Late on Saturday night, phones across the region buzzed with an Amber Alert: Someone had stolen a silver Honda Odyssey with two kids, ages 1 and 4, still inside. Police ultimately found the van and the kids were returned home safely. Their father, Jeffrey Fang, had been making a DoorDash delivery, and told the San Francisco Chronicle he doesn’t make enough to hire a babysitter, and that day care hours don’t coincide with peak food delivery times, when earnings for gig workers can increase. DoorDash issued a statement saying on average, San Francisco Dashers earned more than $39 per hour in January. The incident set off a wave of criticism about what it takes to make ends meet as a gig worker.

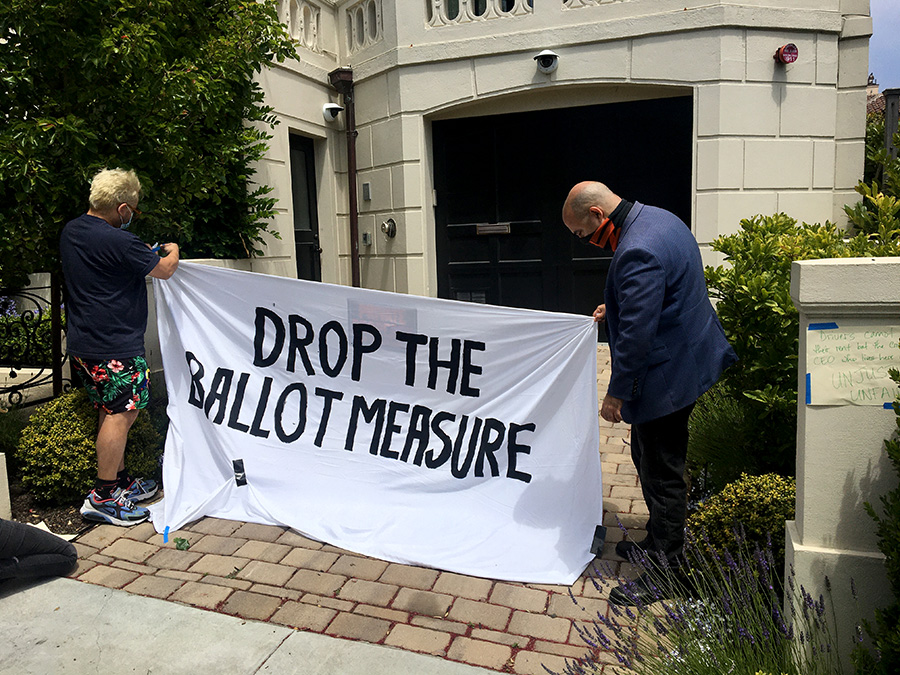

Last year’s Proposition 22 allowed companies that dispatch app-based workers to continue considering them independent contractors, while adding some limited worker benefits. Veena Dubal, a professor of law at UC Hastings who conducts ethnographic and legal research on the gig economy, relays workers’ experiences and examines how it might lay the groundwork for other industries to shift toward gig work on “Civic.”

“It legalizes a piece work system, a piece pay system for the gig economy,’’ Dubal said of Proposition 22, because independent workers are only paid for the time when they are actively being engaged for hire, even if they spend hours making themselves available to the platforms that dispatch them.

Though data about how exactly delivery and ride-hail drivers spend their time is not readily available, Dubal said researchers have found that only a small portion of drivers work on the apps full-time. But that small proportion of drivers work a disproportionate share of gigs administered by the apps.

“What we have been able to decipher is that the majority of the work that is conducted for Uber and Lyft in California is conducted by drivers who work full time and more than full time,” she said.

Some of those whose primary work is driving for apps, she said, feel trapped by debt, which can include investments they have made into cars that enable them to do their work. In 2017, Uber agreed to pay $20 million to settle with the Federal Trade Commission, which had charged that the company exaggerated how much drivers could earn through its vehicle financing program.

“You end up getting into a situation where you’re working to pay off the car, you’re working to pay off your insurance, you’re working to pay off gas, and sometimes it’s not even clear, particularly for the most precarious workers, how much money you are making,” Dubal said. “For the poorest people, thinking about depreciation on a car is a privilege. Instead, you’re just thinking about, OK, do I have $40 that I can cash out today so I’m not going to be evicted from my place?”

Though she said Proposition 22’s passage has not yet dramatically affected gig workers, Dubal expects that companies will now use their victory with the California ballot measure to advance similar laws, combining a legalization of piecework and a few small worker benefits, elsewhere. Uber’s CEO has already advocated for a federal version of the measure.

“These companies think that they have a blueprint that they can now export to other states,” Dubal said. “What really is keeping me up at night is the fact that this hybrid model now exists. It is on the books, and has the potential to spread.”

A segment from our radio show and podcast, “Civic.” Listen at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays at 102.5 FM in San Francisco, or online at ksfp.fm, and subscribe on Apple, Google, Spotify or Stitcher.