As Moscone Center began accepting new homeless residents from street encampments in recent weeks, residents and advocates expressed concerns about safety at the convention center and other group shelter settings.

Three residents said COVID-19 testing prior to admittance at Moscone Center is inconsistent, residents don’t reliably wear masks and sanitation is lacking. Bathrooms were particularly problematic, they said, citing feces-smeared toilet stalls and showers reeking of urine.

“I have yet to see a standardized testing protocol for the reopening of shelters. I don’t know if one exists,” said Brian Edwards, a Coalition on Homelessness organizer and member of the Shelter Monitoring Committee, the city’s homeless shelter oversight board.

“I’m alarmed by the reopening of a congregate shelter for so many reasons, but for them to reopen without a standardized, peer-approved testing protocol is just bonkers,” he added. “If there’s no testing the day of intake, then you have no idea who has what. It just seems like a recipe for disaster — again.”

After an abortive April attempt to turn Moscone Center into a 394-bed shelter for vulnerable homeless residents, the city changed course after leaked images showing a layout with little provision for social distancing caused an uproar. Moscone reopened April 21.

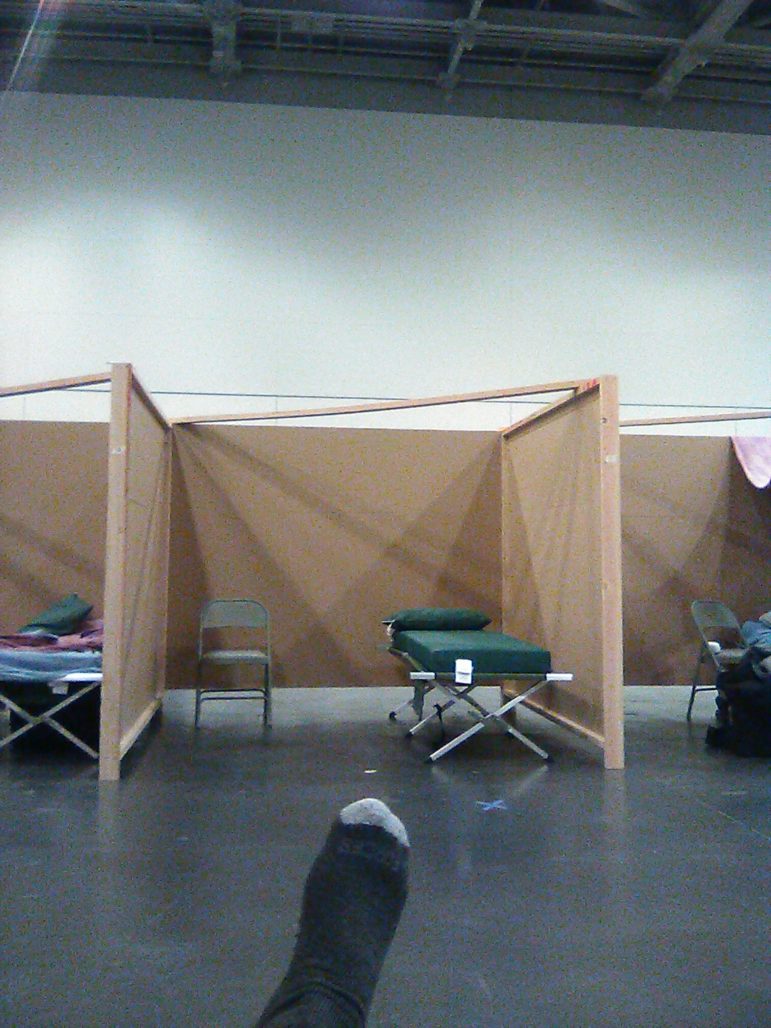

Before it did, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing told the San Francisco Chronicle Moscone would hold no more than 200 people who had tested negative for the virus and undergone a 14-day quarantine period. Officials said all residents would live in small cubicles with walls on three sides to encourage social distancing.

The cubicles went up, but Moscone residents say the testing regimen did not.

Cubicle-like sleeping areas in San Francisco’s Moscone Center are meant to help homeless residents maintain social distancing. Photo Courtesy Richard Steenson

In recent weeks, officials from the homelessness department have repeatedly said the city would reopen group shelters at reduced capacities using a new set of guidelines developed by the Department of Public Health. The guidance does not outline how often shelters should test residents or whether residents should be tested before admission to a shelter.

Since July 6, the Public Press has made multiple requests to the homelessness department and the Department of Emergency Management for further details of the city’s plans, including proposed reopening dates, testing regimens, mask and bed spacing requirements, and other safety precautions that reopening shelters will be required to follow.

“We will not be expanding to our pre-COVID capacity but are looking at safe capacity expansion to help people living unsheltered access shelter,” the emergency department said in a July 20 statement, adding that the Department of Public Health was working to ensure all recommended pandemic safety protocols were followed at shelters.

The department did not answer questions about testing, mask and social distancing requirements, or other safety precautions planned for reopening shelters.

Health department spokeswoman Jenna Lane said her department recommends shelters follow federal Centers for Disease Control guidance on shelter testing, which dictates that shelter residents “do not need a negative test result in order to enter a shelter,” she said, adding that the department recommends monthly and biweekly testing for residents and staff, respectively. “Daily symptom screening, face covering and distancing are most important.”

Lack of testing

After he contracted coronavirus in March while living at Multi-Service Center South homeless shelter, the city moved Richard Steenson into a hotel for three weeks before transferring him to Moscone, he said.

“I was not tested for antibodies nor was I given a test for the virus before I left” the hotel, he said, adding that he received temperature and blood pressure checks instead. “There’s been no medical attention whatsoever since I’ve been in there.”

Delonzo Gallon and Isaiah Glenn, who became residents at Moscone Center within the last six weeks, said that when they moved in, they had not been tested for COVID-19 for at least a week, meaning they could have contracted undetected infections between testing and their entry into the shelter. Everyone who enters the building receives a temperature check and many staffers attempt to enforce mask and social distancing guidelines, but none of them has received a test since moving into Moscone, all three Moscone residents said.

“I can’t say exactly what it is right now,” said Steve Good, CEO of Five Keys, the nonprofit that runs Moscone, of the shelter’s resident testing regimen. “To the extent we can, we’re pretty much on top of it.” He added that staff get tested biweekly.

Test results are only useful at the moment of the test and residents could easily catch the virus after taking one, Good said.

Other group shelters taking in new residents have similar testing policies.

Newly admitted residents at the Division Circle Navigation Center at the edge of the Mission and SoMa did not always have their coronavirus test results before entering the shelter, Shari Wooldridge, executive director of the St. Vincent de Paul Society of San Francisco, the group that runs the center, said in a July 8 interview. The shelter reopened in early May after shutting down for several weeks when two residents tested positive for COVID-19.

“We don’t want to keep people on the streets just because they’re waiting for a test result,” Wooldridge said, adding that residents could be exposed to the virus while awaiting their results. “If they’re not showing any symptoms, then they’re scheduled to get tested once they’re inside.”

Navigation center residents and staff get monthly and biweekly tests, respectively, and staff check the temperature of everyone who enters the building, Wooldridge said. As of July 8, there were about 70 residents at the shelter — less than half its pre-COVID capacity — and the shelter had begun to accept new residents from street encampments referred by the health department.

Outbreak likely? The view from inside

Most of the residents at Moscone wear masks while inside, except the new arrivals from street encampments who began to show up in recent weeks, Steenson said.

“They are far less inclined to wear masks consistently,” he said. “You see guys all times of the day or night without their masks.”

Many of his fellow residents leave during the day to spend time with others who do not live at the shelter and neglect to wear their masks when they do, Steenson said, adding that he thought an outbreak at the shelter was likely if conditions didn’t change.

A toilet stall wall smeared with feces at Moscone West homeless shelter. Photo Courtesy Richard Steenson

“Everyone does not wear masks all the time,” Gallon said.

Staff at Moscone encourage every resident to wear a mask and to socially distance but those rules are “impossible to fully enforce,” Good said.

“It’s really hard to get compliance with every person,” he said. “You can’t just enforce it without having to kick people out.”

Enforcing 24/7 mask requirements at the shelter had also proven difficult at the navigation center, according to Wooldridge. “I know there is a challenge with people sleeping in them” she said.

Moscone’s sanitation and safety challenges

“The bathrooms are not at all being sanitized properly,” Steenson said of Moscone. “The showers are absolutely disgusting. They don’t clean out the gray water tanks frequently enough so that they reek of urine.”

He described toilet stalls smeared with feces and a syringe disposal bin ripped off a wall, stuffed into a sink and filled with water and dirty needles. Gallon and Glenn agreed that the Moscone showers smelled of urine and the bathrooms were often dirty.

All three said fights and theft were common there. A bandage taped to Gallon’s head covered a gash he received in a scuffle with another resident, he said. Another recent fight ended in a resident receiving a serious eye and head wound near his cubicle, Steenson said.

“It’s not a safe place,” Glenn said. “They really should be doing a much better job.”

Delonzo Gallon at Moscone West homeless shelter on July 20. He said he suffered a head injury during a scuffle inside the shelter earlier that day. Brian Howey / Public Press

While security and staff worked at all hours to clean and sanitize the shelter, mediate conflict and protect residents from harm, it was a constant challenge to do so, Steve Good said.

“We realize this is an imperfect system,” he said. “But staff are going out of their way to make it as pleasant as possible.”

Contradictions in coronavirus planning

Advocates and public health experts expressed concern for shelter residents’ safety in March, just three weeks before one of the largest shelter outbreaks in the country occurred at Multi-Service Center South, San Francisco’s largest homeless shelter. Some of those same advocates feel the city is repeating its mistakes by reopening shelters, even at reduced capacities and in concert with stringent health guidelines.

In lieu of housing all of the city’s unsheltered homeless residents in hotels, which Mayor London Breed made clear was not in the cards due to staffing shortages and budget shortfalls, many advocates have pushed instead for more sanctioned, open-air tent encampments,which they say are far safer than large indoor shelters.

A shower at Moscone Center. Photo Courtesy Richard Steenson

Deb Bourne, who directs the health department’s homeless efforts, told the San Francisco Chronicle that sleeping outside is likely safer than crowded indoor settings like homeless shelters and that a tent was an important barrier between unhoused residents and the virus.

Advocates like Brian Edwards said that logic should be reflected in the city’s homeless shelter initiatives: if the city won’t house homeless people in hotels, it needs to take advantage of the 42 potential sanctioned tent sites it identified in June before resorting to indoor shelters.

The city’s decision to ramp up group shelters while pausing indoor dining and other reopening plans betrays a contradiction in the city’s coronavirus planning, said sociology Ph.D. candidate and visiting fellow at Harvard University Chris Herring, adding that current guidelines just aren’t enough to catch the virus before it ripped through another shelter.

“Temperature checks miss a lot and there’s so much asymptomatic spread,” he said.

Almost all of the Multi-Service Center residents who tested positive for coronavirus during the outbreak showed minor symptoms or none at all, the San Francisco Chronicle reported in April, and a study of the prevalence of COVID-19 infections at a Boston homeless shelter found that nearly 88% of shelter residents who tested positive for the virus were asymptomatic.

To Herring and other advocates, the study proves the need for rigorous testing at shelters.

“Now we’re opening up congregate shelters again when the facts on the ground haven’t changed,” Herring said. “It’s like schools: no one wants to keep their kids at home anymore, but we have to make sure it’s safe.”