This article is adapted from a bonus episode of our podcast “Civic.” Click the audio player below to hear the full story.

It has been seven months since Maya Laing and her brother Sebastian, who were 15 and 11 at the time, were violently taken from their grandmother’s Santa Cruz home by court order.

Judge Rebecca Connelly, who oversaw their custody case, rejected the siblings’ claims that their mother abused them, and last October she ordered them into reunification training to repair their fractured relationship with their mother.

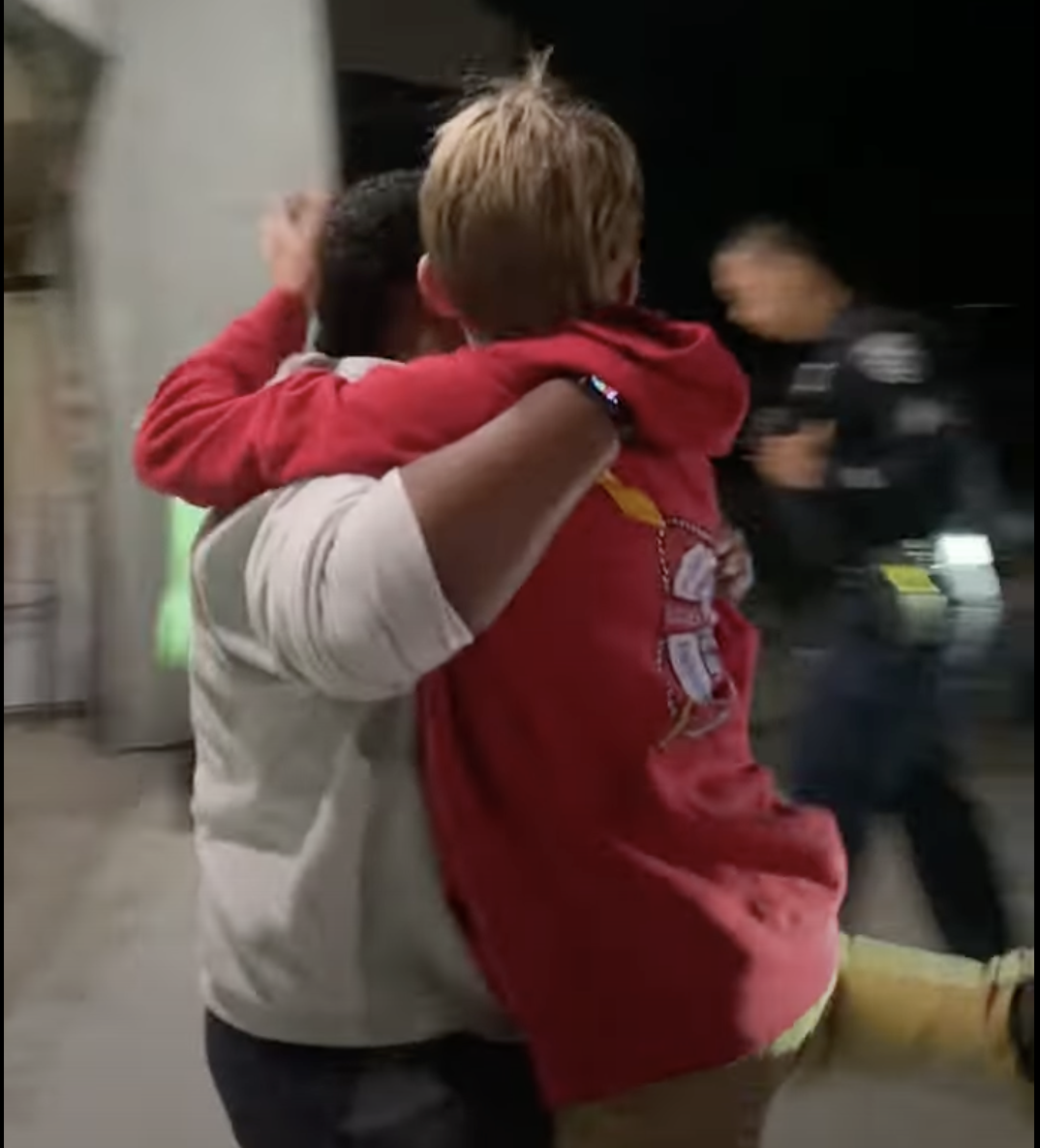

A friend of Maya’s recorded and posted to social media a video of the siblings resisting while transport agents from Assisted Intervention physically overpowered them in October. That was the last time Maya and Sebastian’s father, his family and the children’s friends had any knowledge of their condition — until now.

On May 29, the siblings posted a series of videos to social media announcing that they had “escaped” their mother’s custody and describing what they endured during their transport and their four-day reunification training.

They said they were taken to an Airbnb where their mother awaited them along with reunification trainers Regina Marshall and Lynn Steinberg. They said they were placed in a room where doorknobs had been removed and where a mattress was pushed against the doorway to keep the door shut. They were guarded by the same transport agents who had overpowered them in Santa Cruz. At one point, the siblings said, one of the agents slept in a bed next to the one they shared. When they were caught exchanging whispered words of comfort, they were banned from speaking to each other.

They said that Steinberg told them that she would “break” them.

“They called us liars and psychopath,” Maya said in one video.

“They, like, threatened to send us to a camp, like a wilderness camp, where if we wouldn’t comply, we wouldn’t be given food or blankets,” Sebastian said.

In response to a written request for comment, Maya wrote that she and her brother viewed their transporters as “kidnappers that we were forced to placate.”

Maya also refuted an allegation by Steinberg that her father was involved in gathering the crowd that arrived to witness their removal from their grandmother’s home. “Our dad in no way orchestrated our protest to being taken. We did what was the only reasonable response to three aggressive strangers, backed up by police officers, coming after us and trying to drag us into a strange car in the middle of the night.”

Maya and Sebastian’s mother, Jessica Laing, responded to a request for comment by emailing a link to a National Center for Missing and Exploited Children webpage featuring two missing child posters of Maya and Sebastian.

Steinberg and Assisted Intervention did not respond to a recent request for comment for this article. In response to a request sent in January, Assisted Intervention sent a brief email stating, “Circumstances like this one are complex.”

In the meantime, local supporters who spoke out at public events and on social media in reaction to Maya and Sebastian’s removal have gained ground. One month after Maya and Sebastian were taken, Santa Cruz lawmakers held a press conference outside their grandmother’s home to announce local legislation that would ban transport agents from getting physical with children. And as Viji Sundaram recently reported for the Public Press, Senate Bill 331, also called Piqui’s Law: Keeping Children Safe from Family Violence, was unanimously endorsed by California’s Senate Judiciary Committee last month. If the bill is approved by both houses of the Legislature and signed by the governor, it would establish judicial reporting requirements on reunification training and on expert testimony in child custody proceedings.

Several states are considering similar bills to comply with a provision in the federal Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022. The act promises states up to $25 million in grants if their reforms comply with national requirements.

If you or anyone you know is suffering from domestic abuse, help is available. The National Domestic Violence Hotline provides confidential assistance to anyone affected by domestic violence through a live chat and a free 24-hour hotline at 800-799-7233. The California Partnership to End Domestic Violence offers an online tool for finding local organizations and community resources by region.