Governments have been looking for an effective, cost-efficient way to house their homeless populations, especially the high-need individuals straining public resources while out on the streets. But many are hesitant to commit significant taxpayer money to the long-term interventions that service providers insist are necessary.

Meanwhile, among privately run single-room occupancy facilities outside the master-leasing program, around 1 of every 7 rooms has been vacant, according to the most recent data available from the city Department of Building Inspection.

Meanwhile, among privately run single-room occupancy facilities outside the master-leasing program, around 1 of every 7 rooms has been vacant, according to the most recent data available from the city Department of Building Inspection.

Although they all share a common motivation and goal of helping to house homeless people, each model varies in its specific target population, project components and success measurements. Here’s a comparison:

Santa Clara County

A 2015 analysis of more than 100,000 of Santa Clara County’s homeless individuals between 2007 and 2012 found that 2,800 of the chronically homeless accounted for almost half of public service costs each year — about $83,000 per person.

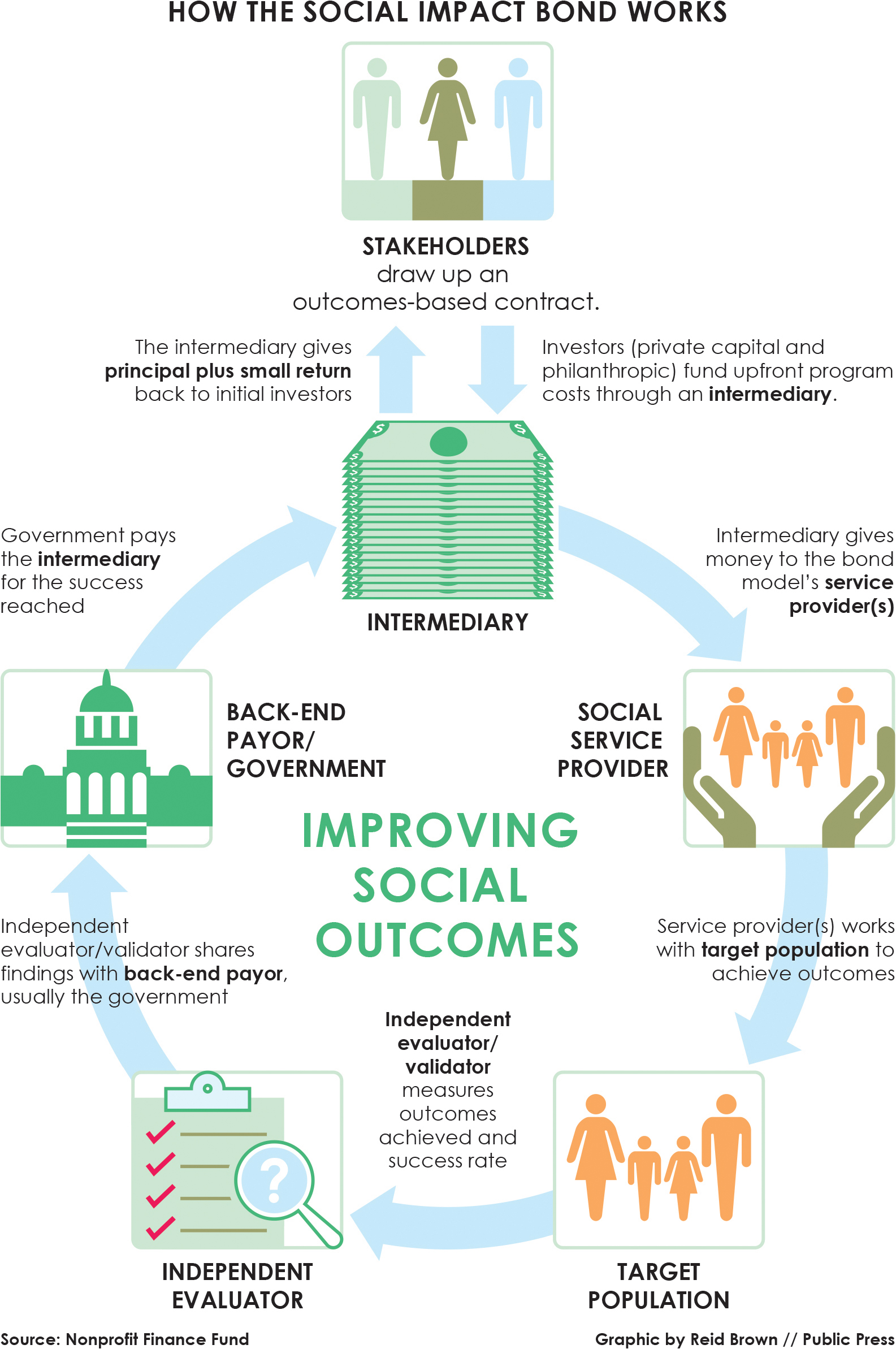

In September 2015, the county implemented a social impact bond, known as Project Welcome Home, that brings in nearly $7 million of private seed money to house 150 to 200 of the highest-need chronically homeless over six years. It also attempts to reduce their interactions with expensive health care and jail services.

Nonprofit service provider Abode Services is responsible for using the money and separate public resources — including $7.7 million in Medicaid services and $4 million in housing units and vouchers — for a “housing-first model” with intensive case management.

Under a previous housing-first program that targeted a broader range of homeless individuals, the county’s costs fell 70 percent annually for those who remained housed through the program.

“The model we’re employing we’ve already done for multiple years,” said Louis Chicoine, executive director of Fremont-based Abode Services. “But we haven’t done it to this intensity. In the last year and a half, we’ve had nine people die as an indication of how acute their conditions are.”

As a result, even though models in Massachusetts and Denver have thresholds for success payments set at one year of housing stability, Project Welcome Home investors start to see their money come back after clients reach just three months.

“In Santa Clara County, they’re working with the sickest people in the emergency room,” said Caroline Whistler, the chief executive officer of Third Sector Capital Partners, a nonprofit that facilitates transitions to social impact bonds. “These people have had no success in housing. If you can keep them housed for three months, that’s enormous.”

Success payments increase on a monthly basis, with a possible return of 2 to 5 percent.

However, Whistler said, because the county wants to see tangible health benefits — even though they are not tied to payments — Project Welcome Home includes penalties if clients excessively use health care services or are incarcerated while on a lease.

Success is “paused” if someone is incarcerated or in psychiatric hospitalization for more than 14 days of a 30-day period, or more than twice, for any length of time, within the period, said Maria Raven, the project’s lead evaluator and an associate professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Raven said success is completely “restarted” if someone is incarcerated or in psychiatric hospitalization for more than 90 days, or in a shelter or on the street for more than seven consecutive days.

The project’s target: having more than 80 percent of participants achieve 12 months of continuous stable tenancy.

As of July, 111 people were housed, with 90 having reached at least three months of stable tenancy and 44 having either hit or surpassed the 12-month mark. There were 59 pauses and 54 resets.

City and County of Denver

Denver’s social impact bond was established in February 2016. Unlike Santa Clara County’s, it ties success payments to one year of housing stability and a decrease — at least 20 percent — in jail-bed days.

A conservative cost estimate puts taxpayer spending at about $29,000 per person on emergency services, including jail days, detox days and emergency hospital visits, said Tyler Jaeckel, an architect of Denver’s bond and a program director with the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab.

“Housing stability is important,” Jaeckel said. “But by measuring jail-bed days, you’re actually demonstrating the impact of the program and can compare that to individuals who didn’t get in the program. Did the program see a reduction in tangible benefit to the government?”

Program participants are people who have been arrested eight or more times in the last three years and came into the criminal justice system without an address or using the address of a shelter.

Of the approximately 2,100 individuals that fit this criteria, Denver’s program, the Housing to Health Initiative, targets 250 over five years with $8.6 million in private investment, $10.8 million in housing vouchers and $5.2 million in Medicaid funding.

Once clients reach the housing stability or jail-bed day reduction threshold, investors start getting repaid with a possible return of 3.5 percent.

In addition to having two measurements for success, the bond model uses two service providers — the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless and the Mental Health Center of Denver — to address the target population through a housing-first model.

“There are complications in having lots of parties, but the benefit if you figure things out is you have more people that already know how to solve this problem,” Jaeckel said.

“Having multiple partners allows for greater systemic change,” he added.

The two providers are dedicating many of their resources to building housing units, another distinctive aspect of Denver’s social impact bond. In other bond models, service providers tend to work with outside developers or leverage existing housing units.

Cathy Alderman, the vice president of communications and public policy for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, said her organization is building 100 units and the Mental Health Center of Denver is building 60 units. Alderman said both service providers work with clients to tailor their housing assignments to the clients’ needs.

“We try to get people into the neighborhoods or areas of town they’re best suited for or connected with,” Alderman said. “Sometimes the first try is not the best fit, so we’ll have to move them to another place in another part of town.”

As of early August, the two providers had housed more than 150 individuals. Alderman said data on housing stability and reductions in jail-bed days were not yet available.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Established in December 2014 as the first U.S. homelessness social impact bond, the Massachusetts model faces a challenge the other three local-level projects do not: creating a statewide impact.

The model uses 18 service providers to do that. It builds on a program previously run by the Massachusetts Housing & Shelter Alliance called Home and Healthy for Good, which provides low-barrier permanent supportive housing to the chronically homeless and has a success rate of 85 percent.

The nonprofit is part of the intermediary group that manages all of the service providers and ensures they are delivering results, said Joe Finn, executive director and president.

“This is very much a leverage model,” he said. “The 18 providers bring in a lot of different resources to the table, and it’s a mixing and matching of subsidies.”

The intermediary group distributes $3.5 million of private money and $7 million of housing vouchers to service providers working to supply 500 housing units for up to 800 people over a six-year period.

The state’s bond model, which is more dependent on public resources than the other homelessness projects, also leverages $11 million in Medicaid service contracts.

“We’re very much aware that ours is a hybrid model,” Finn said. “What made this attractive to the providers is we were able to link all their clients to a Medicaid program that helps support tenants’ (services).”

Success payments are based on whether a client achieves one year of stable housing, and investors can get an annual return of up to 5.33 percent.

Massachusetts is tracking health costs as well. Like Santa Clara County, the state doesn’t tie payments to use of services, but unlike Santa Clara County, it does not pause or restart success metrics.

“Why would we pause anything just because someone needs to be hospitalized?” Finn said. “Even if he makes the decision to leave housing to go into long-term treatment, we consider that a successful outcome. As long as people don’t return to the streets or homelessness of some kind, they’re considered a success.

“We’re truly a low-threshold model,” Finn added. “We’re not fixing anybody. We’re housing them.”

Studies of the program’s first six months found cost savings of $14,365 per client post-housing, excluding administrative costs.

The project’s target goal is for 80 percent of participants to achieve a year of housing stability. The program had housed 524 tenants through July, and more than 200 had been housed for a year or longer.

Cuyahoga County, Ohio

Cuyahoga County’s Partnering for Family Success social impact bond might be the most cutting edge of the four addressing homeless individuals.

Why? It targets people using services from two different systems — homelessness and child welfare — by linking 135 homeless families to their children in foster care and getting them permanent supportive housing.

“But there’s not much to look back to for guidance on intervention models that effectively address both systems’ outcomes and goals,” said David Merriman, who manages Cuyahoga County Job and Family Services and helped create its social impact bond. “Child welfare only focuses on safety and security of a child and family — that’s a higher need than housing. How do we create a service that’s best?”

The program began in January 2015. Nonprofit service provider FrontLine is using the $4 million from investors, as well as public resources such as Medicaid reimbursements and housing vouchers and units over the four-year project to reduce out-of-home placement days, which is the measurement for success payments.

The county, along with the independent evaluator, will weigh the success of the project against other programs in a randomized control trial before deciding how much investors should be repaid.

Merriman said success payments would be made in 2021 only, but there would be no threshold for them as in the other programs.

“We have one of most conservative deals in the country,” Merriman said. “Some deals are more about social impact or the outcome. We understand our investor took on the risk and we’re committed to making payments at whatever level of reduction occurs.”

The project’s goal is a 25 percent reduction in out-of-home placement days. With greater reduction rates, investors could also see a return of 2 to 5 percent.

If all 135 families achieve a 50 percent reduction in out-of-home placement days, the county’s savings, excluding success payments, would amount to $8.5 million.

Merriman said he could not share information on the reduction achieved or how many families had been reunited. But he advocated for innovative structures and partnerships to provide social services.

“Our homeless problem is changing,” he said. “We’re having success with the chronically homeless, but there have been increases in family homelessness. We shouldn’t be waiting for federal funding to come and address these problems.”

Corrections: The initial online version of this article contained two inaccuracies. Joe Finn, executive director and president of the Massachusetts Housing & Shelter Alliance, clarified that Medicaid supports tenant services, not subsidies, and that the state tracks health costs, not outcomes.

This article is part of the special report Solving Homelessness: Ideas for Ending a Crisis, which appears in the Fall 2017 issue of the San Francisco Public Press.