On Jan. 8, 2020, Jayson Hill awoke in his tent near Jerrold Avenue and Rankin Street in the Bayview to the voices of police officers informing him he had to leave his camp.

“Imagine you are at home with your family when there is a knock at the door,” Hill recalled to Judge Michelle Tong in an August small claims hearing. “It is the police and they do not look happy to see you. You are taken to the end of the road and told to wait; and for the next hour while the officers wait for the bulldozers to come, they threaten you any time you ask to be allowed to retrieve your medication or food for your animals, or at least warmer clothing.”

That morning Hill lost everything. The Department of Public Works deployed a bulldozer and cleaning crew that decimated his camp. It was one of hundreds of cleanup operations the city has conducted since launching its Healthy Streets Operation Center — a multi-departmental agency tasked with relocating large homeless camps — in 2018.

On Thursday, a damning report dropped, offering new data on San Francisco’s practice of sweeping encampments. Authored by the Coalition on Homelessness, the report alleges the Healthy Streets Operation Center regularly fails to offer an adequate number of shelter beds to people on the streets during its cleanup operations and is illegally discarding people’s belongings.

The practices create serious legal risk for San Francisco. After connecting with the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area, Hill and nine of his neighbors successfully sued the San Francisco Department of Public Works over a lack of notice ahead of the cleanup. In August, Tong awarded each defendant $10,000. The city appealed on Oct. 1.

“They are taking enforcement action without sufficient shelter to offer people,” said Elisa Della-Piana, the Committee’s legal director. “They are not following their own policies and are destroying belongings instead of saving them for people to reclaim. We’re hearing that people aren’t getting proper notice of the sweeps, that they’re finding out the morning of that crews are arriving, and not having sufficient time to move their things.”

According to Della-Piana, those actions violate Martin v. Boise, which requires cities to have adequate shelter beds available before conducting anti-camping measures, as well as being unconstitutional. The Fourth Amendment prohibits seizures of belongings, and the Fourteenth Amendment requires due process, such as a notice before a cleanup begins.

Shelter Beds in Short Supply

The Healthy Streets Operation Center is made up of staff from the Department of Emergency Management, the Police Department, the Department of Public Works, the Department of Public Health, and the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. The task it faces is gargantuan: clearing hundreds of homeless camps from public spaces.

In the year ending in June 2021, the Center cleared 79 homeless camps where 4,648 people lived. About 45% of those people accepted offers of shelter, according to a presentation from the Department of Emergency Management.

The Coalition’s report offers a closer look at that number and shows the acceptance rate has fluctuated enormously. In July 2020, when shelter-in-place hotel rooms were still available to people experiencing homelessness, 83% of the 816 people encountered during sweeps chose to move indoors, the report showed. By mid-December, when the shelter-in-place hotels had stopped accepting new intakes and group shelter was being offered, only 30% of the 854 people swept took those placements.

But even if everyone at the homeless camps agreed to congregate shelter, where multiple people share a room full of beds, the city simply doesn’t have enough spaces to offer people.

“We can’t do Healthy Streets Operations Center work without having shelter resources,” Department of Emergency Management Director Mary Ellen Carroll said during an Aug. 2 meeting of the Local Homeless Coordinating Board. “It is the most important tool that we have, and it is necessary for us to have adequate resources for us to do that work.”

Carroll notes that the Center uses a formula to determine how many shelter beds are needed during each operation and that if there aren’t enough, the sweep won’t move forward. “We use the formula that we use based on our experience to know how much resources we do need when we go to do a resolution,” she said during the August meeting.

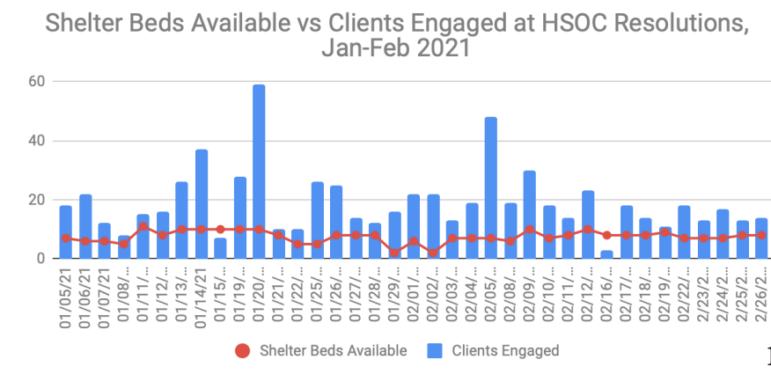

That formula appears to result in offering shelter beds to only 30-40% of an encampment’s population. In the seven weeks ending Feb. 22, 2021, only four shelter beds were available for every 10 people the Healthy Streets Operation Center interacted with. In that period, 712 people were swept from their camps, but only 277 beds were offered.

Courtesy Coalition on Homelessness / Courtesy Coalition on Homelessness

Sam Dodge, the newly appointed director of the Healthy Streets Operation Center, told the San Francisco Public Press that the formula changes each week, and at the moment teams head out with enough shelter beds available for around 40% of any encampment. “That’s the minimum, that’s what you start with,” he explained. “If the team happens to be in a place where there’s a lot of acceptance and not a lot of shelter beds, they stop and come back the next day.”

Lost Belongings

In addition to providing homeless people with shelter, the city cannot seize belongings unless they’re unattended, and under its own policies, must store any items for 90 days to give residents a chance to reclaim them.

But data from the Coalition’s report shows a serious discrepancy between the “bag and tag” log from the Department of Public Works, which stores the unattended belongings, and the dates that the Healthy Streets Operation Center conducted its encampment cleanups.

When cross-referencing the addresses where cleanups happened in January and February with the bag and tag logs from Public Works, there were zero overlaps. Not a single item from the 712 people the Center interacted with in those two months was taken to the Public Works’ yard for storage, according to the data.

It’s this seizure of belongings that ultimately secured Hill and his nine neighbors $100,000 in their settlement against Public Works. Hill and his partner, Nichelle Solis, another plaintiff in the claim against Public Works, lost work clothes, books, artwork and sentimental heirlooms — a scarf Hill’s grandmother crocheted for him, and his family Bible.

“When you’re out on the street people look at you differently and treat you differently,” he told the San Francisco Public Press over the phone on Wednesday. “When you’re out there, in a tent or a box, some of the things that you used to have in your old life make you feel a little bit grounded, more human. If there’s a tidal wave coming you might grab something you don’t need for survival, but that will remind you that once you were once someone other than a vagrant. Those are the things we were stripped of.”

Della-Piana, the lawyer who helped Hill file his suit, said there are many more small claims like this that could be filed — but it’s not easy keeping track of plaintiffs when they have no fixed address.

“One of the biggest barriers to filing these claims is repeated sweeps,” she said. “The very action people are harmed by is preventing them from being able to correct the injustice. If you’re constantly moved around, you can’t get your footing.”

After their tent and belongings were bulldozed, Hill and Solis spent much of 2020 — in the heat of the pandemic —bouncing around between congregate shelters. They finally got into permanent supportive housing, but the rest of the camp at Jerrold Avenue and Rankin Street weren’t so lucky. Many are still outdoors, and one fellow plaintiff, Edward Richardson, died on the streets a couple of months ago, after the judge’s ruling.

Hill says he wishes there was more focus on services during sweeps and believes the city is to blame for Richardson’s death. “Every death that happens outdoors due to pneumonia, or drug overdose, or exposure, or hunger, or thirst, anyone who dies outside like that, their blood is on the hands of the people who could have helped them,” he said.