California politicians expressed outrage in March when details of a White House budget proposal suggested President Trump would slash a $1 billion environmental grant for restoring San Francisco Bay marshes. And they were apoplectic about the executive order revoking special status for wetlands considered until now to be “waters of the United States.”

But when it comes to weakening environmental protections, sometimes California’s wounds are self-inflicted. For nearly a decade, the real estate and construction industries have pursued a legal strategy that has undermined the landmark 1970 state law that some cities had used to help protect their waterfronts from sea level rise, a Public Press review of thousands of pages of legal and planning documents shows.

After lower courts chipped away at the long-held interpretation of the California Environmental Quality Act, the state Supreme Court in 2015 overturned decades of land-use law by upholding lower court rulings that cities could no longer require developers to take into account the effects of climate change on their projects. The decision has unsettled public officials and planners, and critics say it will allow real estate interests to saddle taxpayers with a gigantic bill to defend against rising seas.

At the same time, the state Legislature, controlled by the Democrats, and Gov. Jerry Brown have neither proposed amending the law nor drafted new statutes to encompass the effects of climate change on coastal development. In January, Brown tasked scientists with reviewing the latest research on sea level rise, and preliminary guidance and preliminary guidance was published in April.

Local and regional governments also have been slow to respond with new regulations or funding measures.

Lawyers who specialize in compliance have circulated memos and held several meetings to share strategies for conforming to this interpretation of CEQA. Although many project plans do address sea level rise, public filings are now peppered with references to the 2015 case to inoculate developers from challenges by planning agencies or environmental groups.

The development industry has a lot at stake. Scores of buildings are queued up for construction on prime waterfront land that scientists say could be intermittently or permanently underwater by the end of this century. These include big projects such as office parks, residential towers, hospitals and entertainment venues in which some of the largest development firms in the country have collectively invested tens of billions of dollars.

Local leaders have touted tax revenues and their own political legacies to advocate large-scale development along the water’s edge — even amid warnings from climate researchers that many low-lying areas will require major public investment to be protected adequately.

The state’s highest court has complicated governmental planning efforts.

The decisive case, California Building Industry Association v. Bay Area Air Quality Management District, did not turn specifically on sea level rise but ultimately limited the reach of the California Environmental Quality Act, known as CEQA. In their opinion, the justices accepted the argument from one of the state’s biggest developer lobbying groups that the act concerned only the “effects of a project on the environment,” and not changes in the environment that could affect a project. Those include risks from sea level rise flooding, wildfires, earthquakes, shifting wind patterns, air quality and carbon emissions that warm the atmosphere.

As a result, industry lawyers argue that under CEQA, waterfront developers no longer appear to be required to pay for expensive fixes to protect their properties from flooding by elevating building entrances, waterproofing ground floors, constructing levees or seawalls or using other engineering techniques.

RELATED: Timeline of Rulings, Actions That Blunted CEQA

The Public Press found that since 2011, developers of at least eight major Bay Area waterfront projects have included key language from court rulings in dozens of land-use filings and lawsuits, some in an effort to block requirements to build or pay for flood protection measures. Six of the projects used this tactic in environmental planning documents filed after the high court’s ruling in December 2015. Among our findings:

- Statewide, developers, cities, environmentalists and others have argued about the scope of CEQA in at least 15 real estate lawsuits since 2009, when courts in Southern California began reviewing challenges to the law.

- Two cities — San Francisco and Menlo Park — have used the Supreme Court’s decision upholding the CEQA reinterpretation to justify their own land-use plans.

- Three companies seeking to build on the San Francisco Bay waterfront have used the industry association case to attack regulations or suits: the Golden State Warriors; Facebook, which expanded its Menlo Park campus; and the Redwood Landfill in Novato. Developers of five other major projects, including the mixed-use development at Pier 70 in San Francisco being built by Forest City, cited the language limiting CEQA in environmental review documents or in court when analyzing sea level rise, air quality, wind or other environmental effects.

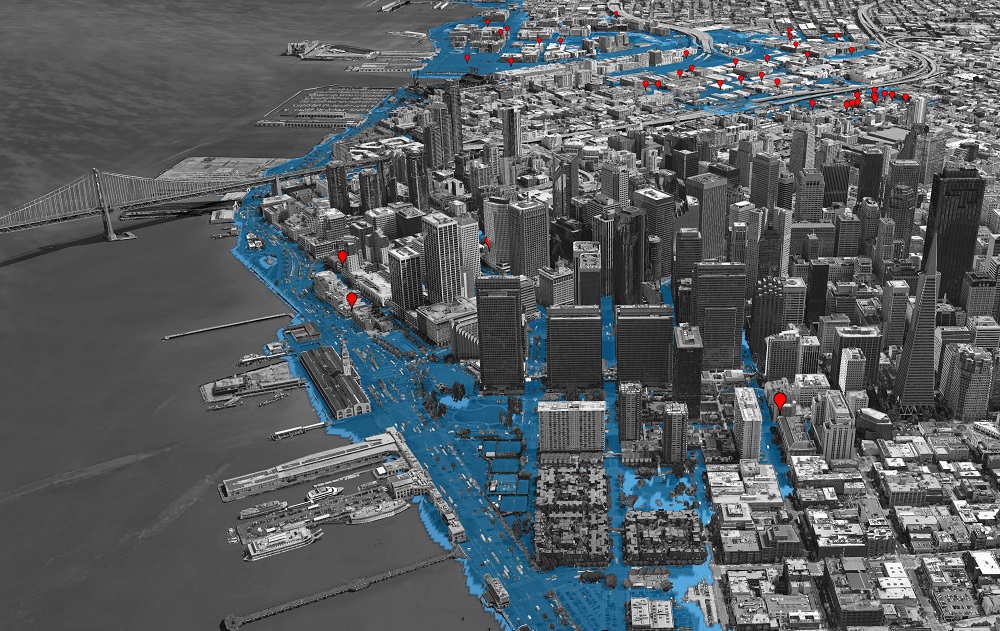

In July 2015, the Public Press reported that scientists projected that sea level rise, combined with the severe storm surge, could push the bay 8 feet above today’s high tide by 2100. Leading agencies, such as the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, concurred with that finding. A citywide task force last year issued a wide-ranging report outlining the dangers to the city’s heavily urbanized eastern waterfront.

Since then, predictions for sea level rise have only worsened. Scientific papers have documented the accelerated melting of ice sheets in Antarctica and glaciers in Canada — both the result of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas pollution from industrial activity. These measurements, combined with new atmospheric models, have pushed the federal upper-limit prediction for occasional flooding above 8 feet along the California coast by 2100, even without a storm. (For more on the science see Local Planners Brace For Antarctic Ice Melt.)

Despite growing alarm, local land-use approvals on the waterfront seem to have speeded up. At least eight large-scale developments situated below 8 feet in elevation are proposed, including a residential tower on Howard Street in San Francisco and a marina in Alameda, the island city that could be more than half flooded by 2100, according to the most pessimistic sea rise scenario. (See Solutions to Bayfront Inundation)

Q&A: History Will Condemn Today’s Leaders for Inaction

The building industry’s main critique of CEQA is that it is abused by opponents of development. Industry lawyers tell stories of “not in my backyard” neighbors tying up or derailing what they call perfectly benign projects with what developers consider picayune complaints about auto traffic, wind patterns or shadows cast in parks.

Major local industry players, such as the Bay Area Council and Bay Planning Coalition, supported the effort to dismantle key portions of the law. “Requiring developers to account for external environmental impacts on projects was never the intent of CEQA and would mark a profound and fundamental change in the law, creating unreasonable and extremely costly barriers to infill development that is our best opportunity to address our housing crisis,” said Rufus Jeffris, vice president of communications at the Bay Area Council.

The push-back on the use of CEQA to address climate change, however, goes a step beyond the usual complaints by neighbors. In its Supreme Court case, the California Building Industry Association argued that the law “really is not the right tool” to address sea level rise. Andrew Sabey, an attorney with Cox, Castle & Nicholson, who represented the association, said cities do not need state law to do their jobs.

“There is a robust world of planning and zoning law, a robust world of federal or state laws that can be considered,” Sabey said.

Cities, he said, “should be doing planning and exercising their police powers. It goes back to the analogy that isn’t perfect: A lot of legislative muscles were allowed to atrophy. You have planning law. You should be using it.”

But Chris Kern, a city planner in San Francisco, said that for years his office relied on CEQA to regulate private development threatened by flooding, and that no existing local ordinances allow him to require changes to developments that may become unsafe as the bay rises and storm related flooding becomes more frequent.

Some environmental lawyers who use CEQA to challenge developments worry that real estate interests are passing off costs to the taxpayers. Government agencies could be on the hook for protecting poorly defended buildings that they are still permitting for construction.

“It’s so wrong,” said Doug Carstens, a managing partner of Chatten-Brown & Carstens, a law firm based in Southern California that represents environmental and community groups. He said developers are arguing that a problem exists — but it is no longer their problem.

“People have these concerns and want answers, and developers are saying, ‘We don’t have to give you an answer,’” Carstens said. “It’s putting blinders on.”

According to Richard Frank, director of the California Environmental Law and Policy Center at the University of California, Davis, developers are working hard to consolidate their state court victory. “They will continue to argue for a limited application of the California Environmental Quality Act whenever they can,” Frank said.

Basketball by the Bay

The waterfront’s latest marquee project — the future San Francisco home of the Golden State Warriors basketball team — broke ground in January.

The project, which includes the arena and a nearby office complex, sits directly across the street from San Francisco Bay and a few feet above the current level of the water. (The exact height has changed in successive drafts of the architectural renderings.) When it opens for the 2019-2020 season, the newly christened Chase Center will anchor the city’s 303-acre Mission Bay neighborhood, south of downtown, where new offices, medical campuses and residential buildings are rising every year.

In March, Uber Technologies announced that it had acquired a significant stake in two office towers within the arena project, and that thousands of employees would occupy half of the 580,000 square feet of office space.

The Warriors’ last environmental report, approved in 2015 by the Planning Commission, acknowledged that sea level rise could get bad enough to flood plazas and the arena’s basement during a storm in 2100.

Possible remedies include berms around the perimeter or, in a pinch, strategically placed sandbags. (For more on San Francisco’s sea-rise planning in Mission Bay, see Projects Sailed Through Despite Dire Flood Study.)

Despite these challenges, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee remains a champion of the arena, which he has called his “legacy project.” He stood alongside executives and basketball players to plunge a ceremonial golden shovel into a dirt pile at a groundbreaking ceremony on Jan. 17. The team defeated a bitter legal challenge in November by arguing, in part, that CEQA no longer required the team to protect against environmental impacts such as sea level rise and wind.

San Francisco City Attorney Dennis Herrera celebrated the rigorous legal defense in a press release: “A small group of opponents had threatened to litigate ‘until the cows come home,’ despite losing in court every step of the way,” he wrote. “Well, guess what? The cows have come home.”

This is a crucial moment for environmental planning in California. Last fall, Brown declared California would lead the battle to prepare for the effects of climate change. In a fiery speech in San Francisco’s Moscone Center before thousands of scientists, Brown said California would step in where Washington had failed to do the right thing.

Policies articulated by the Trump administration have focused on reducing funding for some of the programs most cherished by California environmentalists. One such grant is the S.F. Bay Water Quality Improvement Fund. It is a major contributor to a 50-year wetland restoration project that is expected to cost $1 billion, from a mix of federal, state and local sources. Last summer voters across the Bay Area passed Measure AA, which levies a $12-per-parcel tax to pay into the fund.

Responding to threats to defund NASA’s Earth Science division, Brown issued a headline-grabbing one-liner: “If Trump turns off the satellites, California will launch its own damn satellite.”

But land-use regulation is generally less high profile than energy policy or climate research. More than a year after the state court ruling, the state has not given much help to local governments. The Office of Planning and Research, which Brown oversees, has proposed new guidance for local governments on how to interpret CEQA in light of the court’s ruling. But an early draft suggests that it will not recommend that cities or courts continue to use CEQA as a regulatory tool to address climate change.

In November, the California Building Industry Association sent a letter to the planning agency requesting that any new rules include direct language from the court’s opinion. In January, the planning and research office posted the letter online after the Public Press filed a public records request.

Brown has criticized CEQA since at least 2012, and called for local land-use policy to be streamlined. The reform, he said, was “the Lord’s work.”

Last year, he pushed for the deregulation of new market-rate developments that included affordable housing. Brown’s proposal to award these projects approval without environmental review — the so-called as-of-right provision — faced fierce opposition from environmental and labor groups and failed to win support in the Legislature.

Local Response Muted

In summer 2015, the Public Press calculated that Bay Area builders had invested more than $21 billion in 27 major new shoreline developments in areas vulnerable to sea level rise. Records showed that in San Francisco alone, scores of smaller buildings in the Financial District, Mission Bay and South of Market could also end up under water. (For articles and interactive maps, visit sfpublicpress.org/searise.) While many cities touching the bay said they were studying the problem, few had set any limits on development, such as zoning and building codes.

San Francisco Planning Department officials said at the time that they required developers to raise the land or set buildings back. Using the reporting process outlined by CEQA, planners provided developers with a checklist that included a review of the effects of future flooding and references to the most up-to-date sea rise predictions. Kern, the senior planner, said CEQA was a nimble tool that could adapt with the changing science. But after the ruling, while the department could encourage developers to address rising seas, it could no longer force them to do so.

Kern said cities might need to adopt new regulations. “That is something that we have been discussing in the city for some time,” he said. A committee convened by the mayor last year said that any such proposal would come by 2018 at the earliest.

Sea level rise was not the focus of the state Supreme Court ruling. At issue were strict pollution standards for allowing development in areas with dirty air. The ruling criticized what lawyers called the “reverse application” of the state law: “Agencies generally subject to CEQA are not required to analyze the impact of existing environmental conditions on a project’s future users or residents.”

That wording left many planners, developers, lawyers and policymakers confused about the circumstances in which climate change might be relevant. Lower courts may bring more clarity by ruling in future cases in which developments “exacerbate existing environmental hazards.”

Ellison Folk, a partner in the environmental firm Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger, represented the Bay Area Air Quality Management District in the case. She said the ruling created a “gap” in regulation. “I think agencies have the ability to do this kind of analysis and regulate to address sea level rise,” she said. “You can still use the CEQA process as your vehicle for doing that — because the Supreme Court said that if you want to do that, you can. There’s just nothing that requires you to.”

Without new state or local laws, many environmentalists place their hopes in regional planning. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission, which was formed 50 years ago to stop developers from filling in the bay, voted in October to create a region wide climate adaptation plan. But the agency’s own land-use jurisdiction is limited to 100 feet inland from the shoreline, so its challenge will be to cajole normally competitive cities to work together.

Larry Goldzband, the executive director, said that with water now creeping inland, cities on the shoreline will face hard choices.

“Everybody in the Bay Area who deals with planning, or is a planner, or has to work with planners recognizes the bay is going to get bigger, and we have to figure out how we’re going to prosper in spite of that,” he said.

One unfortunate possibility, he said, is abandonment of the lowest-lying ground: “Retreat may well become necessary.”

Developers Begin Legal Challenges

The “reverse application” of CEQA first came under scrutiny in a 1995 appellate court case, Baird v. County of Contra Costa, which centered on an addiction treatment organization that planned to add a 20-bed treatment center for teenage boys. Neighbors sued, saying nearby land was contaminated with petroleum in open ponds at a former Shell Oil plant. The court held that a developer did not need to consider how existing toxic hazards might affect new residents. “The purpose of CEQA is to protect the environment from proposed projects, not to protect proposed projects from the existing environment,” the judge wrote. But this case was considered an outlier and was not relied on as precedent. Lawyers and judges largely ignored its arguments for more than a decade.

Then in 2009, conservative appellate courts in Southern California began repeating language from Baird. In City of Long Beach v. Los Angeles Unified School District, another court held that CEQA did not require the district to mitigate the effects of toxic air pollution when constructing a school close to a freeway.

In South Orange County Wastewater Authority v. City of Dana Point in 2011, the Court of Appeal held that CEQA did not require residents of a proposed subdivision to mitigate odors from a wastewater treatment plant. “The Legislature did not enact CEQA to protect people from the environment,” according to the ruling.

Sea level rise first came under consideration in Ballona Wetlands Land Trust v. City of Los Angeles in 2011. Developer Playa Capital wanted to build condominium and commercial space on a wetland in Los Angeles. The land trust sued, saying the developer did not adequately “discuss impacts relating to sea level rise as a result of global climate change.”

Again borrowing language from Baird, the court argued that CEQA did not apply. The purpose of state-mandated environmental impact reports, it said, “is to identify the significant effects of a project on the environment, not the significant effects of the environment on the project.” After Ballona, some Bay Area developers similarly argued that they no longer had to offer engineering solutions to climate related flood risks.

In 2012, Facebook submitted designs for its new 430,000-square-foot headquarters in Menlo Park, parts of which were just a few dozen yards across from — and a few feet above — San Francisco Bay. The documents claimed that structures would be “raised above future flood risk.”

But officials from the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, the city of East Palo Alto and Save the Bay found the plan to be “inadequate” and asked for “possible options for providing adequate flood protection.”

Facebook followed the anti- CEQA lawyers’ script on how to challenge the law’s authority. Quoting Ballona, the company argued that the review process required developers to “evaluate the effects of the project on the environment, not the effect of the environment on the project.”

The answer satisfied the Menlo Park City Council, which approved the project. The facility opened for business in March 2015.

Late last year, Menlo Park changed its general plan, proposing new transportation and significant building in the neighborhoods of Belle Haven, Flood Triangle, Suburban Park and Lorelei Manor. During public comment, one resident challenged city planners to “detail the number of new residential units and the amount of nonresidential square footage that would be added in areas prone to sea level rise.”

The city responded that it required new development to be elevated 2 feet above the level that the Federal Emergency Management Agency now considers part of the flood zone — a standard that the agency has never updated to account for sea level rise predictions.

Like private development lawyers, the city echoed the recent court cases: “The environment’s effects on a proposed project, which includes sea level rise, are not considered impacts under CEQA.”

A similar fight emerged around a shoreline garbage dump in Marin County. A San Anselmo-based environmental group, No Wetlands Landfill Expansion, filed suit in mid-2012 challenging the state-approved enlargement of the Redwood Landfill in Novato, the largest such facility in the county.

The landfill is near San Francisco Bay and the Petaluma River, and levees would need to be fortified and expanded in five to 10 years. “There is no indication how Redwood must design and construct the levees,” environmentalists wrote. Officials said levees were last expanded in 2008. Landfill representatives said in court filings that Redwood did not want to commit to levee expansion, given the “unknowns associated with sea level rise,” but promised to review and update flood-protection plans every few years. Again, landfill lawyers employed the same CEQA-limiting language as in other cases.

Initially, the appeals court judges were skeptical and agreed to review the climate change analysis. They said that if water breached a levee, thousands of pounds of solid waste would pour into the river and ultimately the bay. This would clearly be “an impact on the environment.”

But after reviewing the company’s planning documents, the judges ruled in favor of the landfill, saying they trusted the company to review levee improvements every five years for “the entire remaining operating life of the landfill.”

Redwood Landfill staff did not respond to requests for comment. Rebecca Ng, deputy director of Marin County’s environmental health department, said the expansion had not begun.

Lawyers Strategize Next Moves

The court rulings have strengthened the hand of lawyers working for the building industry, who gathered several times in the last year to plan their next moves on behalf of developers.

On Oct. 5, 2016, the Bay Planning Coalition, whose mission is to convene industry and municipal groups around development and watershed issues, held a meeting billed as an “expert briefing” at the law office of Wendell Rosen Black & Dean in downtown Oakland. CEQA experts distributed case summaries with key conclusions and language that could be worked directly into environmental impact reports. The main agenda item addressed the nuances of the 2015 California Building Industry Association ruling from the state Supreme Court. Planners and policymakers from local governments were invited.

Sabey, the building industry association lawyer, works at 50 California St. in San Francisco, which attorneys jokingly call “CEQA headquarters,” where the political sausage of Bay Area real estate development is made.

While lawyers on other floors of the building — which has sweeping views of the bay, including hundreds of acres of land that could someday be below sea level — may disagree, Sabey said cities have relied too much on the California Environmental Quality Act.

“There will be that case where sea level rise is a CEQA issue,” he said, “but it should be a rare bird, where you are causing an impact because of your project.”

Subramaniam Vincent contributed data analysis to this report. The story was updated to include details about wetland restoration programs in San Francisco Bay.