San Francisco could lose out on hundreds of millions of dollars for rental aid and affordable housing construction with the expected collapse of the Build Back Better social spending and infrastructure bill.

The White House touted the $1.75 trillion spending package as having the “single largest and most comprehensive investment in affordable housing in history,” with $150 billion in housing assistance for low-income tenants. Sen. Joe Manchin, the West Virginia Democrat, derailed the bill by refusing to provide the key 50th vote, prompting some Democrats in early January to press for breaking up the package into separate bills that could end up leaving out housing assistance altogether. Manchin did not respond to a request for comment.

The programs included in the legislation would have allowed San Francisco to offer more subsidies to low-income tenants, repair poor living conditions in public housing and encourage the construction of more affordable housing.

“It just feels like a tremendous missed opportunity to really address a real human need and make major investments in housing as infrastructure,” Michael Lane, state policy director at SPUR, the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association, said of Build Back Better. “We’ve been left adrift now by our federal government.”

Securing federal funding to address the housing crisis, both historically and in recent months, has proved difficult. Lane wanted to see housing affordability addressed in the bipartisan infrastructure bill that Biden signed into law in November 2021, but when funding for housing was cut from that bill, advocates shifted their focus to Build Back Better.

“It’s been so hard for so long to build affordable housing, to support low-income people that on numerous occasions, people, myself included, thought that Build Back Better is a pipe dream fantasy,” said Sam Moss, executive director at Mission Housing Development Corporation, an affordable housing nonprofit in San Francisco. “But we’ve gotten so close now that we’ve proven that it could be a reality.”

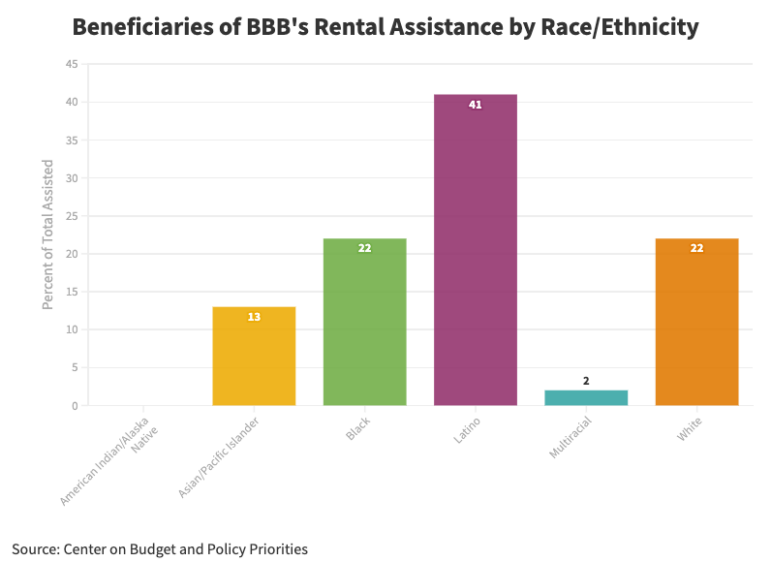

Advocates for low-income residents, nonprofit housing leaders and policy analysts highlighted three main components of the bill that could have increased the availability of affordable housing in San Francisco and significantly improved the lives of low-income tenants, many of whom are people of color: the infusion of funds into direly needed rental assistance programs, tax credits to ramp up construction of affordable housing and funding to address dilapidated conditions in government-subsidized public housing.

Housing as a health strategy

Amie Fishman, executive director of the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California, emphasized the need to redress historically unjust housing policies and alleviate suffering from the coronavirus pandemic.

“The housing investments from the Build Back Better package are absolutely critical for our most vulnerable communities,” Fishman wrote in an email before Manchin announced his opposition to the bill. “Especially here, in the most expensive rental market in the nation, we must honor the foundational role of housing not just in COVID prevention, but also for recovery and rebuilding.”

Advocates cited mold and lead paint in living quarters among their top priorities. They also point to unstable access to housing, a burden that falls disproportionately on Black and indigenous people and other people of color, as a health problem.

“There’s a level of stress when housing is insecure, that is its own health risk,” said Melissa Jones, executive director of the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, a coalition of Bay Area county public health departments. “We don’t spend enough time thinking about housing as a health strategy, because I think if we did, we would think of housing as a human right.”

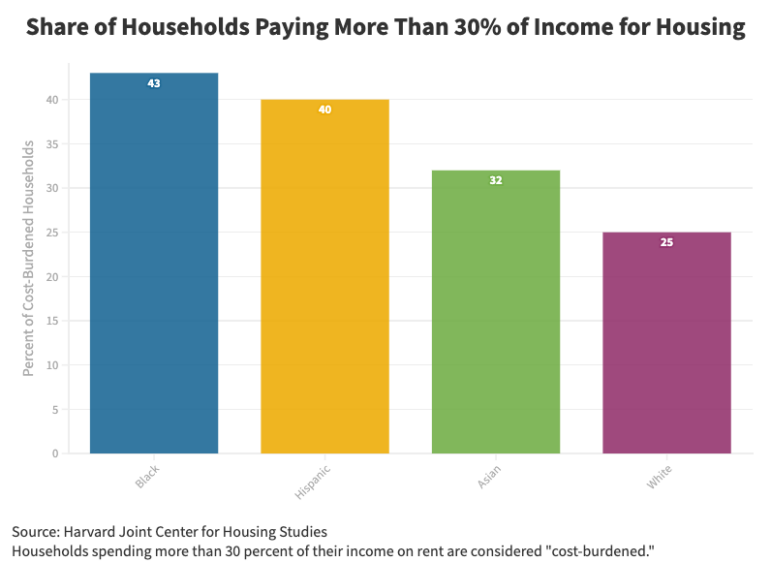

In 2019, 43 percent of Black, 40 percent of Hispanic and 32 percent of Asian households spent more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing, according to a report on the state of the nation’s housing in 2020 from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Just a quarter of white households faced the same cost burden.

The shortage of affordable housing and homeownership leads to a lack of family stability and educational attainment, especially in the midst of the pandemic, said Maureen Sedonaen, chief executive officer at Habitat for Humanity Greater San Francisco.

“It’s such a cascading negative impact if we don’t prioritize this,” said Sedonaen, who previously called the bill “very historic.”

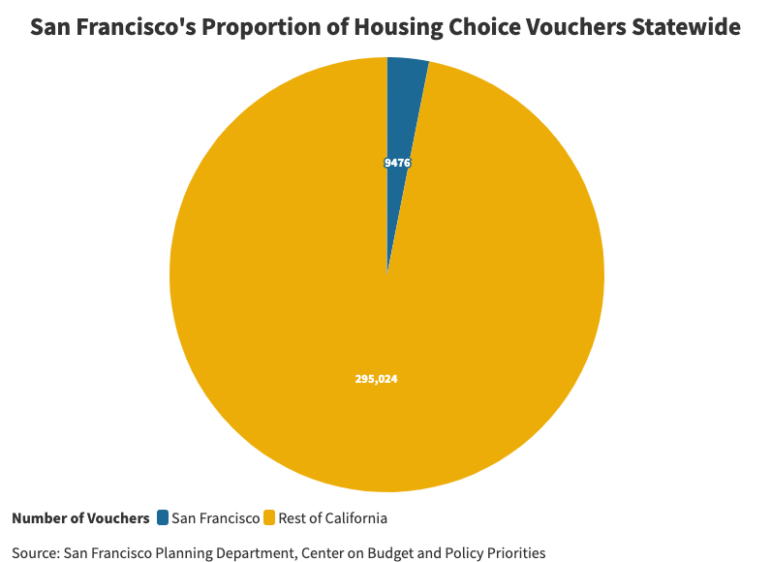

Rental assistance expansion

Key solutions to the housing crisis are federally subsidized rental assistance programs and housing choice vouchers, Moss said. Under these programs, collectively called Section 8, local public housing authorities augment the rent for tenants with very low incomes, those with disabilities and the elderly.

Build Back Better would have invested $26 billion into subsidized rental assistance, and could have assisted as many as 107,200 people in California, estimated the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a policy think tank.

“The subsidy itself is just so valuable,” Moss said. “It’s a direct rent deposit from the federal government every month.” Rent subsidies could be used to pay off the city’s financial stake in new projects much faster, allowing it to reinvest those funds into new construction, Moss said.

Housing assistance today is “vastly underfunded” and three out of four very-low-income households are unable to obtain subsidies, the Harvard report found. Jones noted that waitlists for Section 8 vouchers are years long.

The San Francisco Housing Authority is in charge of managing federal rental assistance locally.

“The Authority continues to closely monitor Build Back Better with excitement and hope that San Francisco will be a recipient of the needed resources,” Zachary Keenan, a legal clerk at the Housing Authority, wrote in a December email. Linda Mason, general counsel for the Housing Authority, did not respond to questions regarding how additional federal funds might be used and equitably distributed.

More tax credits

The Build Back Better legislation would have also expanded the availability of tax-exempt bonds to subsidize the construction of affordable rentals.

Lane of SPUR described the bill as “perfectly aligned” with California’s policies on financing new affordable developments.

Increasing the amount and value of low-income housing tax credits would allow them to “be leveraged with those billions of dollars at the state and local level to really ramp up production in a tremendous way,” he said.

Without federal aid, California can still try to tackle homelessness and affordable housing on its own, though Lane said these efforts will likely be less effective.

“We need more resources and not to have the federal government as a key partner really undermines our efforts and will increase human suffering as a result,” he said.

Another Build Back Better policy change would have allowed bond funding to extend across more projects, creating or preserving more than 170,000 affordable homes in California over 10 years, according to a letter from Gov. Gavin Newsom to Congressional leaders.

“Provisions in the BBB plan will double the amount of bond authority available to California projects,” Audrey Abadilla, a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, wrote in an email before the bill stalled.

Pushback regarding public housing

Build Back Better also included $65 billion to repair, renovate and in some cases replace the nation’s existing public housing stock to address the system’s decades-old maintenance backlog. Estimates for the funding shortfall were as high as $70 billion in 2019, the National Low Income Housing Coalition calculated.

However, not everyone agreed that Build Back Better would bring improvement.

Public housing tenants and anti-displacement activists protested outside House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s San Francisco office in December against the replacement of some public housing units with affordable units in mixed-income developments — a process that could have been accelerated with increased funding from the federal spending package. They want to see more money funneled into the preservation of public housing.

Though it is not clear if the federal government will allocate any funding for public or affordable housing in the coming months, what is clear is that advocates are not giving up hope.

“We really want to continue to insist that there’s an important role for the federal government to play and whatever that looks like — whether it’s a series of bills or there’s a housing package that we can come together around,” said Lane.

“The need is so urgent right now and many people are in desperate straits,” he added. “We’re not going to give up.”