San Francisco neighborhoods the federal government targeted with racist lending practices face the greatest health threats from pollution, a recent state study found.

The California Environmental Protection Agency analyzed the latest pollution data in historically redlined neighborhoods, where people of color were denied mortgage loans under federal policies, in the report finalized in August. Those neighborhoods “are generally associated with worse environmental conditions and greater population vulnerability to the effects of pollution today,” said the report, which marks the agency’s first formal recognition that redlining is correlated with pollution.

Environmental groups have welcomed the report, saying its findings could aid their push for policies to reduce those communities’ burdens.

The report should add to the state’s “sense of urgency to move much more quickly to reduce dangerous air pollution from extracting, transporting, refining and burning fossil fuels,” said Laura Neish, executive director of 350 Bay Area, a group pushing for policies that reduce carbon emissions.

Redlining “has concentrated communities of color in areas that harm their health and shorten their lives,” she said. “Cal EPA’s report acknowledges the historical through line, which is the first step to addressing the problem.”

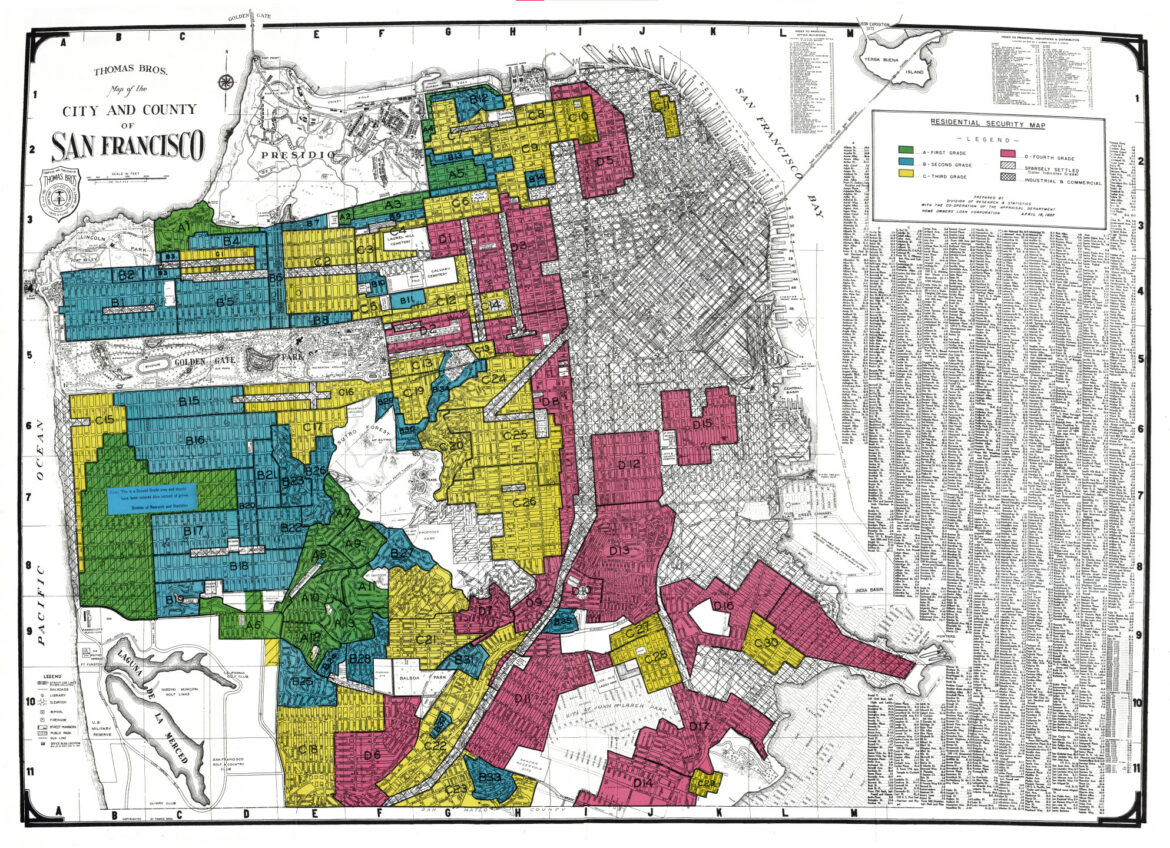

Redlining has roots in the aftermath of the Great Depression. To stabilize the housing market, the federal government authorized the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to rank the desirability of neighborhoods on a four-point scale. Residents of neighborhoods that ranked higher — mostly white Americans — had greater access to low-interest loans to purchase homes.

The government assigned the lowest rankings to neighborhoods with large numbers of people of color, marking these areas in red on maps, a practice that became known as “redlining.” Because residents of redlined areas were less likely to get loans and accumulate wealth through property, this practice expanded the wealth gap that persists to this day between white people and people of color.

For the report, researchers layered maps of redlined neighborhoods over data from CalEnviroScreen, a state tool that measures pollutants and residents’ vulnerabilities to them. In every city, the average pollution burden in redlined neighborhoods was greater than those in neighborhoods the government had ranked higher in desirability. In addition to San Francisco, the review analyzed neighborhoods in Oakland, San Jose, Sacramento, Stockton, Fresno, Los Angeles and San Diego.

The findings show “how embedded, systemic racism in government actions likely contributed to the segregated neighborhoods and environmental injustices we see today,” the report’s authors wrote. “It counters the notion that environmental injustice is due only to income or class.”

Greg Gearheart, who co-authored the report, said he hoped his team’s work would help “normalize” conversations about the intersection of race and environmental justice.

If so, it would make advocacy easier, said Ernesto Arevalo, the Northern California program director at Communities for a Better Environment.

Arevalo, who is discussing with Oakland city staff what kinds of real estate development to allow in coming years, said they have to repeatedly explain to the government the connection between redlining and elevated pollution levels in areas like East Oakland — that redlined areas attracted industrial businesses, which belched pollutants into surrounding communities and drew heavy traffic.

“Explaining ourselves is a lot of work,” Arevalo said, adding that they hope the Cal EPA report will start doing that work instead.

In San Francisco, the report underlines the government’s duty to help residents in the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood reduce their exposure to pollution, because redlining led to that exposure in the first place, said Michelle Pierce, executive director of Bayview Hunters Point Community Advocates, an environmental justice group serving the city’s southeast neighborhoods. For example, the government could help residents replace gas heating systems with electrical alternatives, she said.

“We created this racist burden,” she said, “and we need to just open up our pocketbooks” to pay for the work.