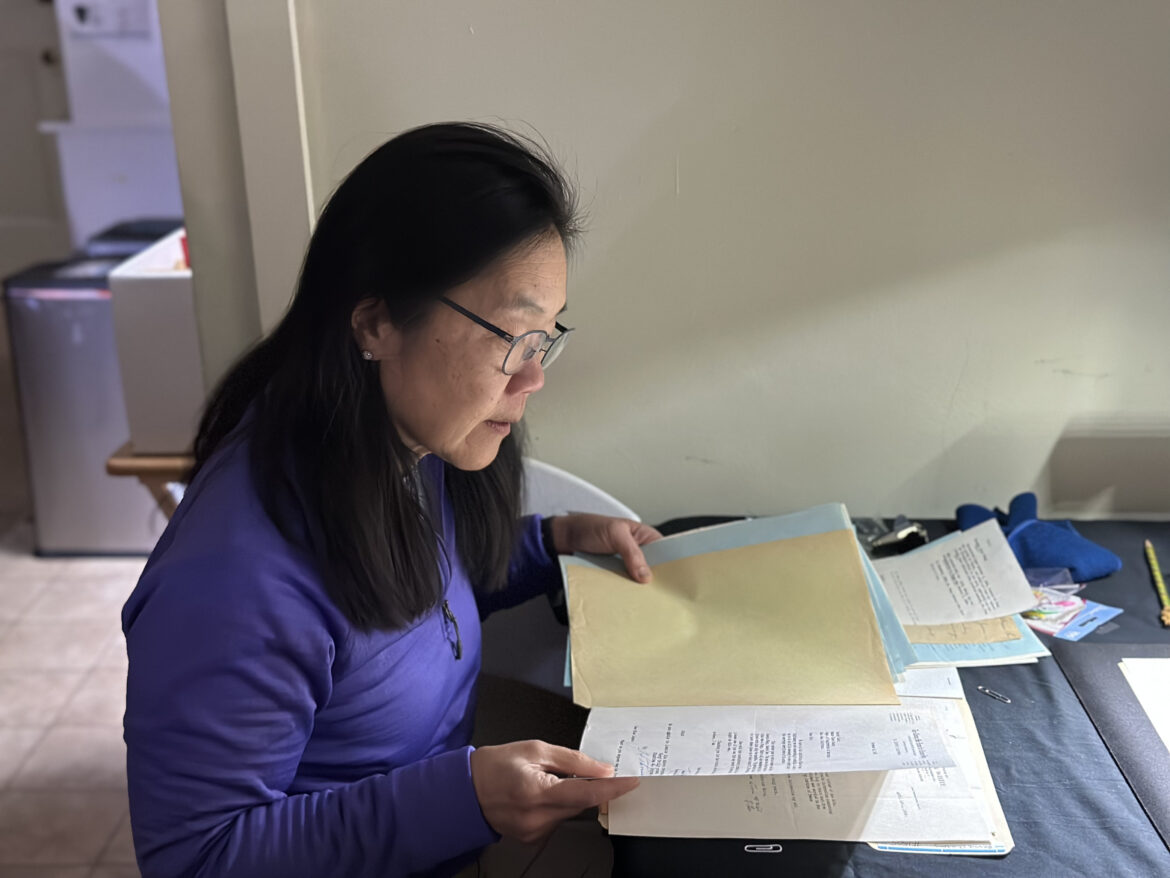

Having grown up as a kid in the Cameron House Youth Program, Joyce Tom was familiar with stories about Donaldina Cameron’s efforts to protect Chinatown’s women and children from being kidnapped and sold in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Yet for years, Cameron remained more of a tale than a real person in Tom’s mind. Until this Monday, when she stumbled upon pages of Cameron’s handwritten notes while digitizing century-old records stored at Cameron House, one of the oldest organizations in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

“It felt like stepping through a door into the past,” she said.

Tom is part of a volunteer group, led by community historian David Lei and University of California, Berkeley lecturer Anna Eng. They are working on a week-long project to scan boxes of documents — memos, letters, photos and other archived items.

The scanning project is a collaborative effort between historians striving to increase access to alternative historical sources and community organizations wanting the history to be restored and told.

The physical copies will be preserved at UC Berkeley, where researchers from around the world will have easy access to them.

Race Against Time

Community organizations often have limited capacity to store and preserve archives with proper temperature and climate control, especially when they are handling a hundred years’ worth of fragile records. The digitization project is a race against time, as many originals have deteriorated or been lost.

The team recently finished digitizing a portion of the archive for another organization in Chinatown, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, also known as the Six Companies.

Established in the 1850s, it was once regarded as Chinatown’s City Hall and was known for helping newly arrived immigrants. It played a pivotal role in many civil rights lawsuits against the Chinese Exclusion Act, notably the 1898 Wong Kim Ark case, which established birthright citizenship in the United States.

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association retains a significant trove of records such as meeting minutes and letters, revealing how Chinatown leaders aided members facing immigration challenges and detention. Until the recent document scanning session, many of its century-old source materials had not been thoroughly studied by historians and were at risk of deterioration.

Boxes of records were stored in a moldy back room and closet. On the second day of the scanning process, heavy rain flooded the floor where the boxes were stored. “Luckily, we were there,” said Lei. “The very reason why we need to scan it is just in case no one was there when the flood came.”

Digitizing archives is just the first step of preservation. Lei’s goal is to encourage organizations to protect original copies by sending them to a major institution to assist in long-term archiving and preservation.

Untold History

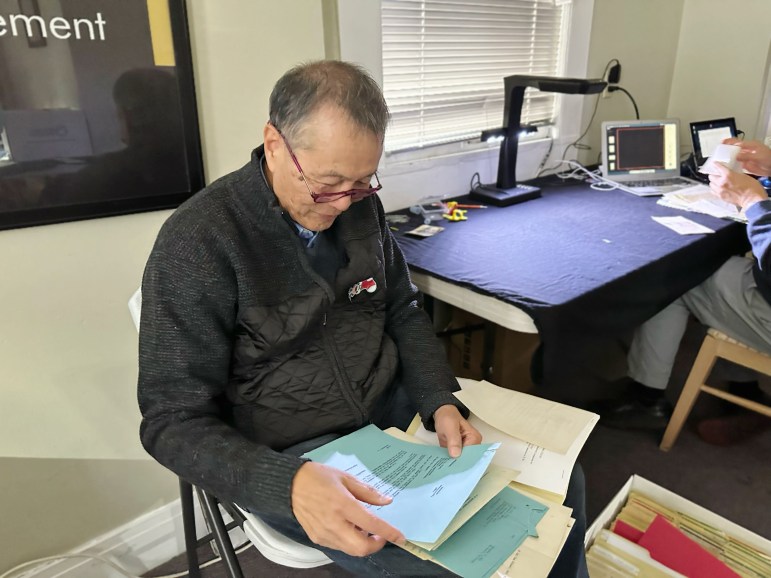

Lei, the community historian, has a passion for traditional Chinese culture. Upon retiring and selling his consumer product sourcing company in 2003, he shifted his focus to studying Chinese American history, which had been a longtime interest.

Zhe Wu / San Francisco Public Press

David Lei, who leads the scanning team, sorts files in chronological order before scanning.Lei noticed gaps in existing writings on Chinese Americans, as the sources he found often did not capture the full range of experiences, nor details about the regions and ethnicities of those who first immigrated to the U.S. Limited records from the first 50 years of Chinese immigration led historians to rely heavily on unreliable sources, like articles published in English-language newspapers.

Eng echoed Lei’s concern: “As historians, we cannot write the history, or we cannot write a different history, if we cannot access new sources that will add more complexity to the story.”

San Francisco is home to several organizations that played key roles in Chinese American history. Many lack digital copies of their own archives. Scholars sometimes seek access to the physical copies, but coordination challenges often lead these groups to decline such requests.

Having grown up in Chinatown, Lei stays connected with the community, which helps him initiate conversations about records conservation. He started the scanning project on a smaller scale with friends before expanding it to include the two oldest entities in Chinatown.

Zhe Wu / San Francisco Public Press

Volunteers scan records on the third floor of Cameron House in San Francisco’s Chinatown.While sorting through files about women rescued at Cameron House, Tom discovered details that both amazed her and shifted her perspective. “These are all cursive,” she said, pointing to the letters likely written by women who were English learners. “For them to have perfected this language to the level of these writings is impressive,” she said.

It may take time for the Cameron House archive to become public and open to closer examination, but progress is underway.

The One-Point-Five Generation

Lei said many volunteers he has recruited are retirees with valuable cultural and language competencies. Their expertise is crucial in the archiving process, especially in identifying and recording dates.

“There’s a lunar calendar, a Republic of China calendar and a Western calendar,” explained Gregory Li, an experienced volunteer who is well versed in Chinese history.

Zhe Wu / San Francisco Public Press

Gregory Li and another volunteer work together to scan files.Li, a retired lawyer, was born in America and can fluently speak and write Mandarin, Cantonese and Taishanese. He and other volunteers are what Eng would describe as “one-point-five generation” — those with strong connections to both their American communities and the immigrants who brought their families here.

The pattern of Chinese American migration has changed over time. Many early waves of immigrants came to San Francisco from Cantonese communities in and around southern coastal China. Eng said that members of the one-point-five generation often relate to the history of these groups because many of their families also came from that region or speak the same dialects.

Parts of Eng’s family have lived in the United States for five generations, but some relatives, including her mother, were kept out of the country under the Chinese Exclusion Act until an immigration law change in 1965. This personal connection fuels her commitment to ensuring that records from the era are preserved, and that this part of the community’s collective memory is not lost.