There will be a brand new dragon in this year’s Chinese New Year Parade finale, celebrating the Year of the Dragon.

The parade’s organizer, the San Francisco Chinese Chamber of Commerce, has announced the roster of floats and entertainers who will participate, including a 289-foot golden dragon that debuted in public on Lunar New Year’s Day, Feb. 10, for a Taoist “awakening” ceremony.

Typically, the dragon is replaced every six to eight years, said Harlan Wong, the parade director and a board member of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce. The most recent dragon, purchased six years ago, suffered damage during last year’s parade, due to inclement weather.

Zhe Wu / San Francisco Public Press

Harlan Wong, director of San Francisco’s Chinese New Year Parade, said Wong said organizers felt it was time to refresh the parade’s most iconic feature — a golden dragon that volunteers will carry in serpentine fashion along the parade route.While it could probably still be used, Wong said, organizers felt it was time to refresh the parade’s most iconic feature: “We want it to coincide with the year, to bring out a dragon in the Year of the Dragon.”

To celebrate the Year of Dragon, San Francisco’s Chinatown is hosting several art and cultural events as part of its Lunar New Year celebrations. These range from traditional activities, such as the flower market, to new initiatives like a pop-up store featuring Asian American artists at the Chinatown-Rose Pak Station, Muni’s newest Central Subway metro stop.

The passing of the golden dragon is the centerpiece of the annual procession. Following exquisite floats, costumed dancers and marching bands, a large team will maneuver the long, illuminated dragon down the parade route, concluding the Chinatown tradition for Lunar New Year.

The Chinese New Year Parade, the festival’s pinnacle event, is scheduled this Saturday. Until then, the new dragon is on display at Three Embarcadero Center.

Parade as a Public Expression

Chinese Americans have used parades to exhibit their culture and broadcast messages since the 1850s during California’s Gold Rush Era.

Chinese Americans participated in some of California’s earliest parades, including a San Francisco funeral procession for President Zachary Taylor in 1850.

Local newspapers first reported large dragon dance ensembles on San Francisco streets during Year of the Monkey celebrations in 1860. But the first well-documented parade in San Francisco’s Chinatown took place in 1887. It was organized by Yeong Wo Co., a district association that served immigrants coming from the same hometown in the Zhongshan area, Guangdong Province, near China’s southern coast. “We know that they imported a dragon and they had a customs problem,” said Lei. “They sued the government for lower duty and lost.”

Courtesy of David Lei

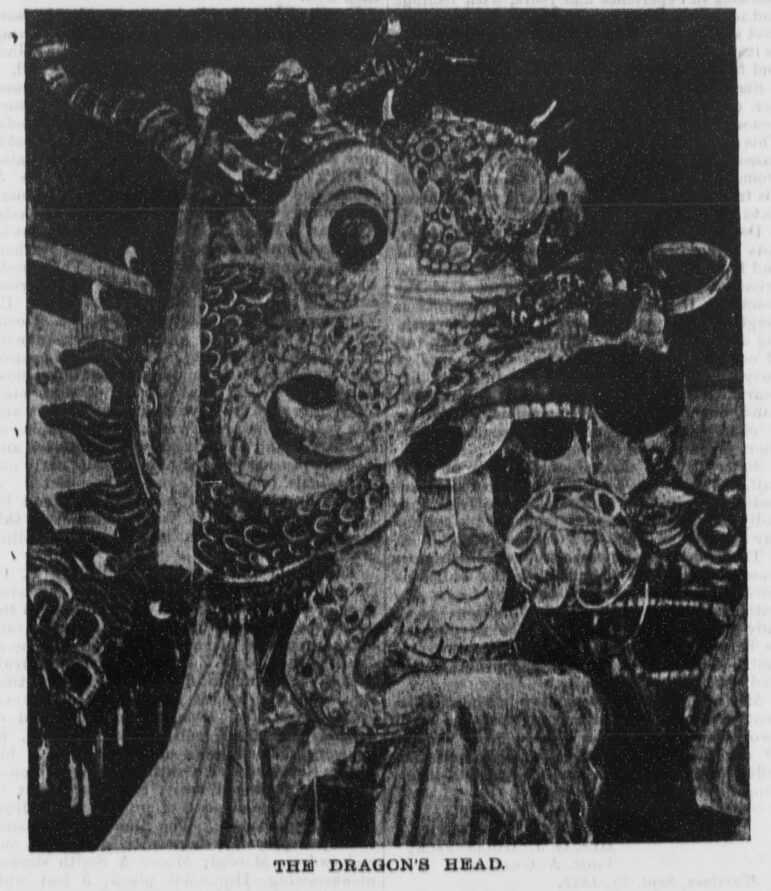

David Lei provided a copy of a news clipping featuring an early Chinatown parade dragon from an Oct. 8, 1887, edition of the San Francisco-based Pacific Rural Press.David Lei said association members could have won their case but they didn’t have time to spare so they paid the import tax to meet their own August festival deadline.

Lei explained that the parade, dedicated to Hau Wong, a deity worshiped in Southern Canton, China, carried a significant message to the Chinese community beyond its religious implications. Parade participants associated Hau Wong with a loyal Song Dynasty general. Therefore, the celebration of this deity could symbolize a desire to restore Han Chinese rule.

For most non-Chinese spectators of the 1887 parade, the dragon procession and Chinese opera performances were the highlights. The parade drew high praise in local newspapers.

For decades, the Chinatown community organized parades for various causes, including elevating the neighborhood’s reputation, protesting discrimination and raising funds for charity, including for people in China whose lives were in turmoil during World War II.

Taking over the Narrative

When Chiou-Ling Yeh first researched the Chinese New Year Parade for her PhD dissertation 20 years ago, she was amazed. Originally from Taiwan, Yeh said parades are “more of an American tradition. In China, they don’t do a parade for the Chinese New Year.”

Hong Kong hosted its first Chinese New Year Parade in 1996, drawing upon the experience of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

The modern form of San Francisco’s Chinese New Year Parade took shape in 1953, when H.K. Wong, a Chinatown businessman and director of San Francisco’s Chinese Chamber of Commerce, decided to promote the Lunar New Year celebration to the rest of San Francisco.

Wong was the first reporter in Chinatown and served as marketing director for the renowned Empress of China restaurant. Frustrated by the way most local newspapers covered Chinatown, often focusing on gambling arrests, he opened up the previously private celebration, hoping to reverse the bad press.

In an interview featured in the book “Longtime Californ’: A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown” (Stanford University Press), he said: “I thought this would be the appropriate time to invite our American friends to share in this happiness and to appreciate and learn things about Chinese.”

It was during the Cold War, when Communist China was perceived as an enemy. The parade served as more than just an ethnic festival. Featuring Chinese American veterans from World War II and the Korean War, it demonstrated Chinese Americans’ patriotism and loyalty to the United States, and their efforts to integrate into mainstream American society.

The parade has evolved. Its route weaves through more neighborhoods, and it has been promoted as a winter tourist attraction since 1963, when the San Francisco Convention and Visitors Bureau signed on as a co-sponsor.

Local television stations began to broadcast the parade in 1988. It soon garnered national and international attention, attracting sponsors and drawing a wide audience.

Being featured on television significantly reshaped the narrative of Chinese Americans. “In the ’60s and ’70s, the only thing you read about Chinese Americans were tong wars, gang killings, and illegal contributions to politics, almost always negative,” Lei said. When the spotlight turned to the parade, organizers seized the chance to present their community in a different light: “We could explain our culture our way,” Lei said.

Evolving Message

Lei recalled that, as a teenager in 1964, he organized a group of friends to carry the golden dragon. Athletes from a martial arts school managed the head and tail, while his team helped carry the segmented body.

“We didn’t even really have to carry the dragon,” Lei said, laughing as he explained how spectators were happy to lend a hand. One person on their crew was designated to look for people in the crowd who wanted to participate. As the team carried the dragon through the streets, when one volunteer got tired, the crowd-spotting coordinator would find a replacement.

Serendipitous moments like that were lost when the parade transitioned into a televised event, Lei said. But new opportunities emerged and the parade evolved to carry new meaning.

“The parade here actually touched upon many issues, in the larger U.S. society and also within the Chinese American society, and also reflecting the issues within the Asian American community,” said Yeh, who later published her dissertation as a book, “Making an American Festival: Chinese New Year in San Francisco’s Chinatown” (University of California Press).

While the parade served as a civic engagement tool for Chinatown, over the years it adapted to reflect broader societal changes, including efforts to advance civil rights, women’s and LGBTQ rights.

Organizers of the Chinese New Year Parade also supported other local communities’ parades, including San Francisco’s world-famous Pride Parade. In 1994, the Gay Asian Pacific Alliance became the first gay rights group to join Chinatown’s iconic parade, and it received enthusiastic support.

Parades continue as a means for communities to convey messages. Following mass shootings in Half Moon Bay and Monterey Park, a new public art project was unveiled at last year’s parade to bring together Chinese and Latina immigrant women designers.

For Lei, the Year of Dragon symbolizes the power of diversity, which he believes is highly reflective of America. In Chinese culture, the dragon is the most powerful mythological creature, with the best part of every animal, from claws of eagle to the body of a snake, he said. “When you absorb the depths of different cultures, you become the most powerful,” Lei said.