Read the story by Mel Baker — “Return to Alcatraz: 50 Years After Native American Occupation, National Park Service Considers Permanent Cultural Center” — that accompanies this photo essay by Yesica Prado.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Alcatraz employees catch the first ferry of the day from Pier 33 in San Francisco. Onboard, everyone wears masks. Posters and floor stickers throughout the boat instruct passengers on COVID-19 guidelines. On June 15, California lifted mask mandates for most venues and allowed many businesses to set their own guidelines. But federal institutions, including national parks, continue to follow federal mandates.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Two National Park rangers wait on the dock before boarding a ferry to work on Alcatraz. In 1972, the federal government transferred the island to the Department of the Interior and the National Park system as part of the newly established Golden Gate National Recreation Area. That is when park rangers first became stewards of the island, which opened to the public for the first time the following year. Alcatraz is one of the country’s most popular national park sites. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it welcomed more than 1.5 million visitors annually.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Alcatraz’s natural features include rock pools and colonies of seabirds such as western gulls, cormorants and egrets. The 12-acre island’s structures include the oldest operating lighthouse on the West Coast, a decommissioned military outpost and the abandoned federal prison. In 1850, President Millard Fillmore signed an executive order to turn Alcatraz into a military fortress. It served as a military prison from 1857 to 1933, during which it housed prisoners of war, including Native Americans from American-Indian Wars.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

In 1933, the island was transferred to the U.S. Department of Justice and became a federal prison the following year. A yellow warning sign from that era on the agave trail cautions that visitors “concealing escape of prisoners are subject to prosecution and imprisonment.” The federal prison operated for 29 years, incarcerating a famous cast considered serious flight risks, including Al Capone, Robert Franklin Stroud (aka the “Birdman of Alcatraz”), George “Machine Gun” Kelly, Bumpy Johnson, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Mickey Cohen, Arthur R. “Doc” Barker and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, who served 26 years on Alcatraz –– longer than any other inmate. In 1963, the penitentiary closed, and in 1964, Alcatraz was declared surplus federal property. That is when Red Power activists first considered claiming the island, which they believed qualified by treaty for Native American land reclamation.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

On Nov. 20, 1969, about 80 young Native American activists, including some children, sailed to Alcatraz. Members of the group occupied the island for 19 months. At the height of the occupation, 400 people lived on Alcatraz. The activists formed a nonprofit named Indians of All Tribes and spoke out against the federal government’s termination policy — whereby Congress ordered tribes disbanded and their land sold — and other hardships endured by Native Americans. The occupiers used red paint to repurpose a penitentiary sign with a new message: “Indians Welcome. United Indian Property. Alcatraz Island. Area 12 acres. 1 ½ miles to transport dock. Allowed ashore without a pass. Indian Land.” “Occupying the island represented their ‘fight’ to live as free people in their own country,” occupation leader LaNada War Jack wrote in the Alcatraz Proposal, a document outlining the occupiers’ vision for the island.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

National Park employees arrive on Alcatraz to prepare the island for the day’s visitors. Masks and social distance guidelines are in place for employees and guests. Outdoors, visitors may remove masks within their own social groups. Federal Centers for Disease Control guidelines for parks and recreation facilities suggest continuing prevention measures to reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Occupiers painted political signs in red all around Alcatraz. As part of the 50th anniversary of the occupation, some of the original occupiers and their descendants repainted the faded messages across the island, including one on the water tower reading: “Peace and Freedom. Home of the Free. Welcome to Indian Land.” During the occupation, the U.S. government cut the water supply, electricity and telephone lines to Alcatraz. The occupiers brought in provisions on a boat named Clearwater. The occupiers said they wanted to bring attention to hardships they had endured on reservations, as well as those experienced when reservations were closed and later during the Alcatraz occupation. “Our People have been living like this all the time under the same conditions only now in front of the whole world,” wrote La Nada War Jack in the Alcatraz Proposal.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Eagle Plaza, the entrance of the cell house building, features a Bald Eagle above a shield, which occupiers repainted with the word “Free.” “A tiny island is a symbol of our once great land,” War Jack wrote. “What this island stands for, will grow as a seed through our great country and again, be free as our tiny island is now.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Inside the cell house’s administration office, a parks conservancy employee offers information to guests from behind a plastic shield. Occupiers painted a red hand high on the office’s wall, a symbol of the “Red Power” movement. Many Native Americans participated broadly in social justice movements of the civil rights era. Through the Red Power movement, they fought social oppression of their tribes, demanding fair policies and social programs to help their communities while preserving their self-determination and sovereignty.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

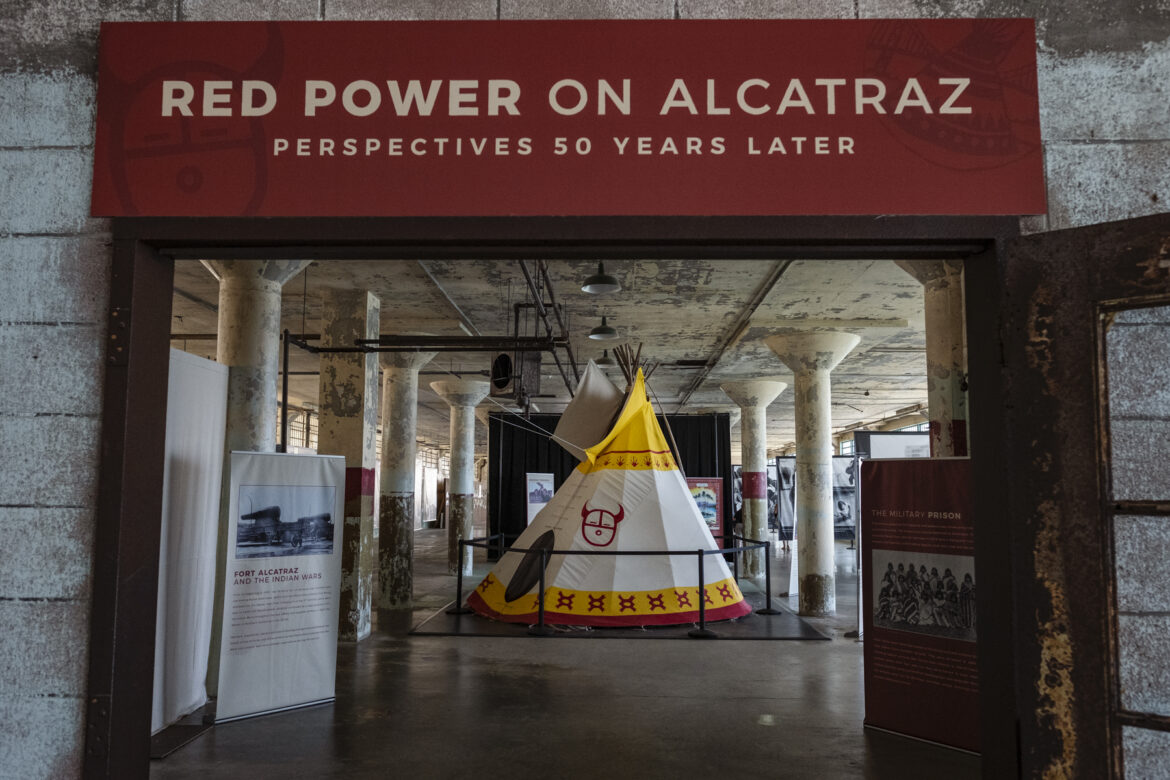

At the far north side of the island, the New Industries Building is home to the occupation exhibition “Red Power on Alcatraz — Perspectives 50 Years Later.” The first installation is a recreation of John Trudell’s teepee, which stood on Eagle Plaza facing the San Francisco skyline during the occupation. The exhibition was curated by the counsel for the Indians of All Tribes in collaboration with the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Alcatraz Island and the Golden Gate Parks Conservancy.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

The exhibit features large canvases from photographers Brooks Townes, Ilka Hartmann and Stephen Shames, original materials and artifacts collected by Kent Blansett, visual storyboards created by Kris Longoria (aka UrbanRezLife) and contributions from the community of occupiers. In the images shown here, Shames captured young families and children who occupied Alcatraz. Families were a common sight on the island, and the activists opened a school for the children.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Visitors view the large canvas posters in the exhibition. “Red Power on Alcatraz” opened Nov. 20, 2019, marking the beginning of the 50th anniversary of the occupation, with plans to run for 19 months, the length of the occupation. Due to COVID-19, Alcatraz was closed most of last year, so part of the exhibition was made available online. Now, it has been extended until the end of 2021.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

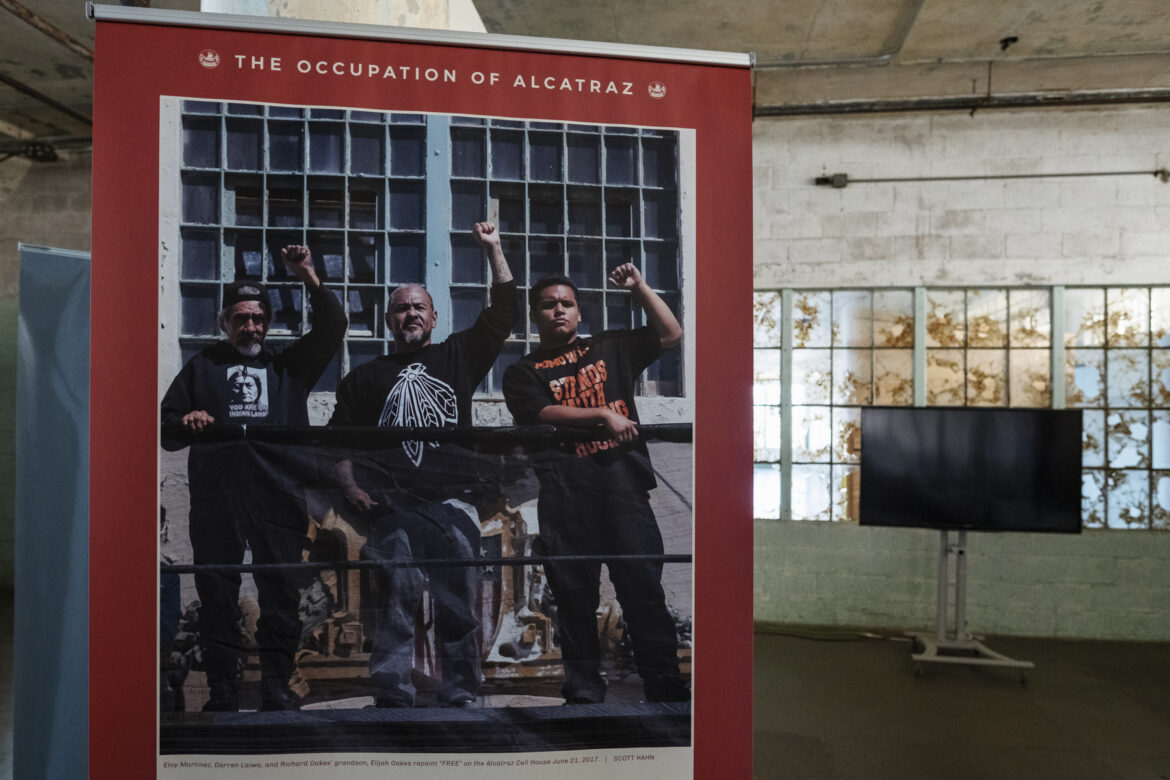

Photographer Scott Hahn took a portrait of former occupiers Eloy Martinez and Darren Laiwa with the grandson of Richard Oakes, who was a leader in the occupation, raising their fists after they repainted the word “FREE” on the shield at Eagle Plaza on June 21, 2017. During the occupation, the Indians of All Tribes wrote a proposal outlining their vision for the island, which included a Native Museum “consisting of Native cultural exhibits. Also there will be a Native Archives and library collection with original documentations of how the “white man” committed genocide to our people and to other peoples in the past and present.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

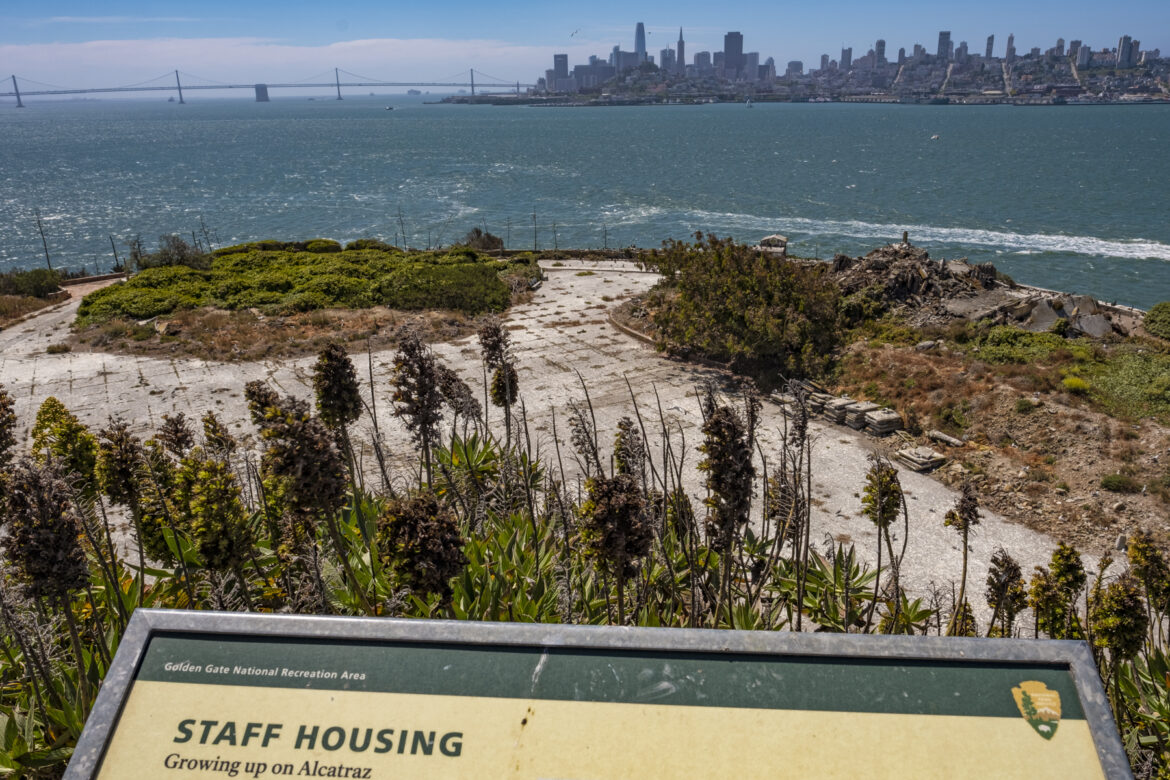

On the parade ground at the top of the agave trail, housing was built in 1934 for the Bureau of Prisons staff and their families. After the penitentiary closed, the apartments were left vacant until members of the Indians of All Tribes and their families moved into them in 1969. During the occupation, several buildings were damaged or destroyed by fire, including the lighthouse keeper’s house, the warden’s house, the recreation hall, the Officers’ Club and the Coast Guard quarters. The causes for these fires are disputed, but the skeletal ruins of some buildings are now an iconic part of the island’s landscape. The U.S. government demolished the staff housing when the occupation ended in 1971.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

The island is also home to a bird sanctuary for species such as western gulls, Brandt’s cormorants, night herons, song sparrows, Anna’s hummingbirds, black Phoebes, Canada geese, pigeon guillemots, snowy egrets and black oystercatchers. A western gull nests on the doorsteps of a former penitentiary residence. Gulls prefer nesting on the ground and fill their nest with vegetation, feathers, rope, plastic and other scavenged items. According to the park rangers’ count, the island is home to about 2,000 western gulls and 800 nests, the second largest bird population on the island. They are outnumbered only by Brandt’s cormorants, with more than 4,000 birds and 2,500 nests.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Western gulls hover below the lighthouse tower. A pair of peregrine falcons guard their two chicks on their nest high in the tower. Falcons often inhabit the island in fall and winter but, in February, they typically migrate south. This year, they nested on Alcatraz. At the time of the occupation, the Indians of All Tribes had a vision for the lighthouse to be used to commemorate Indigenous cultures. In the Alcatraz Proposal, they proposed to, “redress the tower in totem design, telling the story of our people. This is the true statue of liberty representing Freedom for worldwide Peace.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Next to the dining hall, the recreation yard was a point of assembly, and occupiers gathered there for demonstrations. In penitentiary times, prisoners were allowed in the concrete yard, which was secured by high walls and armed guards, to play ball games and exercise on the weekends.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

The cell house is a three-story building with four cell blocks. The D-block held prisoners in solitary confinement. Inmates were assigned individual cells that were 9 feet long, 5 feet wide and 7 feet high. The cell house had a corridor naming system, with hallways names after famous streets and landmarks such as Broadway, Times Square, Sunset Strip and Michigan Avenue. While on Alcatraz, the occupiers “set aside some of the cells for political figures, including the president of the United States, Richard Nixon,” said National Park Ranger Steve Cote. “Also, they set aside a cell for governor of California, Ronald Reagan, the mayor of San Francisco, Joseph Alioto, and the electric company, PG&E.” But they changed their perspective toward Nixon. In 1970, Nixon signed legislation to stop the seizure of reservations.

Yeesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Former prisoner Roy Gardner, a bank robber, described the brutal conditions of living inside the penitentiary in a book titled “Hellcatraz.” The cells were small and offered no privacy. They contained simple amenities such as a sink, toilet, small desk, two shelves and a bed with a pillow and blankets.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

When it operated as a military fortress, Alcatraz held prisoners of war including Native Americans, who were placed in lower-level cells underneath the guardhouse. In November 1894, 19 members of the Hopi Tribe were brought from Arizona and imprisoned for resisting assimilation policies, which forced the separation of their children to enroll in boarding schools and changed their farming practices. The Hopi “hostiles,” as the U.S. Army called the tribe, were held for nearly a year before they were released.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Former occupiers and descendants repainted a political message on a tool shed next to Building 61 reading, “Red Power” with a symbol of a buffalo. For Native Americans in Plains and Plateau tribes, the buffalo’s spirit represents strength, endurance, hope and protection, abundance and manifestation, and is an indication of good times to come. “Alcatraz is a traditionalist Spiritual movement,” wrote LaNada War Jack in the Alcatraz Proposal. “This is our prophecy and the Great Spirit is working for the people. We will win and not just Alcatraz.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

A close-up view to the “Red Power” political graffiti near Building 61. The Red Power movement remained active until 1974, and in addition to Alcatraz sparked six other occupations fighting for Native American rights across the country. These occupations were led by organizations such as the American Indian Movement and the National Indian Youth Council.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Visitors ride the Alcatraz Cruise across San Francisco Bay to return to the city. As the afternoon boat departs, visitors have a final view of the red graffiti marking the occupation. For many visitors, the Red Power on Alcatraz exhibition shined light on the issues affecting Indigenous communities. “It’s shocking actually to just kind of understand some of the atrocities that were permitted to transpire against the Native American people of our nation,” said a visitor from Kansas on the boat. “And to think 47 cents an acre was an acceptable amount for us to give them as far as reparations for that time. It’s overwhelming,” he said.