OPINION

Most of the time, the video cameras we walk past every day are innocuous fixtures in the background. But because they’re so prevalent, when law enforcement officials gain access, webs of security cameras can be used as surveillance networks to monitor the everyday behavior of a massive number of city residents – and in many cases, the public would know little to nothing about it.

Studying the surveillance technology in use by law enforcement in the Bay Area has led us to believe camera registries and networks are so prevalent that residents could rightly question whether their purpose is for surveillance instead of security. But uncovering how and when these cameras and other technologies are being used is not easy.

While law enforcement agencies are technically complying with a recently enacted transparency law, three of the region’s largest police forces disclose their capabilities in formats that make it difficult for a layperson to learn which technologies are in use, and how, without already knowing where to look.

Listen to the authors of this piece at a recent Public Press Live webinar:

Camera surveillance ubiquitous

Camera networks and registries are pervasive in the Bay Area, which means people going about their everyday lives in communities that employ these tools may not realize how likely it is that their activities are recorded and retained by a system designed to fight crime and enforce laws.

Camera networks vary in terms of ownership. Camera registries, for which residents register personal video surveillance systems with local law enforcement, rely on residents voluntarily working with law enforcement agencies and are rarely properly documented under Senate Bill 978, a recently enacted transparency law. Other networks are managed directly by law enforcement.

We counted 36 camera networks in the Bay Area, of which 29 are directly run by law enforcement agencies. Some are provided and run by private entities. One such example was detailed in a recent New York Times article on a wealthy San Francisco resident who bankrolled an expanding network of privately-owned security cameras. The Electronic Frontier Foundation revealed in July that the San Francisco Police Department was granted remote access to this private network to surveil protestors — counter to local privacy law, which would have required city permission, the foundation alleged.

The camera network operated by the Moraga Police Department in Contra Costa County is an example of smaller, more targeted use of surveillance cameras. According to documents published by the Moraga Community Foundation in April 2017, cameras were installed at strategic locations and accessed by police investigators only in relation to solving a crime.

Most law enforcement agencies fail to specify when they will delete the data they collect through these networks. For example, the Fairfield Police Department states in its policy manual that data should be retained for a minimum of 30 days. The Cloverdale Police Department states recordings must be stored for a minimum of one year. Neither policy manual specifies a limit for how long the agencies can hold recordings that are not being used in legal proceedings.

Camera registries, which law enforcement agencies can only access by calling on a resident who has voluntarily registered their video system, are often framed as an ideal example of community-law enforcement agency partnerships and are touted as strengthening the relationship between citizens and law enforcement.

In our search, we were unable to locate lists of participants to understand who is signing up for such partnerships, or how many people participate. Just three of the 32 agencies that we know use camera registries have disclosed policies detailing the governing functions of these programs, which is required under SB 978. This means that for residents under the jurisdiction of the 29 agencies with no published governing policies, there is no way for individuals to know more about the camera footage that could be used to surveil them.

Body cameras, license plate readers top list of surveillance technologies

To address this lack of transparency, California Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 978 into law in October 2018. It requires, by January 1, 2020, that each of California’s local law enforcement agencies conspicuously post their standards, policies, procedures and training materials on their official websites, to provide their communities with a comprehensive understanding of what capabilities and actions they should expect from their police forces.

While this information was not secret before SB 978, access required specific and individual requests through the California Public Records Act. Senator Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) authored SB 978, stating that he hoped, among other benefits, the law would “build mutual trust as well as improve police accountability.”

We used both open source media like newspapers and law enforcement agencies’ own SB 978 documentation to examine and record the surveillance techniques and capabilities employed by law enforcement agencies in the Bay Area. We studied 80 law enforcement bodies, including some that are part of universities or community benefit districts, which are not subject to SB 978’s disclosure requirements. Raw data from all 80 agencies provide an aggregate view of how law enforcement operates throughout Alameda, Sonoma, Solano, Contra Costa and San Francisco counties. We created a spreadsheet and map meant as a tool for anyone doing specialized research on police surveillance in this region.

We found that the most prolific technologies in use are body-worn cameras, automated license plate readers, camera networks and camera registries, as seen in the table below. Of the 80 agencies studied, 85% employ either camera networks, camera registries or both. We also found that three of the region’s largest police forces disclose their capabilities in ways that make finding relevant information tedious and difficult.

| Technology | Agencies Using Technology |

| Body Worn Cameras | 55 |

| Automatic License Plate Readers | 41 |

| Camera Network | 36 |

| Camera Registry | 33 |

| Drones | 16 |

| Gunshot Detection | 9 |

Disclosures bring only limited transparency

Some agencies’ disclosure documents comply with the letter, but not the spirit, of SB 978. The majority — 51 of the 67 law enforcement agencies examined — simply published their manuals in Portable Document Format (PDF) on their websites, with the text recognizable to a browser’s search function, making it easy to search specific terms like “Body Camera” or “Automated License Plate Reader.” A digital search for key terms encompassed the entire publication and required no familiarity with naming conventions or file format.

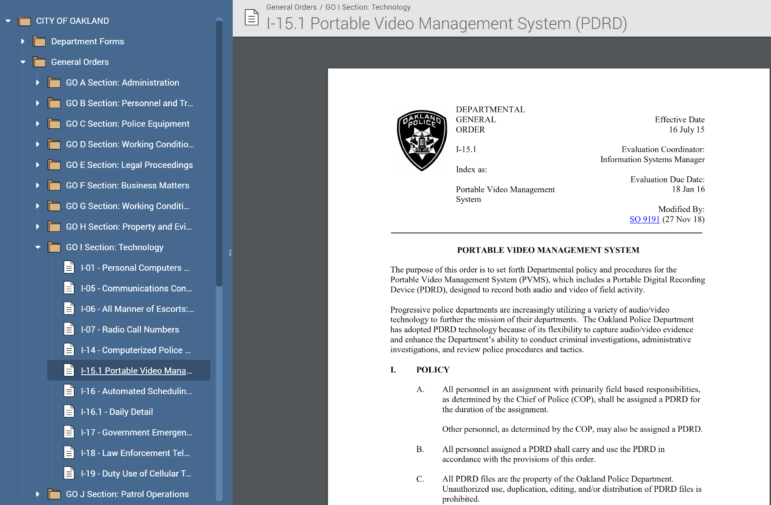

But 16 agencies sectioned their manuals into separate PDF documents and published links to each section. This requires an outsider to correctly guess which section to open for searches, and ultimately results in repetitive searches across all the published sections. In order to view the Oakland Police Department’s policy on body-worn-cameras, for example, a user must successfully navigate a hierarchy of folders and specialized headings.

The San Francisco Police Department, too, partitions its required publication. Meanwhile, San Francisco also has a Committee on Information Technology that is required by city ordinance to publish this page, which lists all of the surveillance technologies employed by all city departments. The committee’s list of technology used by SFPD is extensive but explicit and includes a reference to Pen-Link, a communications company that provides law enforcement agencies with technology that intercepts electronic communications. But we were unable to find any explanation of this technology in the SFPD’s policy publications, although we may have missed it in our manual search through its partitioned interface.

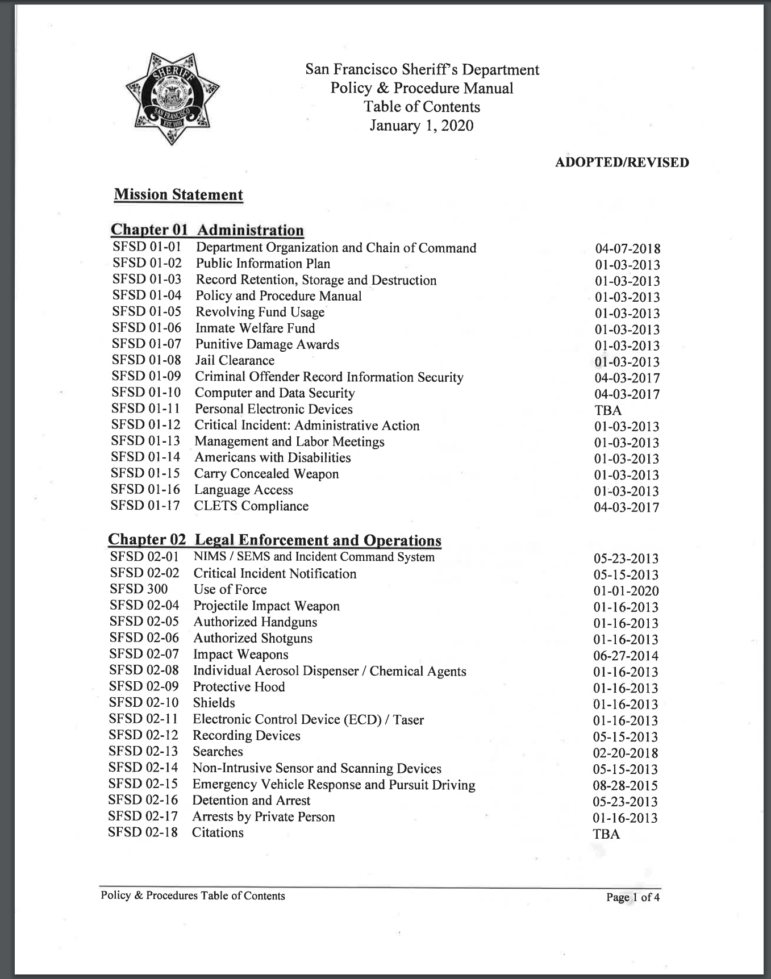

Oakland’s and Berkeley’s police publications are similarly arranged, and thus similarly opaque. The San Francisco Sheriff’s department is considerably worse. The Sheriff’s policies, pictured below, are both partitioned and stored as scanned and non-searchable images without an index or table of contents, thus requiring any researcher to manually scan more than 650 pages of content.

We have criticized law enforcement agencies from San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley for how they have complied with Senate Bill 978 because these agencies could easily clarify how they’ve presented their policies to their communities.

For greater trust and accountability, police departments that rely on surveillance camera footage should articulate how their officers obtain that footage, how they use it, and who gets access. Furthermore, we recommend that all agencies publish their policies in a way that an uninitiated outsider can navigate. These are simple revisions that might bring greater accountability and trust to about 1.5 million Bay Area citizens.

Shelby Perkins and Craig Nelson are graduate students at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute, where they study international policy. The views expressed here are their own.