Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.

San Francisco may be missing out on a solution to its affordable housing crisis that other cities are now using to add hundreds of new units each year: backyard cottages.

With a few small tweaks to zoning and building codes, the city could boost its housing stock by as much as one-third and offer additional homes and create more affordable options.

Adding tiny, freestanding structures behind single-family homes across the city would increase density while preserving neighborhood character, proponents say. This would go a long way toward satisfying the city’s official policy of “infill development,” putting more housing on existing underutilized land. But first, the city would have to tweak existing building regulations tailored to mid-20th century lifestyles.

The trend is catching on, with small apartments popping up in urban backyards across North America. Like attached “granny flats” within existing buildings, backyard cottages are smaller dwellings, tucked away off the street — typically 200 to 800 square feet — with little aesthetic impact.

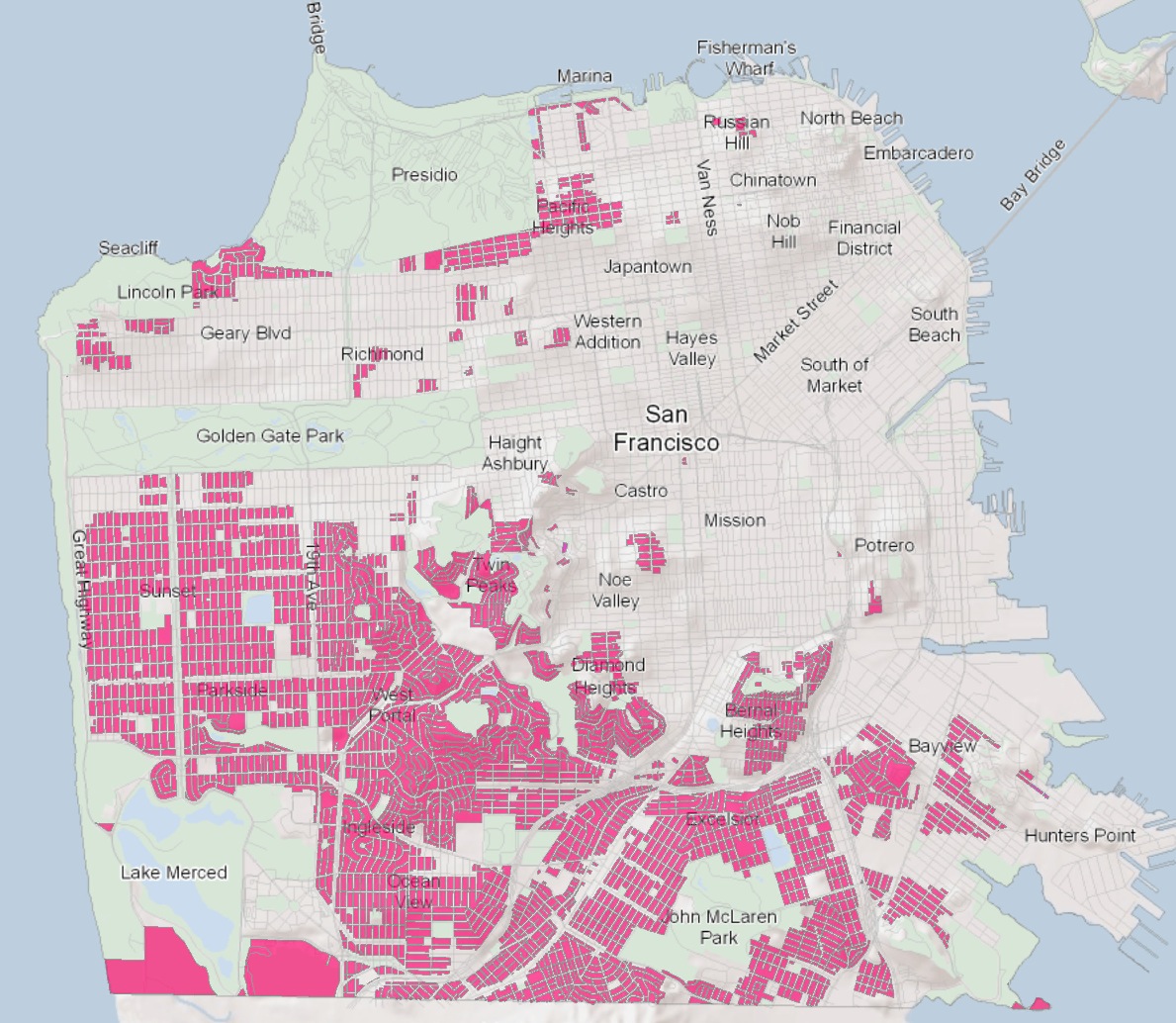

But remarkably, San Francisco seems stuck in a 1950s zoning mentality, mandating single-family dwellings with large backyards across nearly two-thirds of the city’s residential land. Backyard cottages are nearly impossible to construct within city limits, due to a combination of zoning laws, labyrinthine building codes and a lugubrious review process that grinds development to a halt when just about anyone protests.

By legalizing backyard cottages, the city could theoretically add another residence to each of its 124,000 single-family lots, increasing the overall number of San Francisco households by 33 percent.

Zoning for single-family homes in San Francisco. Image courtesy of Dan Sider, San Francisco Planning Department.

Some economists argue that flooding the market with that number of new homes could have a big effect on housing affordability in the long term. Backyard cottages, constructed one at a time by homeowners, would presumably reflect a wide range in prices and offer more affordable options for renters. They would also make possible new, flexible living arrangements for family members and friends.

West Coast and Beyond

In more than a dozen cities across the country that have recently legalized backyard cottages, homeowners proved eager to build them.

Seattle has been progressively legalizing backyard cottages since 2006. Today, there are 155 legal cottages citywide, and the rate of construction is increasing. As of last month, 63 permits had been issued for 2014. With two-thirds of the city’s land zoned for single-family homes, there is potential for many more.

In Portland, Oregon, backyard cottages have been legal since 1997. But they took off after 2010, when the city waived the $8,000 to $11,000 charge for building each new unit. Since then, the number of “secondary suite” permits has tripled. Though Portland’s permitting records do not make a distinction between backyard cottages and other kinds of secondary suites, Eric Engstrom, principal planner for Portland, estimates that about half of the city’s 728 secondary suites are cottages. The city recently extended its fee waiver until July 2016.

Then there is North America’s backyard cottage capital: Vancouver. There, backyard cottages are called “laneway houses” and have been legal on 90 percent of single-family lots since 2009. In just five years, the city has issued more than 1,000 laneway house permits.

Good for Homeowners, Tenants

Advocates say backyard cottages benefit both owners and their tenants, who often already know one another.

“Intergenerational living is driving a lot of this stuff,” said Sam Hagerman, owner of the Pacific Northwest-based builder Hammer & Hand. Hagerman, who started building cottages about eight years ago, estimates that half his clientele build backyard cottages for family members, such as grown children or elderly parents.

The trend is also taking off in California, especially in smaller Bay Area cities.

Kevin Casey, founder and CEO of East Bay builder New Avenue Homes, estimated that 80 percent of his clients built cottages for family or friends. Since homeowners are more likely to charge them below-market prices, if anything, cottages offer affordable housing that requires no government subsidies.

For other renters, cottages are often more expensive than normal apartments of the same size or in-house granny flats, but almost always cheaper than single-family homes, said Alan Durning, founder of Seattle’s Sightline Institute and author of “Unlocking Home: Three Keys to Affordable Communities.” They also allow renters to live in neighborhoods they might otherwise never be able to afford, he said.

Casey estimates that monthly rents for backyard cottages in the Bay Area range from $1,900 for a small one-bedroom home, to $2,500 for a larger one-bedroom, to $4,500 for a big two-bedroom with an office. That rental income can provide a homeowner with help paying off a mortgage.

Backyard cottages could also open up many homes owned by the aging population of baby boomers. In San Francisco, 73 percent of homeowners are over 45, according to 2012 U.S. census estimates; meanwhile, the AARP estimates that 85 percent of Americans age 50 or older want to age in place. By moving into a cottage in the backyard, these homeowners would be able to stay put, while creating more housing options for young families.

Legal Stumbling Blocks

In San Francisco, however, it is nearly impossible to build a backyard cottage.

Under the city’s zoning laws, only a tiny number of lots can legally add backyard cottages. According to a 2013 study by the Asian Law Caucus, zoning restrictions provide for only 55 secondary suites across the city.

The restrictions date back to a 1978 rezoning of all residential districts. Even after California adopted the 1982 Mello Act, which promoted the building of secondary suites as a source of affordable housing, measures to allow their construction in San Francisco were not supported by the mayor and failed before the Board of Supervisors.

Throughout the 1990s, some supervisors attempted to expand the number of legal secondary suites, but these efforts died in the face of strong neighborhood opposition to increased density.

Even if zoning laws allowed backyard cottages on more lots, the building code’s requirement that the back 25 percent of a single-family lot be left open for a yard would make them extremely difficult to build. A standard single-family lot is 2,500 square feet in San Francisco, so a homeowner would have to squeeze both a home and a cottage into the buildable 1,875 square feet.

What’s more, a cottage that is up to the building code might not even get through San Francisco’s discretionary review process, which allows almost anyone to protest any building permit, even if it complies with the code.

While unusual among cities, this review process takes into account San Francisco’s sardine-style housing layout, since what one resident does often has some effect on his or her neighbors, say supporters of the current system.

“The land review and approval process is very detailed, very democratic and very San Franciscan,” said Dan Sider, senior advisor for special projects at the San Francisco Planning Department.

Others say this process is overkill. “It’s absolutely brutal,” said Rodrigo Santos, a structural engineer with more than 25 years of experience building in San Francisco. He said discretionary reviews can slow a project down by up to 18 months and cost the applicant hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not shut the project down completely. “There is a saying here: In San Francisco, you don’t own your house, your neighbor does.”

City’s Changing Character

Existing zoning laws are old, and times have changed. Backyard cottages may offer neighborhoods a way to adapt to those changes.

Jake Wegmann, a Ph.D. student at U.C. Berkeley’s department of Urban Planning, has extensively researched secondary suites. He said zoning laws for most major Californian cities date back to the 1950s, an era when the nuclear family predominated. Census data from 1960 shows that in San Francisco, families with at least one child under 18 accounted for 44 percent of households. Planners zoned accordingly, mapping large single-family districts, with fewer options for individuals.

In 2010, however, families accounted for just 16 percent of households, while nearly 40 percent of residents lived alone.

Kol Peterson, an advocate for secondary suites who runs the website accessorydwellings.org, called this a “mismatched housing supply,” in which a majority of the population wants to live in a minority of the housing stock.

That is certainly true for San Francisco, where one-third of the city’s housing units are single-family homes despite the dwindling proportion of families. Even at a time when demand for rental units far outpaces available supply, single-family-zoned neighborhoods remain dominated by homeowners, with only 14.5 percent of homes rented out, according to the city’s 2007 Housing Element Report. Backyard cottages could open up these neighborhoods for renters.

But the influx of renters is exactly what many homeowners in these neighborhoods fear. Wegmann said that while detractors frequently cite increased density and tough street parking as their biggest concerns, their greatest fear is that the character of the neighborhood itself might change.

“There’s a quote passed around among planners in the Northwest, often repeated with a smirk,” Alan Durning wrote recently for the Sightline Institute. “It’s an exaggeration, but it’s not a lie: ‘In India, they have the caste system. In England, they have the class system. Here, we have zoning.’”

Changes Afoot

Legalizing backyard cottages themselves may not be on the current political agenda, but current reforms are attacking some of the impediments to expanding the number of units on a property.

In April, the Board of Supervisors approved legislation to allow homeowners to legalize existing secondary suites, so long as they are up to code.

Some estimates put the number of illegal in-law units in San Francisco at 30,000 to 50,000.

The board also passed an ordinance allowing the creation of new secondary suites in the Castro — though they will have to be within existing buildings. Many cities that have allowed this type of construction legalized cottages soon thereafter.

Though the urban backyard cottage may seem exotic, a global perspective shows it to be anything but. “Things like secondary units exist all over the world,” Wegmann said. “It’s pretty common for people to just tack on an extra space for a friend or relative. Somehow the U.S. has lost that tradition.”

Part of a special report on solutions for housing affordability in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the summer 2014 print edition.