Extreme weather events in recent years have caused immense devastation and loss of life. In 2022, heatwaves in Europe and floods in South Asia and West and Central Africa killed thousands of people. This year, wildfires in Maui, one of the deadliest on record in the United States, claimed 100 lives. And wildfires in Canada displaced thousands and prompted U.S. agencies to issue air-quality health advisories for more than 120 million people.

While these kinds of disasters wreak havoc across all populations, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warns that some people, including older adults, are at heightened risk due to pre-existing conditions, weakened immune systems, restricted mobility and other health challenges.

San Francisco has already seen extreme weather conditions threaten the well-being of older residents, especially in neighborhoods like Chinatown, which city analysis has shown is particularly vulnerable to these threats.

In the past several years, smoke from wildfires and rainstorms have caused health and other problems for Chinatown’s older residents. Community organizations worry that the systems in place in the neighborhood are not enough to protect older populations, in part because of the challenges of accessing climate-resiliency funding.

“Climate change definitely affects our seniors’ quality of life as well as their health,” said Anni Chung, president and chief executive officer of Self-Help for the Elderly, a nonprofit providing an array of services for older adults in Chinatown and beyond since 1966.

Shao Ao Situ, an 81-year-old tenant of a single-room occupancy building in Chinatown, said he experienced eye irritation, fatigue and coughing when smoke from wildfires that raged across California and the Pacific Northwest in 2020 drifted through his neighborhood.

As COVID-19 was taking a disproportionate toll on older adults that year, the skies above the western United States turned an eerie orange, and the air filled with ash and toxic particles.

“I was severely affected,” said Situ, who speaks Taishanese and Cantonese.

Residential rooms in Situ’s building are dense and compact, measuring about 8 by 10 feet. A bunk bed, a table, a dresser and shelves take up most of Situ’s space, leaving little room to walk. His clothes hang over a single, long window. When smoke covered San Francisco that year, he said, he drew the window almost all the way down, allowing a small gap for ventilation.

“When the smoke concentration from the wildfires was high, I felt discomfort in my throat when breathing,” he said. Situ said his cough made it difficult for him to sleep at night. He looked for resources to cope with the situation.

“I heard on TV that N-95 masks are the best at preventing dust and pollution particles, so we bought two boxes at that time,” Situ said, adding that government and community groups should provide more direct education to older people on how to stay safe.

He said his health problems persisted even after the smoke subsided.

[See photo essay: “For Chinatown’s Older Residents in SROs, Climate Disasters Pose Greater Risks”]

There are around 193,800 residents in San Francisco who are 60 and older. From 2010 to 2060, the city expects to see a 159% surge in its 60-plus population, according to the California Department of Aging. Meanwhile, the frequency and intensity of climate change-driven weather disasters are expected to increase.

Climate and health hardships that older residents like Situ in Chinatown and those in other parts of the city have confronted and will encounter in years to come have been on the city’s radar for over a decade.

In 2010, San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was one of the first agencies in the nation to launch a program to investigate climate change’s effects on the health of residents and draw up contingency plans.

Since then, detailed assessments conducted by the department in collaboration with other agencies have outlined numerous health impacts San Francisco neighborhoods could face from air pollution, heatwaves, wildfire smoke, flooding and other hazards. Those reports noted that besides Chinatown, Bayview-Hunters Point, South of Market, Civic Center and Visitacion Valley could bear the brunt of the climate crisis.

In a system the department developed to gauge each neighborhood’s climate resiliency, Chinatown received the lowest overall score. “The elderly residents of Chinatown are especially at risk due to the neighborhood’s high residential density, overcrowded living conditions, and urban heat island vulnerability,” the department’s environmental health experts wrote in a report published in 2014.

The climate resiliency scorecard for Chinatown developed by San Francisco’s Department of Public Health.

Hidden health harms

Kinchiu Fung, 65, lives in a single-room occupancy building in Chinatown. Fung said his breathing was affected when wildfire smoke cloaked San Francisco in 2020. He said he was able to manage on his own. But some of his older neighbors expressed concerns about leaving the building during extreme weather, he said.

“The government should help the elderly if it has resources,” said Fung, who speaks Taishanese and Cantonese. He said more volunteers are needed to help older tenants with limited mobility during rainstorms.

Bifang Kuang, 84, who lives in a single-room occupancy unit in Chinatown, said she stayed in her room during torrential rainfall that pelted the Bay Area last January. “I did not get my medicine when it was raining,” said Kuang, who primarily speaks Taishanese.

Ambika Kandasamy / San Francisco Public Press

Bifang Kuang, 84, says she is unable to get her medications during heavy rainfall.Supplementing the city’s research into how climate change impacts health, universities across the Bay Area are examining both obvious and subtle impacts of extreme weather.

During heavy rainfall, older adults could break a hip or long bone if they slip on sidewalks, and the steep slopes of Chinatown and other hilly neighborhoods could worsen the impact, said Dr. Andrew Chang, a cardiologist and fellow at the University of California San Francisco’s Advanced Echocardiography program.

Extreme weather events can also affect diet. Some older adults who live alone and cannot obtain fresh fruits and vegetables during severe weather might turn to pantry staples or frozen foods that are high in salt, fat, oil and processed sugar, Chang said. Because older adults tend to have pre-existing conditions that make their bodies sensitive to sodium load, consuming salt-heavy products could trigger heart failure, high blood pressure or fluid retention, he said.

Weihong Wu, 53, lives with her husband in a single-room occupancy building in Chinatown. During the 2020 wildfire season, she said, if she opened the window, she didn’t feel well, and if she didn’t open the window, the room became too stuffy. “It’s like, we can’t breathe,” said Wu, who speaks Taishanese and Cantonese.

“No one knocked on our door and asked if we are OK,” she said.

Wu said that during the rainstorms earlier this year, she couldn’t go out, so she didn’t have any food in her home. She said her older neighbors in the building “really needed someone to deliver groceries to them because they are unable to go grocery shopping themselves.”

Inclement weather can also deter people from seeking medical care. “Not only people who are getting sick from air pollution, but also people who probably normally should be seeing the doctor or getting medical care for certain conditions are choosing not to go be seen because they don’t want to go out when it looks so frightful outside,” Chang said.

Another concern in single-room occupancy residences and other older buildings is accessibility.

In 2022, San Francisco’s Aging and Disability Affordable Housing Needs Assessment highlighted accessibility problems like steep stairs and malfunctioning elevators in the city’s publicly funded single-room occupancy housing stock.

Compromised access intensifies risks for older residents in those buildings. For example, tenants experiencing exhaustion or other symptoms from excess heat or wildfire smoke might struggle to walk down several flights of steep stairs to reach a cooling or air respite center.

Ambika Kandasamy / San Francisco Public Press

A single-room occupancy residence on Clay Street in Chinatown has steep stairs, no elevator and a single wheelchair ramp on the first floor.Housing experts say people who experience such health or mobility challenges should have a say in what would help them most.

“I think you need to engage the seniors themselves,” said Leslie Moldow, a principal at Perkins Eastman architectural firm, where she specializes in senior living design, and an adjunct professor at the University of San Francisco. “Have them be part of the solution for what they want.”

Financial barriers

In 2021, Mayor London Breed released the latest iteration of the city’s Climate Action Plan with an overarching goal for San Francisco to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040. While the plan focuses on emission reductions, it also emphasizes related health benefits, noting that walking and biking boost physical well-being, green spaces improve air quality and eradicating fossil fuel use in buildings protects against chronic ailments like asthma.

Breed this year announced $2 million in grants for organizations working on removal of greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, waste prevention and environmental justice. But many of the plan’s long-term goals come with sky-high costs, and officials say San Francisco can’t go it alone.

“External support, from state and federal governments, is needed more than ever,” city officials wrote in the Climate Action Plan.

A funding analysis for the Climate Action Plan by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment, estimated that the overall cost of reducing emissions across sectors that the plan targets could reach $22 billion.

The financial analysis of San Francisco’s Climate Action Plan prepared by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley.

That analysis is used “to make a case that much more funding will be needed in the future to fully implement the plan” said Richard Chien, senior environmental specialist at the San Francisco Department of the Environment.

Louise Bedsworth, the executive director of UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment, is one of the authors of the funding analysis. Bedsworth said her team is exploring the barriers to moving projects from planning to implementation.

“I think funding remains the biggest challenge,” she said, partly because the way funds for climate adaptation are distributed is compartmentalized.

“People don’t live in silos, and communities don’t operate in silos,” she said. “But that tends to be how our funding is still rolled out.”

In July, San Francisco released a Heat and Air Quality Resilience Plan, which proposed pathways for city agencies, community groups and other stakeholders to help San Franciscans cope with extreme heat and wildfire smoke.

Officials noted in the report that $12.1 billion in federal funding is available for home energy efficiency and weatherization projects through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. And $444 million is devoted in California’s budget this year to extreme heat mitigation initiatives. This is in addition to funding available from other government and private grants and programs.

Bedsworth said one of the challenges for small nonprofits in accessing funds from state programs and the federal Inflation Reduction Act is the complex and competitive nature of these initiatives.

The Chinatown Community Development Center, which owns and manages single-room occupancy buildings and other affordable housing, faces such hurdles. Nearly 1,900 seniors live in properties managed by the organization.

For years, the nonprofit, which also engages in tenant advocacy, youth leadership and other community work, has tried to improve the sustainability of its buildings and the Chinatown neighborhood. It has worked with local nonprofits to provide some tenants with climate-resiliency tools such as air filtration devices.

Malcolm Yeung, the center’s executive director, said the resources in Chinatown are “absolutely not” sufficient to support older adults in single-room occupancy housing during extreme weather events, adding, “But it’s not to say that there aren’t efforts underway.”

In 2017, the organization, in collaboration with San Francisco’s Department of the Environment, Planning Department and philanthropic groups, published a comprehensive assessment called “Sustainable Chinatown” that laid out strategies for improving sustainability and climate-resiliency while maintaining housing affordability.

Yeung called it a “mixed success.” Some goals were met, but others stalled for lack of funding, he said. The organization has explored creative approaches to make sustainability improvements that are less resource-intensive.

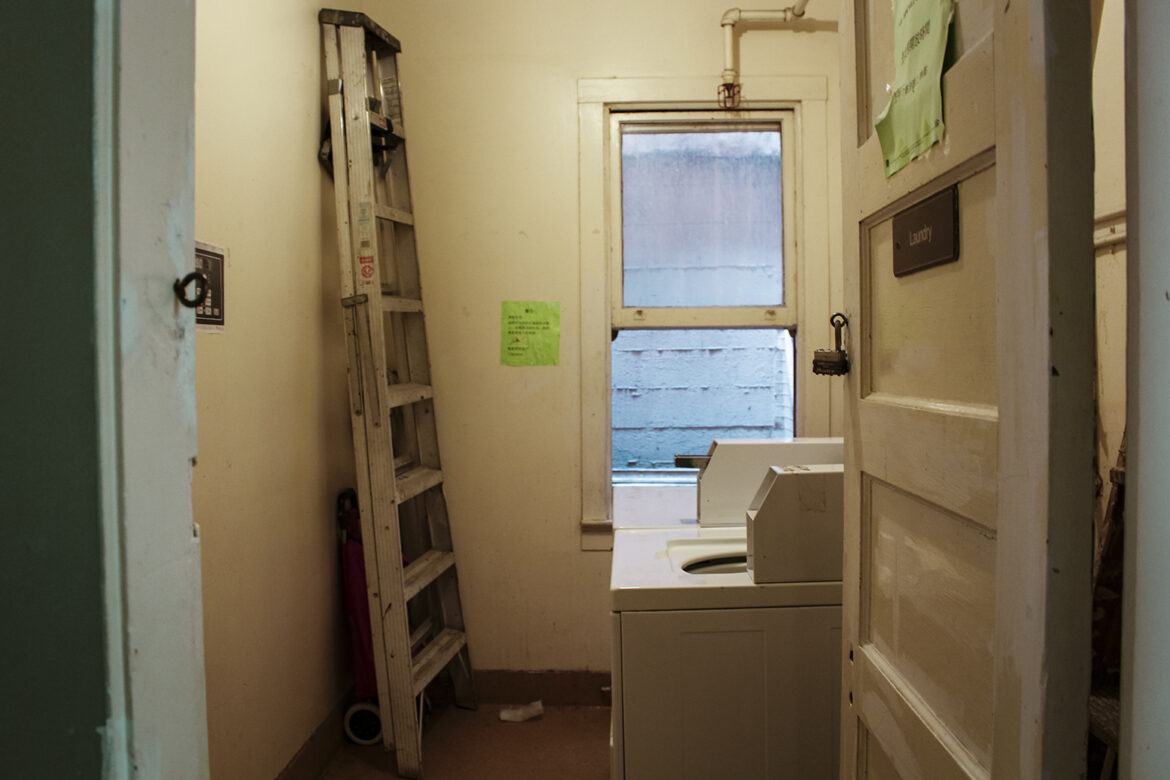

For example, when it was taking over public housing from the city’s Housing Authority to rehab and operate as affordable housing, staffers saw that tenants had installed unauthorized, energy-draining washing machines and clothes dryers, because they feared robberies and violence in communal laundromats in their building. The nonprofit removed the appliances, bolstered security and implemented community policing in collaboration with the San Francisco Police Department to alleviate residents’ concerns, he said.

That was “the single largest sustainability improvement in that building, and it was primarily because of operating changes,” Yeung said.

Ambika Kandasamy / San Francisco Public Press

The laundry room in one of Chinatown Community Development Center’s single room-occupancy buildings is available for tenants.Yeung said whenever his organization is rehabilitating or constructing a building, it works with sustainability consultants to identify ways to improve operating efficiency and climate resiliency. However, finding funding for those upgrades, he said, is a hit-and-miss process.

The Chinatown Community Development Center sees the Inflation Reduction Act as a potential funding source to complete upgrades systematically. “We have not secured funds, but the initial process is rolling,” Yeung wrote in an email.

A number of large affordable housing and climate justice intermediary organizations are submitting applications to distribute funds through the act’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, Yeung said. The Chinatown Community Development Center has shared its sustainable rehabilitation recommendations with three of those applicants.

Yeung echoed Bedsworth’s earlier point that smaller organizations struggle with navigating the complexities associated with applying for this kind of federal funding.

“Communities of color typically don’t have anchor organizations that have the resources to kind of engage on that level,” Yeung said.

Policies determining funding

San Francisco has 110 publicly funded single-room occupancy buildings. Many others are operated by private owners or other entities. There are at least 19,000 rooms for tenants overall. Residents typically share a kitchen, living area, bathrooms and laundry facilities.

Many of the buildings don’t have cooling systems, adequate insulation and ventilation, or other mechanisms to cope with extreme weather.

The Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development oversees 1,021 affordable housing units in Chinatown that are managed by three organizations, including the Chinatown Community Development Center. Data for 942 households supplied to the agency revealed that 519, or 55%, have at least one senior tenant, the department reported.

“Seniors and SRO families are probably the two populations I worry a ton about because the vulnerabilities are very unique for each,” said Eddie Ahn, executive director of Brightline Defense, an environmental justice nonprofit.

Brightline Defense, in collaboration with its community partners, surveyed residents of single-room occupancy buildings in the city in 2020 and 2021. Of the 255 people across 54 buildings who responded, around 79% did not have access to N-95 masks and 73% did not have air filtration systems in their rooms. More than half the respondents said they had respiratory or other health effects during the wildfires.

Ahn, who is also president of San Francisco’s Commission on the Environment, said Brightline Defense worked with the Chinatown Community Development Center a few years ago to distribute about 100 air filtration units in Chinatown, the Tenderloin and other neighborhoods.

“But it only goes so far,” he said. “Part of the reason why our nonprofit exists is to affect policy change. It’s not just about, you know, 50 units here, 100 units there; it’s hopefully trying to increase access to thousands of units at a time.”

One policy the organization is focusing on involves CalEnviroScreen, a mapping tool that uses environment, health, socioeconomic and other data to determine which census tracts are most affected by pollution and other environmental hazards, and classifies those areas as “disadvantaged communities.” The California Environmental Protection Agency and other entities use it to determine where to implement programs and target investment. According to the tool’s standards, Chinatown is not designated as a “disadvantaged community,” which Ahn considers an incorrect assessment.

“It’s very clear that there’s a history of incidents in Chinatown and in the Mission District to have racial discrimination, disinvestment,” he said. “And overall, there are unique environmental injustices that are being suffered in each community, too.”

Ahn said his organization filed an advocacy letter with other community organizations, calling for improvements to the CalEnviroScreen tool.

“Population characteristics including poverty, housing burden, education and especially linguistic isolation exceed the 99th percentile in all of Chinatown’s census tracts,” wrote the letter’s signers. “Chinatown also suffers from serious pollution burdens.”

Letter sent by a coalition of nonprofits, calling for Chinatown to be recognized as a community needing investment by the CalEnviroScreen mapping tool.

Brightline Defense has installed monitoring sensors to gather neighborhood-level data on air pollution.

“So, if you have massive climate change events like wildfires, for instance, that are pouring smoke into cities, our most vulnerable are low-income households and families that can’t afford an air filtration unit,” Ahn said. “And that is typically an SRO tenant, for instance, or an SRO family. So, that’s the kind of targeting I think we need to demand of our environmental justice mapping tools.”

Community response

One nonprofit at the forefront of disaster preparedness for Chinatown residents, including older adults, is the NICOS Chinese Health Coalition.

Michael Liao, director of programs, said NICOS coordinates with community organizations to do periodic resource inventories to assess which groups can offer cooking facilities, emergency shelters, communication tools, transportation supplies and other resources during climate-related emergencies and other catastrophes.

“Over the years, we’ve also developed emergency communication protocols with multiple layers of redundancies, so that we could communicate with each other before the city is able to effectively and adequately respond to all of our needs,” he said.

In the past, the disaster preparedness initiative’s funding has come mostly from private foundations, like the Fritz Institute and the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Liao wrote in an email. During his 18 years at NICOS, he said, the initiative has received government funding from San Francisco once and from California once. Apart from those times, it has continued either unfunded or covered through the organization’s unrestricted funds, he said.

“Although the government regularly touts us — Chinatown — as a neighborhood, that is one of the most prepared, there hasn’t been a lot of investment, in terms of financial investment, to kind of help make that happen,” Liao said. “It really came from a lot of sweat, blood and tears from volunteers of the community who were able to put in their time and resources.”

Liao said the neighborhood’s support systems were weakened during the pandemic. “Funding is always an issue, and now even more so than before,” he said.

Self-Help for the Elderly is also pursuing climate-resiliency interventions for older residents. This year, through the city’s Extreme Weather Resilience Program, an initiative by the Department of Emergency Management, the nonprofit and other groups will receive devices like air filters and portable air conditioners. “That’s really good news,” said Chung, who leads Self-Help for the Elderly, noting that her nonprofit will use the items in its senior centers.

But more systemic solutions are needed, Chung said: “We’re doing only a patch-up here, like a band-aid right now.”

On Lok, which pioneered the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, also provides medical and social services to low-income older adults in Chinatown and beyond. It offers comprehensive services by combining primary health care and long-term care, so members with chronic illnesses or other conditions who might otherwise have to move to a nursing home can remain at home, said Dr. Ben Lui, the organization’s chief medical officer.

When climate disasters happen, Lui said, On Lok can activate its network of social workers, drivers and others to check in on its members. On Lok also helps operate federally funded housing for older residents.

For residents in those housing units, “we can actually do even closer monitoring, so we can even have our caregivers check on them to make sure they have the windows open during hot weather,” he said. “We can make sure that they are hydrated.”

Lui said the organization groups members by health risk, “so that when disasters or these extreme weather events happen, we can start with the highest-priority,” he said.

City response

Various city departments have initiated programs, sometimes working with community-based groups, to support older adults and other vulnerable populations during extreme weather.

“I think that we are more prepared now than we were in 2020,” said Adrienne Bechelli, the deputy director of San Francisco’s Department of Emergency Management. “In 2020, we were more prepared then than we were in 2017, when we had our first major heatwave over that Labor Day weekend.”

San Francisco considers anything above 85 degrees to be an extreme heat event, and during Labor Day weekend in 2017, temperatures soared to 106, which likely led to the deaths of three older residents.

Even before the 2017 heat wave, there were indications that San Franciscans could be particularly susceptible to this threat. A study examining a 2006 California heat wave found that emergency department visits and hospitalizations rose across the state. Researchers noted that children up to 4 years of age and people 65 and older were at highest risk.

“This pattern suggests an important role for acclimatization and for factors related to the built environment,” researchers wrote in Environmental Health Perspectives. “In San Francisco, for example, housing stock is less likely to have central air conditioning both because of its age and because of the cooler climate.”

Bechelli said the city will face challenges in any kind of emergency response.

“I think that anyone who says, ‘We’re fully prepared and we’re ready to take on this hazard, no problem,’ is probably, unfortunately, mistaken,” she said.

The San Francisco Human Services Agency’s Department of Disability and Aging Services also manages care coordination for older adults, and during extreme weather events, staffers call high-risk residents to check for symptoms of dehydration, heat stroke and other medical emergencies, Joe Molica, the agency’s senior communications manager, wrote in an email. The department also shares safety information with community centers to broaden its reach, he added.

The San Francisco Department of Public Health’s Emergency Preparedness and Response team has worked with NICOS to offer trainings in English and Cantonese at health fairs in the Richmond neighborhood, Tal Quetone, the agency’s public relations officer, wrote in an email.

In the past four years, the team has worked with companies that manage single-room occupancy buildings in the South of Market neighborhood to offer training on climate change, he added. In one instance, it collaborated with other departments to research the impact of heat for a building managed by the John Stewart Co., which prompted the owner to buy air conditioners for all 98 units, Quetone wrote.

But these programs don’t cover all older adults who face health risks during extreme weather, and city officials said social isolation is a challenge. The Department of Public Health is exploring how to work on emergency preparedness messaging with specialists and organizations that support older adults.

“One of the things we’re looking at right now in the Heat and Air Quality Resilience project is how can we identify first points of contact for vulnerable populations,” which might include clinicians, residential caregivers and building managers, said Matt Wolff, the department’s Climate and Health Program manager.

Emotional ramifications

While researchers continue to study the consequences of extreme weather on the physical health of older adults, they are also looking into how it affects mental health. Clinicians with the Climate Psychiatry Alliance, a network of mental health professionals, say they have noticed post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and other mental health conditions among older adults, especially those whose lives have been upended by disasters like wildfires and floods.

Lila LaHood / San Francisco Public Press

Skies over San Francisco turned orange from smoke from wildfires in the western U.S. in 2020.For some older residents of Chinatown, the anti-Asian hate crimes that occurred concurrently with extreme weather and health emergencies intensified their emotional anguish.

“We were particularly concerned during the pandemic of this kind of triple-whammy effect for our Chinatown seniors with not only the pandemic but also a lot of the climate change-related issues such as extreme heat and air quality issues,” said NICOS’ Liao. “On top of that, a lot of seniors were afraid to go out because of the rise in anti-Asian hate.”

Liao said fears about anti-Asian hate crimes remain.

“As we come out of the pandemic into endemic for COVID, there’s still a lot of the lingering isolation, mental health and loneliness issues that our seniors struggle with,” he said.

Liao said NICOS conducted a focus group, part of a study funded by the National Institutes of Health, in partnership with the University of California, San Francisco, with Chinese seniors in single-room occupancy buildings to understand what might contribute to resilience. The organization found that some older residents were doing due diligence when it came to verifying health information they received on WeChat and other platforms. This also could be a critical step in protecting themselves during climate disasters when misinformation and disinformation can be rampant.

“I know a lot of times we focus on more of the negative aspects — what are some of the deficits and the needs — but I think it’s also important to highlight that within the Chinese community, there’s a lot of resilience,” Liao said.

Yesica Prado edited the photos for this story. Zhe Wu translated the interviews with residents in single-room occupancy housing in Chinatown who spoke Taishanese and Cantonese.

About the Project

Older adults are among those most at risk during climate change-driven weather disasters. This series examines the physical and mental health effects of these events on older people and explores how these challenges are unfolding in San Francisco’s Chinatown, a neighborhood considered by the city as particularly vulnerable to the hazards of climate change.

- Q&A with Dr. Andrew Chang on the physical toll of climate change on older adults

- Q&A with Dr. Robin Cooper on the emotional toll of climate change on older adults

- Q&A with Eddie Ahn on how Brightline Defense takes on air pollution and environmental justice concerns

- Long-form story: Protecting Chinatown’s Older Adults From Climate Change Disasters Requires More Funding, Nonprofits Say

- Photo essay: For Chinatown’s Older Residents in Single-Room Occupancy Buildings, Climate Disasters Pose Greater Risks

This project was produced with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, the Journalists Network on Generations and the Archstone Foundation.