The San Francisco Board of Supervisors is planning to take up a proposal to force owners of soft-story buildings to retrofit them by 2020, said a city official in charge of earthquake safety.

Supervisors Scott Wiener and David Chiu plan to sponsor the ordinance and other supervisors might co-sponsor it by Tuesday, said Patrick Otellini, manager of the city’s Earthquake Safety Implementation Program. The proposal is not yet listed on the board’s agenda.

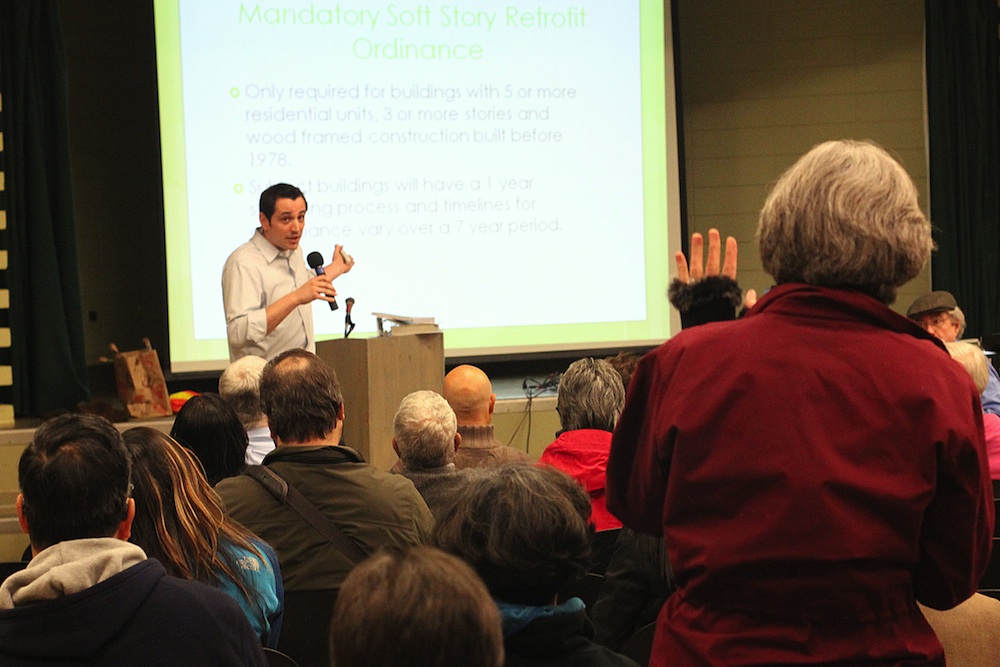

The legislation, which Otellini summarized at a public forum Wednesday, would apply only to wood-frame buildings built before 1978, with at least three stories. Smaller buildings and single-family homes would be exempt.

Finding ways to help landlords finance the repairs has remained a major sticking point ever since the failure of a 2010 ballot measure designed to provide some assistance. Financing questions were “a major reason for the delay” since then, Otellini said.

At a public forum Wednesday organized by San Francisco Fire Department, Otellini said building owners would have several payment options, including a city-sponsored “micro-loan” program and special deals through private banks. He said he was planning to meet with bankers on Friday to discuss how they could work with the city to finance retrofits.

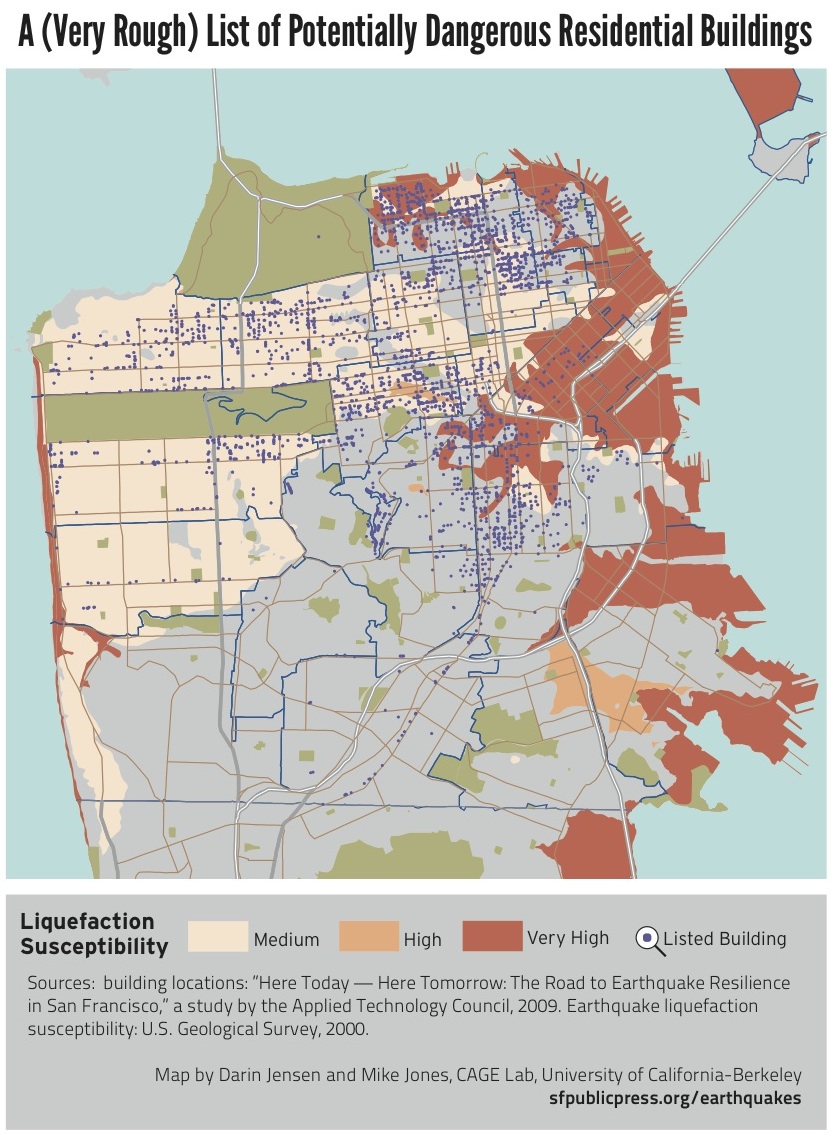

Thousands of people live in potentially dangerous soft-story buildings, according to data that the city has possessed for at least three years but never passed on to building tenants or owners. In December, the Public Press used this data to publish a list of 2,929 potentially dangerous soft-story buildings housing an estimated 58,000 people, or about one in 14 San Franciscans. See: sfpublicpress.org/softstorylist.

In early December, Otellini and former Chief Building Inspector Laurence Kornfield unveiled the ordinance’s basic outline. Retrofits would occur in four phases, they said, with the most vulnerable building types going first. These include soft-story buildings with large restaurants on the first floor or high occupancies, or those standing on soil types prone to liquefaction.

Otellini and Kornfield predicted that if the ordinance passed in 2013, the last phases of buildings would be retrofitted by 2020.

The city has yet to craft policy for smaller soft-story buildings. “There’s currently no mandatory retrofit proposal for one- to two-family dwellings,” Otellini said. But his office is working on a website that would be a “one-stop shop for getting the retrofits done.”

The forum at the County Fair Building in Golden Gate Park touched on a wide range of earthquake safety issues, but questions from the audience focused almost entirely on the challenge of retrofitting soft-story buildings.

Barbara Oleksiw, who owns a two-story building in San Francisco, asked Otellini if she would have to retrofit. Otellini said no, her property did not qualify.

But Oleksiw nonetheless urged fellow building owners to retrofit, even if the new law would not apply to them: “If your house is suddenly devalued by a disaster, you’re going to lose a tremendous amount of equity. You either pay now, or you pay later.”

When one building owner expressed concern that his property was on “the city’s list” of vulnerable soft-story buildings, Otellini said the Public Press’ published list was not the city’s list. He said the city had chosen not to publish such data to “avoid raising alarm” because it had not yet double-checked the list.

Inspectors, engineers and other professionals produced the data for the city in 2009 through an informal visual survey at street level. They have been loath to reveal the locations of buildings to the public until inspectors had the time to verify the data with on-site property investigations.

David Bonowitz, a structural engineer who helped gather the data, said the survey’s purpose was to get an overview of the scope of San Francisco’s soft-story problem, not to warn landowners or residents.

“This kind of survey data is necessary at the very early stages of policy development,” Bonowitz said in an email. “It was important to know, for example, are we talking about 1,000 buildings or 10,000?”

The forthcoming soft-story retrofit ordinance would require property owners effectively to do the double-checking themselves by hiring contractors to do on-site inspections and retrofits if necessary.

The proposal comes almost a quarter-century after the Loma Prieta earthquake showed the vulnerability of buildings with store windows and garages on the ground floor. The magnitude-6.9 quake collapsed seven Marina District soft-story buildings, when weak first floors gave out under the weight of the apartments above.

San Francisco, with more soft-story buildings than any other Bay Area city, has never required owners to inspect their properties for soft-story vulnerabilities. Such requirements have been introduced in recent years in other cities, including Berkeley, Alameda, Fremont and San Leandro. For more on the history of Bay Area retrofits, see the Public Press’ special report, “Bracing for the Big One,” in the Winter 2012-2013 print edition and online at sfpublicpress.org/earthquakes.

The city came very close to mandating soft-story retrofits in 2010, when then-Mayor Gavin Newsom proposed Proposition A to help pay for retrofits on certain building types, including single-room occupancy hotels. The measure failed at the ballot after earning 63 percent of the vote, just shy of the supermajority it needed to pass.

Voluntary measures have not come close to solving the problem. The Department of Building Inspection launched an optional program in 2009. As of last September, only 53 buildings had received retrofits, or less than 2 percent of the estimated 2,800 to 3,000 problematic structures.

Debra Walker, a member of the Building Inspection Commission, expressed frustration with the city’s slow pace of progress. “We’ve been talking about this for quite a while,” she said. “We know what we know. We have to act.”

This story is a follow-up to a package of stories about earthquake safety in the Winter 2012-2013 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press.