When we published the first print edition of the San Francisco Public Press in the summer of 2010, San Francisco was a different city.

That issue featured a story about vacant properties on Market Street and plans for a big development that had yet to break ground. The middle stretch of San Francisco’s main drag had been stagnant for years. Speculators bought and sold parcels without making visible improvements. As we look back, it’s hard to believe how quickly things would change.

The new tech boom arrived. Twitter came to town. Uber took to the streets. Salesforce grew and grew. Development frenzy followed. Blighted mid-Market buildings were renovated or replaced. Longtime low-rent businesses and nonprofits started moving out. Construction cranes shot up in SoMa, the Mission and Mission Bay, in Potrero Hill, Dogpatch and Bayview-Hunters Point.

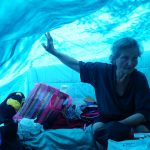

Development generates excitement and energy and jobs — and, sometimes, unintended consequences. Now, backhoes trundle formerly secluded blocks, and homeless people who previously huddled there are forced to move … somewhere.

In more than a dozen community meetings our staff members have attended across the city in the past year, we’ve heard neighbors share stories about proliferating tent encampments and wonder aloud why so many more people are homeless today.

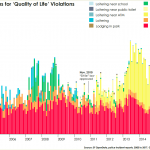

But as we’ve learned from the San Francisco Point-In-Time Homeless Count and Survey in 2017 — conducted one night in January, every other year — the number of people who lack permanent housing hasn’t changed much recently. This year, 7,499 homeless individuals were identified during the count, down slightly from 2015 and up 2 percent from the 2013 count. Overall, the number of homeless adults in San Francisco and the total city population are both up by about 12 percent since 2005. (Counts from 2005 through 2011 did not include a separate tally of homeless youth.)

So, by the numbers, homelessness in San Francisco is not getting worse. Unless you’re one of the men, women and children living on the streets or in insecure housing. For each of them, this is as bad as it gets.

In this issue, we examine the city’s efforts to help homeless people through initiatives in place for years and ones that are expanding under the new Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. Some are experimental, which can be challenging for the people seeking services and for those trying to administer them while working out policy kinks.

Most of San Francisco’s homeless residents were here before they lost their housing. According to a survey conducted with the 2017 Point-in-Time Count, 69 percent of respondents said they were living in the city when they became homeless, and 16 percent were living in nearby counties.

Factors contributing to homelessness are diverse. But the high cost of living here makes it difficult to establish or reestablish a household. That’s something to which a lot of people can relate. As San Francisco’s population and economy boom, low- and middle-income families are moving out. In one of the wealthiest cities in the country, access to affordable housing is an urgent concern for hundreds of thousands of people.

The Public Press is nonpartisan — we don’t endorse candidates or political platforms, and we don’t advocate particular positions. Our goal is to produce investigative reporting and news analyses that give people information they can use to make decisions for themselves, their families and their communities.

Investigating homelessness, a problem often — and erroneously — called “intractable,” takes hard work, compassion toward people who are suffering and an eye on decision-makers, who need to be held accountable for the welfare of our most unlucky and vulnerable neighbors while they strive to improve the quality of life for all San Franciscans.

We hope that you find this report enlightening and thought-provoking. We welcome your comments and questions: [email protected].

Lila LaHood is the publisher of the San Francisco Public Press. Michael Stoll is the executive director and editor.