Designed to combat San Francisco’s long-standing housing shortage, an empty homes tax on the November ballot, Proposition M, would apply to multi-unit residential buildings with prolonged vacancies. Voters will decide the fate of the measure that has garnered support and criticism for its exemptions and low tax amount.

While revenue from the empty homes tax would go toward rent subsidies and affordable housing, its architect, Supervisor Dean Preston, stressed that its primary purpose is returning vacant units to the market.

“The goal is to motivate those who are keeping properties off the market to rent it out or sell it to someone who wants to live there,” he said.

Owners of single-unit buildings and duplexes would be exempt from the levy.

Some housing experts said the tax’s exclusion of one-unit and two-unit buildings weakens its effectiveness, leaves millions of dollars on the table and sacrifices thousands of residential units that could be used to increase the housing supply. Others wondered whether the tax penalty would be high enough to change behavior and persuade owners to return vacant units to the rental market.

“If we’re going to be placing this tax on the ballot, it should incorporate all the units that are potentially diminishing the amount of housing stock available for rent,” said Sarah Karlinsky, a senior adviser for local public policy think-tank SPUR.

The tax would take effect Jan. 1, 2024, and would range from $2,500 to $5,000 per unit based on size. The tax owed would double each subsequent year of consecutive delinquency.

Subject to the tax are owners of residential buildings with three or more units who have kept at least one unit vacant more than 182 days out of the year — or roughly six months.

When drafting the legislation, Preston relied on a report from the Board of Supervisors’ Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office submitted to him in January 2022. The report used the most recent data available at that time from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, and found that as of 2019, San Francisco had 40,458 vacant units, comprising nearly 10% of the city’s 406,399 housing units.

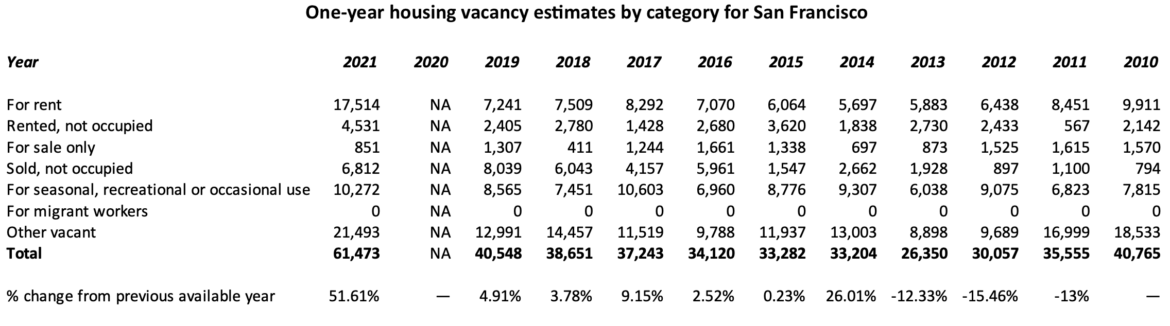

This staggering figure illustrates a long-standing vacancy problem that has worsened over time, Preston said. An updated version of the American Community Survey lends credence to his concerns, showing the vacancies increasing faster than housing construction. In September 2022, the survey released its latest report with data for 2021 and found 61,473 units vacant. Separately, the Census Bureau reported a total of 412,268 housing units in San Francisco as of July, 1, 2021. The survey further breaks down vacancies by category: for rent; rented, but not occupied; for sale only; sold, but not occupied; for seasonal, recreational or occasional use; for migrants; and other.

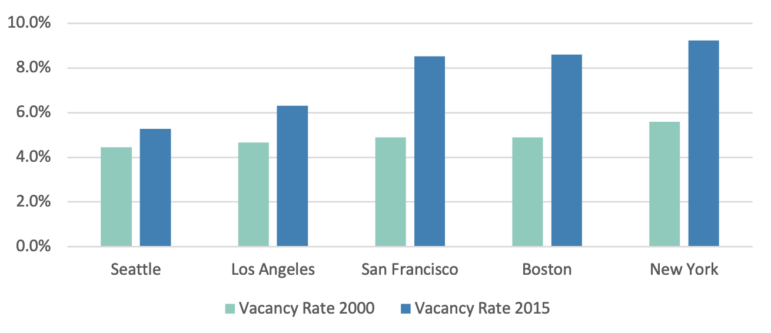

A 2018 report from the Terner Center for Housing and Innovation at UC Berkeley illustrates that, historically, San Francisco has experienced higher rates of vacancies than other big West Coast cities, like Seattle and Los Angeles.

Using data from the Census Bureau and the American Community Survey to examine vacancy rates over time, the report found that San Francisco experienced a vacancy rate of approximately 5% in 2000, while the Bay Area’s vacancy rate was closer to 3.5%. The report cites San Francisco’s higher percentage of renters, noting that areas with larger renter populations experience more turnover, resulting in a higher count of short-term vacancies.

Housing vacancy rates for San Francisco and the Bay Area continued to diverge, and by 2005, the city’s vacancy rate was three percentage points higher than the region’s, doubling the difference between the two geographies from 2000. San Francisco’s vacancy rate has not increased every year — the city saw a decline in vacancies from 2010 to 2015 — but the upward trend has continued over time.

In arguments supporting the tax designers wrote that prolonged vacancies limit the supply of available housing units and work against the city’s housing objectives and that long-term vacancies may decrease economic activity.

Karlinsky said that a high functioning housing market benefits everyone, particularly those who have less money to compete for a scarce resource like housing. By placing more units back on the market and expanding the available housing stock, those who earn less would stand to benefit the most, she said. “I think it could potentially be a good tool in order to do that.”

Preston said the main drivers of prolonged vacancies are real estate speculators who purchase property in a manner akin to investors purchasing shares on a stock market. Rather than renting out the property, they buy it, hold it, and sell it when it’s more valuable later.

This behavior, he said, occurs primarily in newer condominium buildings where a single owner may acquire multiple units and hold them off the market until the value appreciates and then flip the property.

“We also see entire buildings in my district and then really across the city, where real estate speculators have bought the building, kicked everyone out of the building, and they’re just holding it vacant again year after year after year,” Preston said.

He said he hopes the empty homes tax will limit such behavior.

Proponents and critics favor alternate approaches

As the November election draws closer, housing advocates are divided on the measure.

Corey Smith, executive director of the Housing Action Coalition — a nonprofit that advocates for building homes that are affordable or below market rate as well as market rate homes — said that building more houses should be prioritized. Since the empty homes tax does not focus on housing production, his nonprofit does not support the measure.

The San Francisco Apartment Association, a property-owners group with thousands of members, is also against Proposition M, similarly citing the lack of housing production as the reason for its opposition. Janan New, the association’s executive director, said that expediting housing construction is a better method for addressing San Francisco’s housing crisis than punishing owners of vacant units.

The measure has found some support, however, from housing advocacy group SF YIMBY. Joe DiMento, the organization’s San Francisco lead, said that discouraging landlords and homeowners from keeping units off the market by means of a vacancy tax makes sense, theoretically. In the context of a city with so many unhoused residents, having tens of thousands of units sitting empty, “feels like the wrong thing to do,” he said.

Still, DiMento said he doesn’t have much confidence in the measure’s ability to put a real dent in the housing crisis, adding that he finds the exemption of single-family units and duplexes particularly problematic. DiMento said that housing legislation in the city often has too many carve-outs and exemptions in general, rendering the measures meaningless.

To Preston’s point that more vacancies are concentrated in multi-unit buildings, DiMento doesn’t believe that justifies the exemption for one and two-unit buildings, noting that one person or entity could own multiple properties that are sitting vacant, including single-units and multi-units alike.

“Why does a one-unit building get an exemption and the four-unit building doesn’t?” he asked.

SPUR declined to support the measure, because it also asserts that one-unit and two-unit buildings should be subject to the tax, Karlinsky said. She added that when examining vacant units, it’s critical to look at the types of vacancies. She said the tax focuses on units that are being held as investment properties that aren’t contributing to the housing stock, and that those units are typically in the “sold, but not occupied” or “seasonal” categories.

The Budget and Legislative Analyst’s report found that vacant units are primarily concentrated in South of Market, downtown and the Mission District. Karlinsky agreed that many of the “sold, but not occupied” or “seasonal” vacant units are found downtown or South of Market. However, she added that these vacant units are not limited to areas like these that are primarily multi-unit housing. She highlighted Castro and Sunset as neighborhoods with vacant units that will be exempt under the empty homes tax.

“We don’t think that the data bears out that these one-unit and two-unit buildings aren’t deserving of being taxed,” she said.

Recently released figures from the American Community Survey based on 2021 data show that vacancies categorized as “for rent” now account for the second largest number of vacant units in San Francisco, with those in the “other” category — including, but not limited to, units held vacant for family or personal reasons, units undergoing repair, units subject to legal proceedings and units being kept vacant for future sale — remaining the most common type of vacancy.

“We saw a huge jump in the ‘for rent’ category, and everybody is aware of the sort of trends of the pandemic, where a lot of folks moved out of the city and a lot of apartments that were attempted to be occupied are now on the market,” said Kyle Smealie, legislative aide to Preston.

Another component of the tax sparking debate: the dollar amount. Shane Phillips, a Los Angeles-based urban planner and policy expert, said he doesn’t think the tax is high enough to change owners’ behavior.

“When creating a vacancy tax, it’s important to think about what you want to achieve. There are two goals and they don’t have to be mutually exclusive,” he said.

Phillips said the tax’s authors needed to strike a balance between making it punitive enough to encourage owners to return the units to the rental market, but lenient enough that some will just pay the tax so that revenue can go towards affordable housing. The revenue generated by this measure, he said, would be much higher were it not for the one-unit and two-unit exemption.

Preston said he concedes that the tax may not change much behavior during the first year, but points to the tax’s escalating structure, noting that it doubles in size each consecutive year of delinquency.

“The biggest problem is the prolonged vacancy, and if for some reason there’s a vacancy for seven months in one year and then they lease it out and it’s good to go, you don’t want a punitive tax rate in that first year,” he said.

This escalating scale, he said, provides balance, in that it leaves room for an owner who has an “off year” to not be hit with a massive tax, but puts pressure on corporate landlords who hold units off the market for years as a business move.

Revenue impact: affordable housing

Revenue derived from the tax will go towards the creation of the Housing Activation Fund, which would primarily fund two programs: One program would provide rent subsidies for seniors and low-income households, and another would pay for the acquisition and rehabilitation of multi-unit buildings in which at least one-third of the units are unoccupied, for affordable housing, and the operation of those buildings.

According to the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office report submitted to Preston earlier this year, the city’s affordable housing production is well below target as required by the Regional Housing Needs Allocation, a multi-year housing-unit needs target prepared by the state’s Housing and Community Development Department.

The report found that in 2020, some 4,044 units were added to the housing stock in San Francisco, 14% decline from 2019, but still 31% above the 10-year city average of 3,082 units added annually. Of the units added in 2020, only 818 units, or 20%, were affordable for very low, low or moderate-income level groups, which is defined as below 120% of median income in the area, i.e. $138,500 for a family of three in 2020. This is down from an average of 1,037 affordable units per year from 2015 through 2020.

Implementation and enforceability

Pat Cochran, the empty homes tax campaign manager, said the measure is modeled after a residential vacancy tax introduced in Vancouver, Canada, in 2017, which is credited for bringing more than 18,000 units back to the rental market since its implementation.

San Francisco’s comptroller estimates that this measure could generate additional revenue for the city exceeding $20 million in tax year 2024, $30 million in tax year 2025, and $37 million in tax year 2026. However, revenue may be lower if the tax achieves its goal of reducing the number of residential vacancies.

The mechanics for enforcing the tax are still being worked out and will be finalized if the measure passes in the November election. Like the city’s commercial vacancy tax, Preston said tracking vacancies will rely heavily on self-reporting, with owners having to sign off under penalty of perjury on the vacancy status of their units. The city’s Rental Registry will be a major component of tracking vacancies. Beginning July 1, 2022, owners of buildings with 10 or more units are now mandated to report information about their units to the Rent Board Housing Inventory.

Preston said that monitoring utility bills, like electricity and water usage, is a useful tool for enforcement. For example, he said if an owner of a 10-unit building declares that only two units are vacant, but water and electricity usage are zero for the year, it will be easy for the city attorney or treasurer to bring an enforcement action against the owner.