from Twitter, Facebook, Flickr and other social sites by using a simple drag-and-drop function.

The nonprofit Bay Citizen used it to compare the subtle differences in reactions to bin Laden’s death from people in New York, where there was unbridled joy, and San Francisco, where the generally joyful mood was more muted.

“It’s like remixing content,” said Burt Herman, a longtime foreign correspondent for the Associated Press before co-founding Storify. Plus, by embedding social media posts into their stories, journalists can set off a more organic, viral distribution method based on retweets and “likes” by the people they quote.

This results in what Herman calls “living stories,” which continue to evolve as new contributors add material and recirculate them around the Web.

In this way, Storify helps recruit the crowd to the business of creating and disseminating stories. Everyone who contributes a comment or a link becomes part of the community editing the news.

Local media: Reporting = Mapping

Another aspect of the data gold rush in the Bay Area revolves around how to match information about what is happening right around you in as close to real time as possible, based on your physical location at the moment.

You see parts of this at Foursquare, Facebook and several new Google products — especially Latitude, a social-mapping and check-in service similar to Foursquare.A smaller player in the geo-coded content category is Fwix, which uses technology to better address the “hyperlocal” strategies being implemented nationally by AOL’s Patch.com, Examiner.com and others.(Discosure: the author serves as an outside adviser to Fwix.)

Fwix has aggregated local news and search in 61,000 cities in seven English-speaking countries. It filters local information from some 35,000 sources, including news organizations, blogs, events, reviews and social media. “We want to be the default local content company,” said the company’s CEO, Darian Shirazi.

Its geo-coding and content classification technologies are the key to its approach, as opposed to the human networks employed by Patch.

The sweepstakes in the competition to figure out local will help determine the future of journalism in innumerable ways, from the kinds of stories that get covered to the connections between local content producers and consumers, as well as the advertisers who will fuel these localization networks going forward.

Mobile media; ‘Playing’ the news

Mobile apps for tablets, like the iPad, promise to reshape journalism more than Web pages ever did, because they travel the same way print magazines, newspapers and books do — anywhere you want them to.

Kiip is a startup that provides mobile gamers with “real rewards for virtual achievements.” When a player wins or otherwise gains an achievement, Kiip gives the player a voucher for a reward from sponsors such as beauty site Sephora or 1-800-Flowers. The mobile Web also has the potential for new ways to finance content creation through innovative advertising models.

Kiip’s 19-year-old founder Brian Wong calls these “perfect engagement moments,” when people are more willing to receive a message from a brand than with the more intrusive advertising like banner ads.

While it’s difficult to imagine a direct corollary for news content as it is presented today, it may be that journalism needs to take a page from gaming. With multimedia interactive formats on mobile devices, perhaps tomorrow’s audiences will prefer to “play” the news with the tools that companies like Storify and Fwix are developing in favor of the old model passive consumption.

That’s precisely what Adriano Farano and I were speculating about back at Atlas Cafe. Farano noted that all of the relevant digital technologies are simultaneously becoming both more personal and more social, or “per-social” by his phrase. In this context, gaming may offer journalism some clues about how to adapt.

Startups like Storify, Fwix and Kiip are just the tip of a huge iceberg. An important rule of thumb I’ve learned in the past 16 years of working with Internet startups is that disruptions of this magnitude will reverberate through the media world for many years to come.

In the fall of 1995, for example, I helped David Talbot and a small team of expats from the old San Francisco Examiner launch Salon, which was (along with Slate) one of the first two U.S. websites devoted to high-quality, traditional-style journalism.

Over the next few years, Salon broke countless big stories in arts, culture and politics and won lots of well-deserved awards, but by early in the new century, it had fallen back along the steep curve of innovation and had to resort to ill-conceived attempts to restrict access to its content — attempts that all failed miserably.

Despite recent attempts by CEO Richard Gingras to help Salon adapt to a rapidly changing media landscape, the company continues to shed staff and lose money, much like the newspaper industry it once seemed destined to supplant.

Even as they attempt to adapt, many old (and new) media companies will struggle — especially those, like the New York Times, that pursue dead-end strategies like paywalls or other attempts to lock up content that wants to be free.

What would make much more sense for all of them would be to stop fighting technology and join forces with the innovators to help perfect the platforms, networks and tools that will determine how journalism is practiced 10 years from now.

A recent article from Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab noted that there is real journalistic value in “having a staff that walks in the worlds of both journalism and programming: the ability to see things in news stories that others may have missed. So much news now starts with documents and information, not just catastrophes and events, and it’s necessary to have people who can stare through a block of data and see the story on the other end.”

This refers to the data visualizations that are becoming a significant component of digital content, and there’s a certain synchronicity at work here. Every successful tech company, from Google on down, is really a data-mining company.

In Google’s case, part of the reason its search results seem so “smart” is that they are based on all of the information about you the Mountain View-based company can glean from your activity on Gmail, Blogger, maps, translation tools, calendar, docs, YouTube and all its other free services.

Some have fears about all this data collection. Recent controversies involving the way Apple’s iPhones and other mobile devices have been tracking users’ locations via nearby cell towers and Wi-Fi hotspots are a reminder that many people remain uncomfortable with the surreptitious method of monitoring their online behavior that is a cornerstone of Google’s (and others’) success.

All of which means the rise and fall of corporations and the future of journalism will to a large degree revolve from now on around data — how it’s collected, exploited and displayed.

The future has arrived and it’s called the Age of Data.

The author serves as an outside advisor to a number of startup companies, including one mentioned in this article, Fwix.

Forty-six individuals donated a total of more than $1,000 to help make possible a special report on changes in media in the Bay Area via the journalism micro-funding website Spot.Us

This story appeared as part of the Public Press' Spring print edition media package of stories.