They are impossible to ignore: encampments dense with people, tents, jerry-built box homes, detritus, building supplies and personal belongings.

Ever since the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing formed in July 2016, it has set its sights on removing encampments and getting their inhabitants off the streets.

At last count, there were 55 camps citywide. By mid-June, the department had cleared 12 and given many of the former residents slots in the city’s three navigation centers, which offer sleeping quarters, social services and, possibly, placement in long-term housing.

Their time at the navigation centers was temporary, however. Initially open-ended, stays at the centers were cut to 30 days last fall. Data show that more than two-thirds of people from the encampments returned to the streets after brief stays at the facilities.

The story of one large camp, known as Box City, reveals the impact this policy has had on residents. Many believed the navigation centers — touted as a model of moving people from “street to home” — would lead to long-term housing. But they were left demoralized and jaded about the government’s ability to help them.

Box City formed in the aftermath of the city’s sweep of Division Street ahead of the 2016 Super Bowl festivities. More than 100 tents were cleared after the city Department of Public Health declared them a hazard. About 20 displaced residents departed together to build Box City at Seventh and Hubbell streets, on the western edge of the Mission Bay neighborhood. At its peak, about 30 people called the camp home.

Last January, the city disbanded Box City — “resolved” is the official term — and placed more than 30 inhabitants in the Mission District navigation center, one of two operating at the time.

‘I’m Tired of This. This Isn’t Me’

For Cheree Munson, the break from the streets was bittersweet. “It was like a vacation, kind of,” she said, holding back tears.

Munson has been living on the streets for two or three years. “I’m tired of this. This isn’t me,” she said. “I used to live in Twin Peaks. I had a car in the garage when I first moved here. I just messed up.”

The center’s no-drugs policy and its overall environment, which was less restrictive than a city-run shelter, helped Munson fulfill her longtime goal of getting off heroin, at least temporarily.

Like others from Box City, Munson was told by staff that her stay would be temporary but that she could remain while she waited for a bed in the shelter system. That bed, too, would be hers only temporarily — 90 days, as soon as she had reached the top of a wait list that exceeded 1,000 names.

But she said her time at the center ended without warning.

While still far down the list, Munson was roused by the center’s staff one morning in February. She was told to gather her possessions and leave immediately. Her destination: a different interim shelter that could hold her over until her wait-list number was called. But when she arrived, she said, the front-desk staffer told her there was no bed for her.

Confused and defeated, Munson returned to the streets. She retrieved her old box house — a simple but sturdy plywood shelter — from Amy Farah Weiss, founder of the nonprofit Saint Francis Homelessness Challenge, who paid to store five homes at Pier 50 when Box City was dismantled. (The rest were destroyed.)

Munson set up her box beneath the junction of U.S. 101 and Interstate 80, a 10-minute walk from the old Box City. She was in familiar company.

On a morning in April, Munson pointed to a row of boxes lining the sidewalk behind her near the intersection of Alameda and Vermont streets, at the foot of Potrero Hill.

Disappointed by Navigation Center

“Yeah, this is most of us,” she said, referring to eight other former Box City residents who entered the center and left when their time was up, returning to former circumstances. “We are all from navigation.”

The people camped near Munson told the Public Press they were disappointed that the navigation center gave them only brief reprieves from homelessness, rather than the housing they initially expected.

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing would not disclose the outcomes for Box City’s residents, citing privacy laws. Randolph Quezada, the department’s spokesman, said that even with names removed from the data, it might be possible to determine the identities of the former residents.

City records from February described 31 people as having originated from Box City, 23 of whom left the navigation center to return to the streets. The rest transferred to the Civic Center Hotel, another navigation center, for more services. Of those who returned to the streets, 12 “left voluntarily.” Nine left after reaching the end of their temporary stays; one left because of “community/staff violence”; and one departure was marked “other.”

Munson said that after leaving the Mission Navigation Center she felt hopeless about her prospects of permanently escaping homelessness.

“It’s harder this time around because the letdown is so much worse,” she said. “We were promised all these things, and they just don’t seem to care.” Munson recalled that when the Homeless Outreach Team came through Box City, staff encouraged residents to enter the navigation center because it might lead to housing.

When asked about how the department works with encampment residents, and whether staff temper the expectation that navigation center stays will lead to long-term housing, Quezada declined to comment on commentary from homeless individuals. “I can’t control what people think,” he said.

A Focus on Building Trust

Sometimes, he said, misinterpretations can occur: “Maybe I tell you one thing and you hear something else. Maybe you hear what you want to hear. I don’t know. But what I do know is that the team is focused on building trust.”

The disappointment of returning to the streets — and the stress caused by daily logistical uncertainties — has tempted Munson to return to drugs, she said.

“We decided getting clean was something we wanted to do, but out here you just want to give up again,” she said, referring to herself and her girlfriend, Elizabeth Kidd, who also went from Box City to the center and back to the streets. “And I’m not going to lie; I’ve messed up a couple times since being back out here.”

In late May, Munson and her friends had to choose again between staying on the streets and another 30-day stay at the navigation center. That’s because the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing had “resolved” the new, smaller encampment. Other encampments are clustered in the vicinity, and Quezada said all would be disbanded, possibly by mid-July. In the meantime, the department has set up hand-washing stations and portable toilets for the occupants, he said.

Spanning half a block in the Mission Bay neighborhood, Box City consisted of more than 20 small wooden houses made from found materials, as well as portable toilets that Weiss provided. It was an unremitting contrast to the pristine University of California-San Francisco medical center campus across the street, and a spectacle to Seventh Street motorists and Caltrain passengers rolling along the tracks beside the camp.

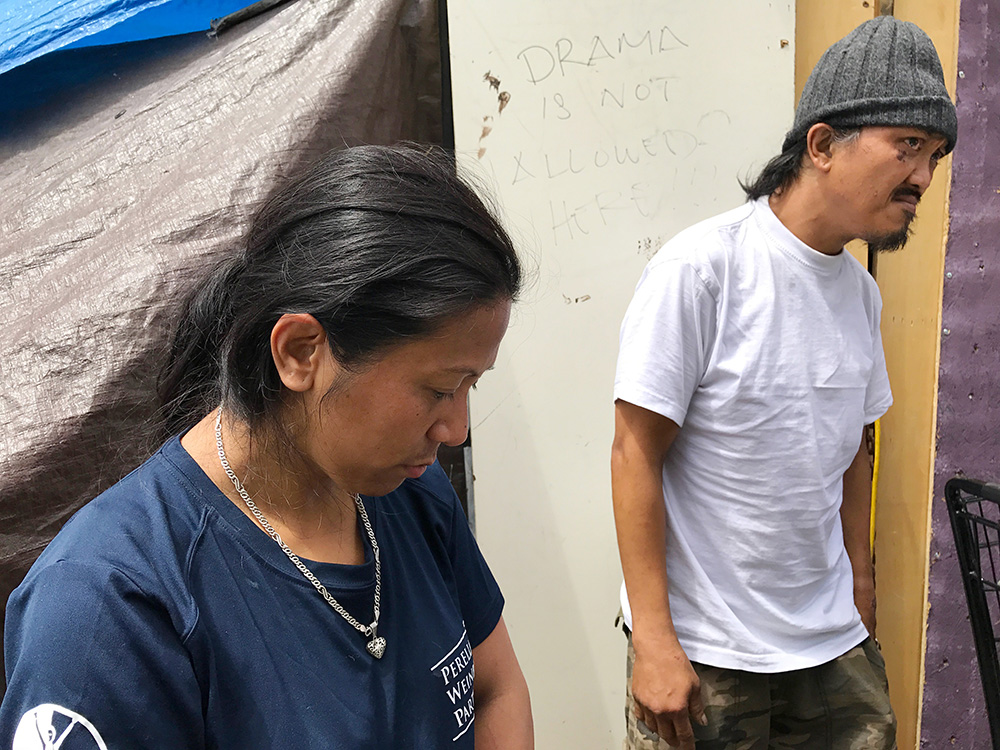

Edwin Marangco, known to friends as “Bad Boy,” was one of the Box City founders. It started with only a few boxes and gradually grew enough to merit an official name, which he wrote on a sign that he posted in front of the homes. Marangco said he hoped it would bestow legitimacy so that “the city wouldn’t call us an encampment no more.”

The name came in handy. “Sometimes we would order a pizza and they would ask where to deliver it, and I would tell them ‘Box City’ and it worked,” Marangco said.

Stability and a Sense of Security

Members were encouraged to build their own box homes, which would withstand the city’s unpredictable weather while being aesthetically pleasing, Weiss said. They prepared meals together and created rules, such as rotating cleaning duties to keep the space in and around their boxes from overflowing with garbage and disturbing outsiders.

Besides stability, Box City gave residents a sense of security. When someone was away, neighbors guarded against theft.

Kidd, who has been living on the streets for about three years, felt that the community provided protection. “People became like your family,” she said. “If you’re out here by yourself, it’s kind of risky.”

“We looked after each other,” said Jonathan Mesa, a former Box City resident, “but it’s hard now that we are all scattered.” He and the others, gathered at Alameda and Vermont streets, did not know where 17 former neighbors were living after departing the navigation center.

Jacob Young, another former resident, said the primary flaw of the navigation center was that it disrupted the relationships that developed at Box City. “We came in and they separated everybody,” he said. “They don’t understand the community aspect of us.”

In September, the Mission Navigation Center stopped allowing people to stay indefinitely — for as long as was necessary to address the factors that kept them on the streets. Instead, the center enacted 30-day limits, though people could stay longer if doing so would bridge the wait times to get into 90-day traditional shelters or obtain other services. In April, the navigation centers began experimenting with 60-day stays to make them more appealing.

Options for Shelter or Treatment

The shift to shorter stays freed up slots that could go to new arrivals from encampments throughout the city. The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing focuses on camps that have at least six tents or box homes, have existed for at least a month and present health, safety or other significant community concerns.

Camp residents are always offered temporary slots in the navigation center, but they may also opt for treatment programs or temporary shelters, Quezada said. People can bring tents, boxes or other possessions with them to the center as long as there is space. They may also bring pets.

“We expect most people to come with us, to move into the navigation center. But, yes, people can say, ‘No thanks, man,’” Quezada said. “We work really hard to make this stuff compelling. And that you’re going to want to do it. But we can’t compel.”

Records show that former residents of encampments who move to the Mission center are not likely to end up in long-term housing in San Francisco.

Instead of being a likely route to long-term housing, the navigation center has become “another type of temporary shelter,” Weiss said. “It makes it appear that there is progress — if someone thinks progress is tents disappearing from outside their homes and workplaces. It’s really just temporary relief.”

Like others, Mesa was discouraged about being homeless again just months after his stay at the navigation center.

“I liked them, I liked it there,” he said. “I just don’t like that I’m back out here.”

“Yeah, me too,” said Marangco, sitting beside him.

Benefit of Navigation Centers

One major benefit of the navigation center — a point emphasized by Mayor Ed Lee at its opening — is that it provides access to social services. Staff members sign people up to receive CalFresh (formerly known as food stamps), cash aid and Medi-Cal, health care for Californians with low incomes. And they get a respite from the stress of the streets.

Roland Limjoco, a former Box City resident, received an Electronic Benefit Transfer card that functions like a debit card, making him eligible for CalFresh. The card provides $194 a month for food, and he may use it after leaving the center. But, Limjoco said, “They told me I have six months on this before I have to apply again. So that will end this July.”

“I don’t even know where to go to renew it. They didn’t even tell us,” he added.

Limjoco has been looking for a job but had difficulty securing a permanent address to list. So when the Encampment Resolution Team came through Box City in January, he hoped this would be his long overdue chance to enter the workforce.

“Some people just want to stay in a box and are happy staying outside,” he said. “But for me, my goal is to get a job and to stand on my own two feet again.”

His last full-time job was at Old Navy in 2005, when he lived in a shelter secured through the general-assistance program. One requirement for the aid was that residents of traditional shelters attend regular meetings, which often conflicted with his long hours. When he chose work over the meetings, he lost his general assistance, a place to stay — and his job.

Landing a Job Impossible

“‘When you have a place to stay, come find me,’” Limjoco recalled his supervisor saying before letting him go. “And it has been a long time since I’ve had a place to stay.”

Without an address, finding a new job has been impossible. So, for money, he collects cans and bottles in a big bag that he wheels to a recycling center.

Would he enter the navigation center again?

“I’d love to,” Limjoco said. “But no, I’m going to stay in my box.” He suspected that another temporary stay at the center would be too short to land a job and save money.

“Navigation helped people with some things, but why not help them until the end, why stop in the middle?” he wondered.

Marangco, however, thought his odds of landing a job were better if he re-entered the center. “We’ve been stuck here looking for good work so we can pay our rent, but you can’t out here,” he said.

Mesa was dejected. “I was expecting too much, I guess. In a way, I knew we would end up back on the streets. Who would really help you out like that and give you a place to stay, right? It’s too good to be true.”

On May 23, at 6:30 a.m., city crews arrived to clear the little village once again. Gathering their belongings, the nomads wheeled their homes a few blocks away.