Many San Franciscans who don’t have permanent homes struggled to stay dry and access inclement weather resources in January amid historic storms that killed at least 19 people statewide and brought heavy rain and winds gusting up to 90 miles per hour across the Bay Area.

San Francisco took steps to get ahead of the crisis: A spokesperson from the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing said the agency increased street outreach and the number of shelter beds available in anticipation of the storms. But as of a week ago, some people said they were having a hard time accessing shelter beds and other resources to protect them from the rain.

We talked with more than two dozen people about the challenges of finding shelter in eight San Francisco neighborhoods over three days during the storms at a time when several shelters were close to capacity, according to the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s dashboard. We talked to many people in vulnerable situations who did not have the ability to search online to figure out where shelters were or how to get to them. Also, the city’s shelter dashboard does not explain clearly which shelters have beds available in real time.

For several weeks, intense rain and wind caused power outages, downed trees, and led to flooding and mudslides. From Dec. 26 to Jan. 18, there were 1,711 reports of flooding to San Francisco’s 311 service center, as well as 1,125 reports of damaged or fallen trees, excluding trees that were vandalized. An additional 1,355 reports were generated about tents or vehicle dwellings, and were coded as “Encampment Cleanups” in a Department of Public Works database. About 60% of these reports were duplicates.

“We have set inclement weather protocols,” Denny Machuca-Grebe, a public information officer at the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, wrote in an email. “Once we see a forecast of less than ideal weather conditions, we put the protocols into action.”

“We are increasing wellness checks, looking throughout our shelter system to flex some capacity where available, discuss with our city partners as to whether a pop-up shelter would be needed, and staff up to support these operations,” Machuca-Grebe wrote in a follow-up email. He also noted that the Homeless Outreach Team deployed extra workers encouraging people exposed to the elements to come inside.

But while we were out reporting, we came across one man in the Tenderloin who had been shivering under the rain for at least an hour before we called the Street Crisis Response Team, which sent representatives to check his vital signs and take him to a shelter. During an early-morning break between storms, we also saw city workers clearing an encampment in the Mission where residents were offered shelter. Those who declined the offer were asked to pack up and move all their possessions — many moved around the corner or across the street — so the Department of Public Works could clean the sidewalk before the next day’s rain.

The department “sheltered an additional 100+ people every night throughout the storm activation,” Machuca-Grebe wrote. He said that extra beds are available during storms on a walk-in, first-come first-served basis for one-night stays Monday through Thursday, and for three-night stays for those who arrive on Fridays.

The Department of Emergency Management also reported that the city’s Healthy Streets Operation Center, a group focused on coordinating efforts among city agencies to address homelessness and street health, had engaged with 160 people living outside in various neighborhoods between Dec. 29 and Jan. 14. Less than half of those people accepted offers of shelter. The department also said that staff from several city agencies transported a total of 410 people to winter shelters.

SEEKING FOOD AND SHELTER

Friday, Jan. 13

10:58 a.m. Inside St. Anthony Foundation, a social services hub for low-income San Franciscans, dozens of people are eating hot meals and warming up in the dining room. Outside, a 58-year-old man named Tim says that he doesn’t know where he will sleep tonight. His belongings are gathered in a duffel bag and a suitcase, which later will fall open as he boards the No. 7 Muni bus heading toward the Haight and Outer Sunset neighborhoods.

When asked what the city could be doing to better support people like him, Tim answers quickly: “We’re not getting housing over here. Been waiting a long time.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

11:30 a.m. Down the block at St. Boniface Catholic Church, nonprofit employees help people identify their belongings with numbered tags so they can retrieve them later from the canopy outside. The church welcomes those seeking a place to rest every day until 3 p.m., giving them a break from the elements and a place to wait their turn to take a shower or do their laundry at St. Anthony’s across the street. Two police officers stand inside the doorway, serving as security.

“There are a lot more people because it’s raining. People are trying to get out of the rain,” says a St. Anthony Foundation employee standing outside the church.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

11:45 a.m. Back at St. Anthony’s dining room, many older people are coming and going –– some of them appear to be residents of the senior housing on the buildings’ upper floors. People continue to leave their property at the entrance. They leave bikes and shopping carts covered with umbrellas and sleeping bags, attempting to shield belongings from the rain, but most of their property is already wet.

One man who commuted from his home near San Francisco International Airport for a meal says that 20 years ago he volunteered at Glide Memorial Church helping feed people experiencing homelessness, and laments that “now things are so damn expensive.” He says he isn’t homeless, but relishes the spinach and other food he can pick up from the foundation.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

12:11 p.m. At Hyde and Turk streets, the “urban oasis” park is mostly empty during a light drizzle. Urban Alchemy employees, who manage the oasis, sit under canopies and play music. Department of Public Works employees sit in another area of the park, gazing at their phones.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

12:15 p.m. On the way to our car, we see a man in drenched clothing, shaking uncontrollably under an emergency blanket. We guess that he has been there for at least an hour, as we passed him on our way to St. Anthony’s. It is no longer pouring rain, but when we speak to him, he can only muster a few words, sharing his first name and that he is cold. We go to the car and grab socks, a towel, a sweater and a tent, and return to offer these to the shivering man. But he can’t stop shaking from the cold, and we think he needs a more serious intervention.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

12:37 p.m. We have trouble finding the right phone number. When we call a number that we find on the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing website, we reach an answering machine. Next, we call 311 and are transferred to the non-emergency police line, where we finally reach a dispatcher. She asks a series of questions about the man’s physical appearance and his demeanor. Does he seem violent? Does he have a weapon? We answer “no” to both. We tell her that he is cold and wet.

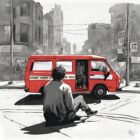

1:04 p.m. The Street Crisis Response Team arrives in a red van with three passengers. Two paramedics prepare to take the man’s vital signs. “I can shake him and have him get up, but he’ll be pissed,” one of them says after asking the man several questions: Does he know what city he’s in? San Francisco. When did he last use drugs? Three hours ago — fentanyl. Does he want to go to shelter, or stay where he is? Shelter. One of the paramedics calls SoMa Rise, a program that connects people with substance use issues to services — such as medical care and housing — to find out if they had room for the night. Now the man is standing, and his breath turns to steam as it leaves his mouth. The paramedics bring him a gray women’s jacket that is slightly too small, two large blankets and a dry pair of pants for him to change into in the van.

Eventually, the paramedics pack up the dry clothes and blankets they brought in a plastic bag, help the man into the back of their van and take off.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

3:36 p.m. We drive to the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood to visit the Vehicle Triage Center, a city-run parking lot where people living in recreational vehicles can park and access showers, bathrooms and social workers who offer case management. At the entrance, we meet James, a new RV resident. James says he’s turning 65 in a week. After the Hunters Point Expressway flooded, James and other vehicle residents who had parked near there were welcomed to move into the lot, he says. James moved into his RV after losing his job in 2020 during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic. He describes his new living quarters as “better than nothing” and “better than getting towed.” He says he believes the program staff are “doing the best they can,” while also providing breakfast and dinner. Propane tanks and generators for heating and cooking are not allowed at the triage center, and so the city stores them for RV owners at the back of the lot. James hopes the program will connect him to permanent housing. “I am just waiting for them to call if they are going to give me a house,” he says.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

4:29 p.m. A van is in two feet of water at Hunters View Expressway next to Candlestick Point State Recreation Area. Vehicle residents lived along this roadway for years before it was flooded during the recent atmospheric river storms. Sewage has leaked into the San Francisco Bay after storm drains overflowed here and around the Bay Area.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

4:35 p.m. The Vehicle Triage Center is surrounded by water, with the bay on one side and flooded streets in other directions. It is windy here and feels a lot colder than other parts of the city. On a stretch of gravel, we meet Rafaela, a resident of the Candlestick RV Park, a private park next to the city’s Vehicle Triage Center. Rafaela is 30 years old and works at San Francisco International Airport. On rainy days, she finds it challenging, even scary, to drive to work. “I drive at 25 or 30,” miles per hour, she says. On the worst days, she has not been able to drive to work. During this dry spell, Rafaela is out walking her dog, Coco, and doing her best to avoid the flooded park.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

4:57 p.m. At the United Council of Human Services — aka Mother Brown’s — a dining room, shelter and city-sanctioned campsite at Jennings Street and Van Dyke Avenue in the Bayview, people are queuing up for tonight’s 5 p.m. meal: bread, fish and rice.

“We are definitely hitting capacity,” said Quincy Carr, a Mother Brown’s employee who used to stay at the shelter himself. St. Anthony Foundation and sometimes even nearby hospitals will drop people off at this shelter, which has a capacity of about 50, to stay for the night. Though people do sleep there, it does not have beds, only tables and chairs. Sometimes people sleep in a portable toilet outside the building. People can bring in service animals or personal items, but no mattresses or bedding are allowed to avoid a bed bug infestation, Carr says.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

5:46 p.m. We meet Javon while he is standing in line for a meal. He came to San Francisco after Hurricane Katrina decimated his home town of New Orleans in 2005. Mother Brown’s Dining Room is a resource hub to him and people in the neighborhood, but Javon thinks “it needs to be fixed up and remodeled.” He says he has had trouble finding a job while living outside and says that it’s hard to keep himself clean and presentable for the workday. He lived at the sanctioned tent encampment next to Mother Brown’s building, where tents are raised on platforms a few inches off the ground, but the street still floods. He says he is grateful for shelter, but the rules are strict. “We gotta follow rules, but they start being abusive,” Javon said. “It’s mental abuse.”

Javon says being a black man experiencing homelessness presents bigger challenges. “We are the only race that has to keep starting over,” he says, adding his feelings about local government and elected officials in San Francisco: “They don’t value life. There’s no equality. Some people can just eat and go to school, but I can’t.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

8:58 p.m. We arrive at St. Mary’s Cathedral just before the shelter there stops its official intake for the evening. The church functions as an emergency shelter at night during San Francisco’s rainy season as part of the Interfaith Winter Shelter program. The church infamously made headlines in 2015 for periodically using automatic sprinklers to spray people who slept on its steps.

But the entrance to the shelter is hard to find. We walk all the way around the church and try two locked gated doors before someone inside spots us. The site supervisor, Regina, estimates that about 60 people will spend the night and leave by 7:30 a.m. Two weeks ago during a storm, there was a blackout at the site, but she says the shelter was able to get its hands on lamps, a generator and other supplies to stay open. Regina says that a family stopped by earlier today and told her they were having a hard time finding a shelter, but they were unable to stay at St. Mary’s as the cathedral shelter does not allow children.

In his email responding to our questions about shelter availability, Machuca-Grebe wrote: “For families with children and young adults, they can visit one of the Access Points in the community to request placement into an emergency shelter. Families may also access shelter at Buena Vista Horace Mann by calling or walking up to the program. Additionally, pregnant persons may access family congregate shelter through calling Hamilton Family Emergency Shelter.”

![A yellow poster with a red border and black text is stuck to a door with blue masking tape. The poster reads: "Shelter candidates: Please wait on corner of Cleary Street [opposite side of parking lot] from 4:30 to 6:00 pm for shelter staff to admit you

Thank you" in all caps. Behind the glass door inside, a short descending staircase is illuminated by overhead lights.](https://www.sfpublicpress.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SF_Storms_12-771x514.jpg)

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

WEATHERING THE STORM

Saturday, Jan. 14

9:54 a.m. More than a dozen people wait just outside the doors on all sides of the Main Library near Civic Center before it opens at 10 a.m. Near one entrance, we meet a woman who has lived outside without a tent for over a year. She says she went to a shelter last night for the first time as she had no bedding and felt sick with a cold. “It’s hard for women to get in’’ a shelter, she says. “There are more beds available for men.” She says she prefers to keep to herself, but her personal items were stolen a week ago, including a bag with her social security card and birth certificate. She tells us that she filed a police report at the Tenderloin station but didn’t receive any response.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

10:24 a.m. Once the doors open, the woman and others rush in. Inside the library where it is warm, people who spent the previous night outside now surf the internet, sort through their belongings in quiet corners and hunker down at the desks among the bookshelves.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

10:46 a.m. A Street Crisis Response Team and Sheriff’s van pull up outside the library. Later, a Homeless Outreach Team van drives by a man covered in a sleeping bag and emergency blanket sitting in the Muni bus stop. We stop to talk with him. He says his name is Michael and that he is hungry. We offer him some food; he smiles and softly murmurs to us to have a good day.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

12:34 p.m. At 24th and Mission streets, Isolina is smoking cannabis out of a 7-Up can. Several other people take shelter from the drizzle under the eaves of the McDonald’s building. Though Isolina expresses interest in staying in a shelter, she says she does not have a phone or know where the nearest shelters are. We write down the address of the nearest walk-in shelter for her — the Dolores Shelter Program —and call the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s hotline to leave a message telling them where she is standing and that she has expressed interest in going to a shelter. We do this even though the chances are slim that this will lead to her getting help, as the website notes that calls made on behalf of people experiencing homelessness will not be returned.

Damian Pierce, 26, approaches us after seeing us speak with Isolina. Weathering the storms “sucks and it’s f—ing freezing,” he says. “I wake up all wet and it’s miserable.” Though he is 6 feet 7 inches tall, he says he only eats three times a week, and most of his meals consist of fruit that he resorts to stealing. He doesn’t have a phone and for the past week has been sleeping in a tent outside of a building that’s for sale. “I try my best to keep, like, prim and proper and what not,” he says. “I just need a safe, not wet place to sleep.”

Pierce says he has struggled to find long-term aftercare for his alcoholism and has been searching for over a year. He says he was able to get sober during a three-day treatment in Santa Rosa, but he was immediately put back on the street and found it hard to avoid drinking and suicidal thoughts.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

2:07 p.m. We stop at an encampment next to a PG&E facility in the Mission District. Some camp residents are tidying up around their tents and makeshift shelters. On a fence nearby, blue city posters in Spanish and English discourage people from pitching tents near doorways, fire hydrants or public restrooms, and from occupying more than a few feet of the sidewalk. PG&E has also posted signs on its fence, more clearly stating, no camping allowed. A paper notice stapled to an electricity pole announces that there will be an “encampment resolution” at 7 a.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 17.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

3:31 p.m. A dry spell that lasted for a few hours breaks when rain and hail start coming down. In Hayes Valley, while pedestrians seek cover, a woman kneels and washes her head with rain water from the street. She splashes her face a few times before getting up, and searches for food in a green compost bin outside a café. She doesn’t find anything she wants and leaves visibly upset.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

3:46 p.m. A dog stands in the rain near Larch and Franklin streets in the Fillmore District. After a short smoke break, his owner ducks back under their makeshift shelter of plastic tablecloths, cardboard and a set of metal rails typically used for crowd control.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

3:51 p.m. A few blocks away, a man stands under the pouring rain wrapped up in a plastic bag, waiting for the traffic signal to change at Eddy and Franklin streets. His two-person tent and personal belongings are drenched. The slope of Franklin Street carries a stream of water toward the corner where he is camping.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

4:16 p.m. It’s after 4 p.m. and staff at St. Anthony’s Foundation are done serving meals for the day. Across the street, people seek shelter from the rain. They appear to be cold and wet as they carry their belongings in plastic bags and small suitcases. The warming center at St. Boniface and laundry services nearby are also closed for the day.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

4:34 p.m. The rain stops for a few minutes. Behind the Best Buy store in the Mission District, Kevin secures a rainfly cover over his tent to prevent water from leaking inside his sleeping quarters. He uses garbage bags to cover up any openings. The winds have been so strong that “it feels like everything is going to be blown away,” he says. People at this encampment have been using sandbags from nearby businesses to prevent the wind from flipping their tents over. After his last camping site was flooded, Kevin moved to this area. He had lost almost everything in the previous rainstorm, including his bedding. “I was all soaked inside my tent like a wet puppy,” he says.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

5:13 p.m. A man sits outside his tent on a plastic bucket and chats with his partner on Cedar Street in the Lower Nob Hill neighborhood. They share a laugh and the man raises his drink to make a toast. He takes a drink and hands her the bottle. Before it starts raining again, he stretches the top cover on their tent, shaking off the pooled water and throwing another layer of clear plastic over the structure.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

5:21 p.m. As rain continues, people stand outside the Next Door Shelter on Polk Street in the Lower Nob Hill neighborhood, waiting for intake to start. Those seeking a place to stay need to line up early as shelter beds are offered on a first-come, first-served basis.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

5:28 p.m. Across the street from the Next Door Shelter, four people take cover from the rain at a construction site as they wait for the doors to open. A man huddles in a plastic poncho he received from St. Anthony’s Foundation, trying to keep warm. A woman sits on her electric wheelchair, keeping her service dog close.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

5:30 p.m. The rain continues on and off for the rest of the night. A person rests inside a soaked tent on Cedar Street, leaving a grocery cart outside with their finds of the day: a pair of Converse shoes, some clothes and a few plastic bottles to recycle.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

STARTING OVER BEFORE THE RAIN

Tuesday, Jan. 17

A police squad car pulls onto 19th Street from Harrison Street as a group of city employees rounds the corner. One woman wears a black jacket that reads “Homeless Outreach Team,” and three men wear beige vests with “Encampment Resolution Team” emblazoned on the back. At least two police officers and a fire department captain are also part of the group. They are later joined by more police officers, a social worker from the Healthy Streets Operation Center and at least one observer from the City Attorney’s Office. The fire captain is often the first to approach tents.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

“Are you interested in going inside today?” is typically his first question as the group reaches each tent, sometimes preceded by “they are gonna clear all this out today. We have to clean the sidewalk.” Some encampment residents are not near their tents or belongings and their neighbors try to explain where they are, such as one man who is at court. The fire department captain shakes the tents from the outside, sometimes moving makeshift tarps to peer inside and see if anyone is there.

The team approaches a two-person tent where the man inside speaks little English. Bobby, a worker from the Encampment Resolution Team, speaks to him in Spanish. He asks, “do you want to go to a shelter or a navigation center? It’s still raining.” The man chooses neither, indicating that he doesn’t trust city employees. Bobby later meets Armando and helps him put a wrap around his hand after Armando says that he thinks he has a broken wrist and might need a cast.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Though it is dry today, members of the city team say they are trying to clean up the area before the last wave of predicted showers arrives tomorrow. The Homeless Outreach Team has been conducting encampment cleanups throughout the storms with advocates stating in court that the city continued to remove people from the street without providing shelter, violating a Dec. 23, 2022, injunction issued by a federal court as part of an ongoing lawsuit between individuals experiencing homelessness and San Francisco, though officials say the city is complying with the order.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

One encampment resident, Dwayne, says that the mood among members of the Homeless Outreach Team has been more tense since the injunction was issued. In the past, his belongings have been thrown out by the team, he says. Three months ago, a pregnant woman staying in a tent next to him was at a doctor’s appointment when city workers arrived and prepared to throw away her belongings. “They let me grab what I could, like maybe five bags,” he says, “and they threw the rest away. It’s ridiculous.” Starting over without anything is hard, Dwayne says, which is why he is hesitant to go to a navigation center, where he says his belongings were once thrown out when he missed a check.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Although the city is not allowed to force people to move their dwellings, it “may continue to ensure sidewalks are not obstructed and are usable for everyone. And, the City may still ask unhoused people to move temporarily for cleaning activities,” Jen Kwart, director of communications and media relations at the City Attorney’s Office wrote in an email.

During ensuing hours the morning of Jan. 17, camp residents ask what shelter options are available today, but city employees are vague. The Departments of Emergency Management and Homelessness and Supportive Housing did not respond to our questions sent by email asking how many people were offered shelter and the number of shelter spaces available Jan. 17. A representative from the Department of Emergency Management wrote in an email that 10 people accepted shelter offers that day.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Most camp residents choose to stay in the area. They gather their possessions and move across the street or around the block while seven Department of Public Works employees use rakes and shovels to scoop up items left on the sidewalk. A ski, an old television, a garbage can filled with black tubing and a torn foam mattress cover sit among the articles that have been sifted through by residents and are now being tossed into the Department of Public Works dump trucks.

Once the tents have been moved, the streets nearby get a power wash ahead of the last of the atmospheric rivers expected to roll through the next day.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press