This article is adapted from an episode of our podcast “Civic.” It is the first in a series about the way family courts adjudicate cases that involve a form of domestic abuse known as coercive control, and the advocates and lawmakers who are trying to help victims and their children.

On average in the U.S., more than 1 in 3 women, and 1 in 4 men, will experience physical violence, rape or stalking by an intimate partner, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Nevertheless, when victims turn to family court for protection from their abusers, they often face skeptical judges. And that’s especially true when the abuse doesn’t leave a mark.

That’s what San Francisco Public Press reporter Viji Sundaram found through her reporting on a new movement to protect victims of what experts call coercive control. (See: “Coercive Control: Abuse That Leaves No Marks.”)

“He kept telling her, ‘How can I believe this?’” Sundaram said of one judge’s reaction to a victim’s request for a temporary restraining order to keep her partner away from her. “Just because a woman is staying within an abusive situation, it doesn’t mean she is not abused. And that is what the judge did not seem to understand.”

In San Francisco, the Department on the Status of Women reported in 2019 that crisis hotlines and 911 got more than 15,700 domestic violence-related calls over the previous year.

And it only got worse during the pandemic. Lockdowns limited victims’ ability to safely contact the outside world for help. The isolation increases the opportunity for abuse, aggression and coercion.

A study by the National Commission on COVID-19 and criminal justice shows that domestic violence cases in the U.S. increased by over 8% following lockdown orders in 2020.

That spike also hit San Francisco, according to an organization that assists domestic abuse survivors called Women Organized to Make Abuse Nonexistent, or W.O.M.A.N. Inc. The group reported that in 2020, its San Francisco crisis hotline got 11,000 calls and its Domestic Violence Information Referral Center website had 125,000 hits.

At a San Francisco Board of Supervisors public hearing in May 2020, Beverly Upton, the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium director, described the escalating problem of domestic violence in the early days of the pandemic lockdown in March 2020: “The first couple of weeks, we saw W.O.M.A.N. Inc’s numbers alone go up 130%,” Upton said. “So that was, you know, quite alarming.”

The form of domestic abuse called coercive control can be harder to detect than physical violence. Behaviors like isolating a spouse from friends and family, depriving them of basic needs, spying on them, sexual coercion, intimidation, repeatedly degrading and humiliating them — these are all examples of coercive control.

But the lack of physical evidence often pushes domestic abuse into a gray zone that even survivors sometimes fail to grasp, according to Sundaram.

“In fact, one woman told me when I was going to interview her, ‘You know, I wish he had hit me. Then I would have had a good reason to leave him,’” Sundaram said.

Coercive control is no less ruinous for victims than physical violence, according to Evan Stark, the man who pioneered the concept. A sociologist, forensic social worker and award-winning author of “Coercive Control: The Entrapment of Women in Personal Life,” Stark said his research found that around 25% of abusive relationships involve violence that’s either nonexistent or below the radar — meaning they don’t result in serious injury or hospitalization. But abuse that does exist is equally harmful.

Stark’s work focuses on the cumulative effects of this treatment: “What I call the death by 1,000 cuts — the push and shove, the grab, something that wouldn’t impress a judge, wouldn’t impress a police officer, but whose cumulative weight was such that it could lead to a feeling of being imprisoned.”

Despite such research, according to the domestic violence and sexual assault prevention organization No More, 65% of domestic abuse survivors who come forward report no one helping them when they do. They report that law enforcement treats domestic abuse as a “domestic dispute” rather than an act of escalating violence.

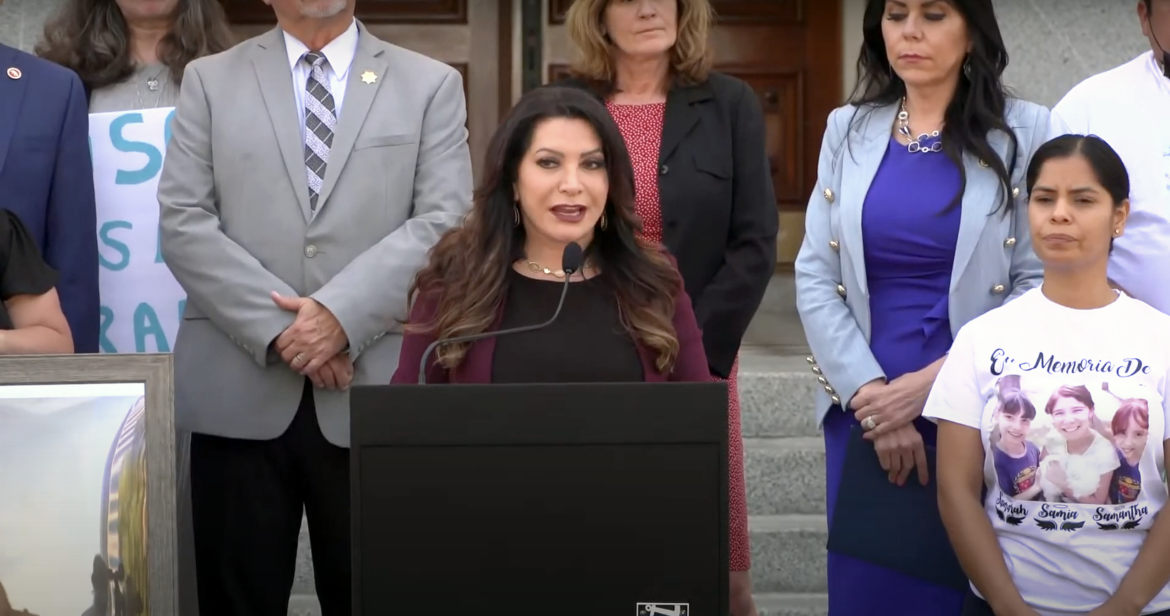

In January 2020, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law that integrated coercive control into the state’s Domestic Violence Prevention Act. Senate Bill 1141 expanded the Family Code to allow the abusive behavior to be used as evidence in family court hearings. It was meant to empower survivors trying to protect themselves and their children during appeals for restraining orders and child custody. But getting family court judges to embrace the new legislation has been slow going.

A 2019 study by Joan Meier, a law professor and director of the National Family Law Violence Center at George Washington University, shows an apparent “systemic gender bias against women” in U.S. family courts. Her study found that women often grapple with the high cost of legal help and are penalized by courts that favor fathers.

One woman using the name Sarah to protect herself from her abusive ex-spouse and father of her two children said she’s been fighting that bias in court for two years.

During her 10-year relationship, Sarah was subjected to threats of violence, absolute control over every aspect of her life, and destruction of property during bursts of rage. Three incidents that involved police even led to the temporary confiscation of his firearms. Their children also endured his volatile need for control. In one incident he physically overpowered their 4-year-old son, pinning him down to a bed by his neck.

Sarah applied for a restraining order in family court. As court transcripts show, the judge said he didn’t believe her testimony.

“The court finds that there are credibility issues that causes the court to doubt as to whether or not abuse as defined by the Domestic Violence Prevention Act has occurred,” the judge said. “The court will deny the request for a domestic violence restraining order.”

The ruling left Sarah dumbfounded.

“Even though, you know, I’ve never damaged property, cell phones, laptops, doors, etc., the judge just found me not credible, which I thought was shocking,” Sarah said. “And it was almost as if he didn’t care. He really didn’t care to look at the facts. He didn’t care to look at the history.”