San Francisco’s housing and homelessness service providers worry that City Hall’s budget decisions will leave them unprepared to face an expected wave of housing displacement.

Interviews with staffers at a dozen nonprofits found that calls for assistance have increased by at least 30% and at some organizations by as much as 200% since March when the pandemic forced San Francisco residents to shelter in place amid a recession characterized by widespread income loss. Many providers are concerned expected city budget cuts will hobble their ability to provide vital aid like rental assistance, legal representation in eviction cases, food and emergency shelter, just when clients need help the most.

One likely outcome of expected cutbacks they predicted: a worsening of the city’s already daunting homelessness crisis.

“We’re all bracing ourselves for a huge growth in the numbers of those who are living on the streets, no question,” said Sara Shortt, director of public policy and community outreach at the Community Housing Partnership, a supportive housing nonprofit. “Most of us walk down our streets and see so many people currently in tents or otherwise. To imagine that number getting bigger without the resources to address it is really scary and sad.”

Mayor London Breed is slated to present a two-year citywide budget Friday, which will attempt to close a $1.5 billion deficit. Negotiations must result in a final budget by an October 1 deadline. Breed previously said budgets for the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing and the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, which heavily fund many nonprofits, should shrink by between 10% and 15%.

A ‘perfect storm’ for nonprofits

Homelessness was on the rise in California before the pandemic, and a recent Columbia University study predicts a 20% increase this year over 2019 as economic hardships from the coronavirus sweep the state. The wave will hit San Francisco especially hard thanks to a dearth of affordable housing in the city, several service providers said, especially if the programs that help people avoid or exit homelessness see their budgets shrink.

Homelessness disproportionately affects Black and brown communities, and the proposed cuts would hit them hardest, said Joe Wilson, executive director of Hospitality House homeless shelter and resource center. Combined, these factors have created “a perfect storm for our homelessness system,” Wilson said.

“Cutting services for agencies that service these communities is inequitable,” he said. “We cannot cut our way out of this crisis; we have to build our way out of it.”

Hospitality House relies heavily on public funding and has already suspended a move-in assistance fund for people exiting homelessness. Wilson anticipates staff or program cuts if funding is slashed much further.

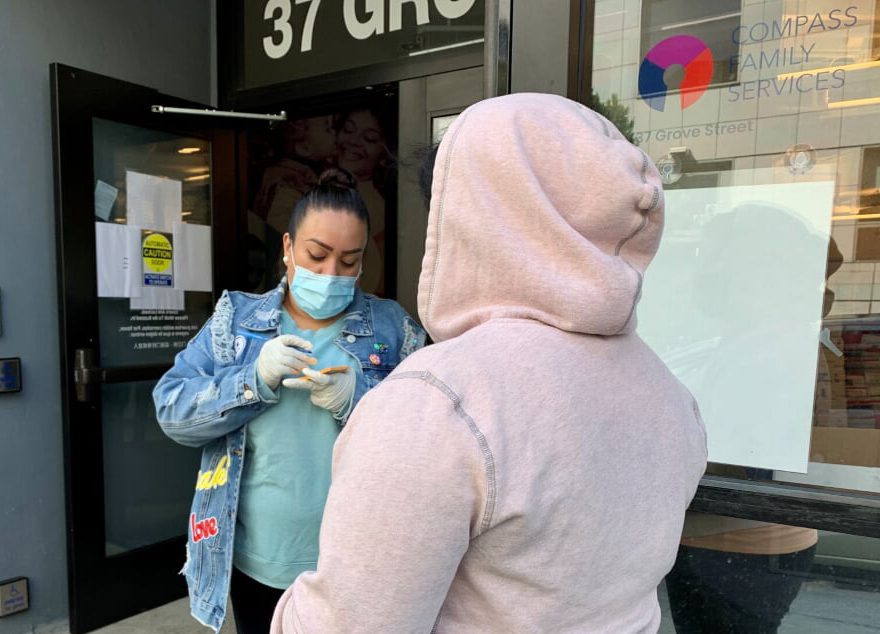

Courtesy Mary Kate Bacalao

Bilingual therapist Amber Tibbitts (left) greets a family member at Compass Family Services’ resource center for unhoused families. The nonprofit has stepped up fundraising efforts as demand for resources spikes.In response to the city’s proposed cuts, a collective of service providers co-chaired by Wilson asked Breed on July 27 for more than $42.5 million to fund hundreds of housing subsidies, a job training program and a safe injection site for unhoused drug users. The proposal would also preserve programs that could otherwise fall under the budget knife: a family homeless shelter, a long-term housing subsidy program for families and two legal advocacy programs for homeless clients.

Swords to Plowshares and its partner group, the Homeless Advocacy Project, pair lawyers with more than 400 unhoused people each year, helping them secure veteran’s benefits, social security and food stamps, said Maureen “Mo” Siedor, legal director at Swords to Plowshares. Many of the two programs’ clients are disabled, Black, veterans or over the age of 50, Siedor said.

“There’s not another legal service that does this work,” she said, adding that she’s unsure what the two nonprofits will do if they lose city funding. “Ethically, we can’t just bow out, but even if we had to, there’s not another place we can send these clients. They don’t have another option.”

When asked how the homelessness department was preparing to handle a spike in unhoused residents, a department representative did not directly answer the question, saying it has been “actively engaged with our non-profit and City partners in the collaborative efforts to prepare for and respond to the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) since February.”

No legal defense for 250 eviction cases

Breed this week extended San Francisco’s eviction moratorium to end Oct. 30. If she does not extend it again, landlords could try to evict tenants in November for lapsed rents due that month, said Martina Cucullu Lim, executive director at the Eviction Defense Collaborative. In addition to rent assistance, the nonprofit’s staff administers the city’s Right to Counsel program, a voter-approved initiative that guarantees free legal representation to residents facing eviction.

Cucullu Lim worries that overworked attorneys won’t be able to take on the additional cases when the moratorium lifts. “Right now, the system is taxed,” she said. “If we knew that we could hire another attorney, we would be hiring immediately. And that person would be able to provide services now.”

Instead of staffing up, the collaborative and the eight other organizations that provide free representation have five attorney positions that lie vacant due to budget shortfalls. Cucullu Lim is waiting to see if City Hall steps in to fill those funding gaps. Should those roles be filled, each person would handle about 50 cases per year.

“We thought tenants were in desperate straits before the pandemic in San Francisco, and displacement was dire. We’re about to see something we’ve never seen, in the number of people moving out because they don’t understand their rights.”

Sarah Sherburn-Zimmer, Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco

City departments have given nonprofits limited funds to hold them over during the budget negotiation process, which will determine total outlays.

The Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development has committed $1.58 million to the collaborative for fiscal year 2020-2021 — about 35% of what it received last year. Cucullu Lim has downsized her staff because she is uncertain whether more money is coming.

“We had to lay off the attorney that was dedicated to our intake legal clinic,” she said. That person had helped clients defend themselves as an alternative to providing full representation. The collaborative has two other vacant positions and recently rescinded a job offer to a social worker, who would have enabled the attorneys to better focus on their legal work.

Fewer tenants knowing their rights

The Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco and two other organizations will be able to make fewer calls to tenants to educate them about their rights, thanks to a cut of nearly $100,000 to a city grant, said Sarah Sherbern-Zimmer, the committee’s executive director.

“It literally means that we are furloughing or not hiring counselors,” Sherbern-Zimmer said, adding that layoffs could be the next step. “So that means you might wait days to get someone to call you back.”

The city’s stopgap funding has left a “devastating” $320,000 hole in the organization’s budget for fiscal 2020-2021, compared with what City Hall funded last year, and it is unclear whether more money will come, Sherbern-Zimmer said. That money would pay for outreach and organizing in public housing; help for tenants in negotiating for proper living conditions; counseling in five languages to people in rent-controlled buildings; and training other nonprofits on tenant rights.

Those services are more important than ever, Sherbern-Zimmer said. The Board of Supervisors, Breed and Gov. Gavin Newsom have all declared eviction restrictions with slightly different timelines and stipulations. Tenants who struggle to understand their rights are more vulnerable to landlord attempts to push them out.

“The pain is more than dollars and cents or abstract accounting entries. It’s real people, real lives, real harm. It is emotional violence — killing our souls, cutting out the heart of our humanity.

Joe Wilson, Hospitality House

“We thought tenants were in desperate straits before the pandemic in San Francisco, and displacement was dire,” Sherbern-Zimmer said. “We’re about to see something we’ve never seen, in the number of people moving out because they don’t understand their rights.”

Tenants are facing situations that are “all over the map,” said Tommi Avicolli Mecca, director of counseling for the Housing Rights Committee.

He recounted what he’s heard: “Landlords saying I have to pay,” “It doesn’t matter what the mayor’s order is,” “Landlord is giving me a hard-luck story, and if he doesn’t get paid then he’s going to have to sell the building.” Summing up, he said, There’s no one story.”

Need for services on the rise

Service providers have already seen their clients’ needs grow.

The Eviction Defense Collaborative has seen elevated demand for rent assistance since the pandemic began. At the Housing Rights Committee, compared with pre-coronavirus levels, overall calls are up 50% and those from primarily Spanish speakers are up 200%, Sherbern-Zimmer said.

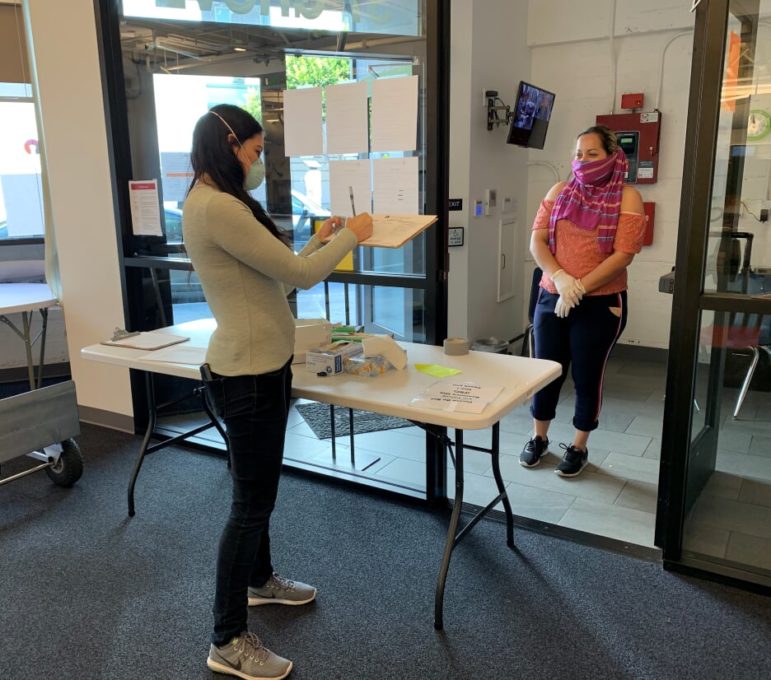

Since March, Compass Family Services has served an average of 40% more clients per month than in the months preceding the pandemic, much of that increase is a result of the tumbling economy, said Mary Kate Bacalao, director of external affairs and policy at Compass Family Services, a resource center and shelter for unhoused families.

“With so many drop-in centers either closing or reducing capacity, we have lines every day for people wanting to get in, seeking temporary refuge,” Joe Wilson said. He estimated that demand for Hospitality House services has risen 25 to 30% since the pandemic began. The bulk of requests are for basic needs like food, diapers or help finding work, several service providers said.

Nonprofits like Compass and Hospitality House have increased their fundraising efforts in an attempt to meet the demand. Compared with public funds, private donations have fewer strings attached so service providers can use them creatively in a pinch, Bacalao said. But public funds are many of these organizations’ lifelines, and the prospect of having to serve more people with reduced funding and fewer programs in their network is daunting, Bacalao said.

“We’re awake at night worrying about these families and worrying about the needs across the city,” she said. “It’s not just Compass, it’s all of our partners. It’s an extremely stressful time for all of us.”

Budget cuts are just one of the nightmares keeping up service providers at night, Wilson said. To see people facing eviction, sleeping in tents or struggling to feed themselves during a deadly pandemic every day takes a toll on nonprofit workers, he said.

“The pain is more than dollars and cents or abstract accounting entries,” Wilson said. “It’s real people, real lives, real harm. It is emotional violence — killing our souls, cutting out the heart of our humanity.”

CORRECTIONS: Captions for the photographs of Mariela Esquivel and Amber Tibbitts were switched in a previous version of this story; they are now correct. Corrects statement about Swords to Plowshares and Homeless Advocacy Project client base to reflect that many of the groups’ clients are disabled, Black, veterans or over age 50.