Despite assurances from officials that the practice would stop, city workers continue to confiscate homeless people’s tents and remove encampments as the coronavirus spreads across a shuttered San Francisco, according to residents, a city employee and 311 call records.

Just one day after the city announced that it would stop removing homeless encampments in actions known as “sweeps,” removals surged to 31 and continued at an average pace of 16 per day, according to data from 311, the city’s non-emergency complaint line and hub for reporting homeless encampments. In the week before the March 17 announcement that the city would halt the sweeps for the remainder of the COVID-19 crisis, the number of encampments marked “removed” by city employees also averaged 16 per day and dropped to as low as one.

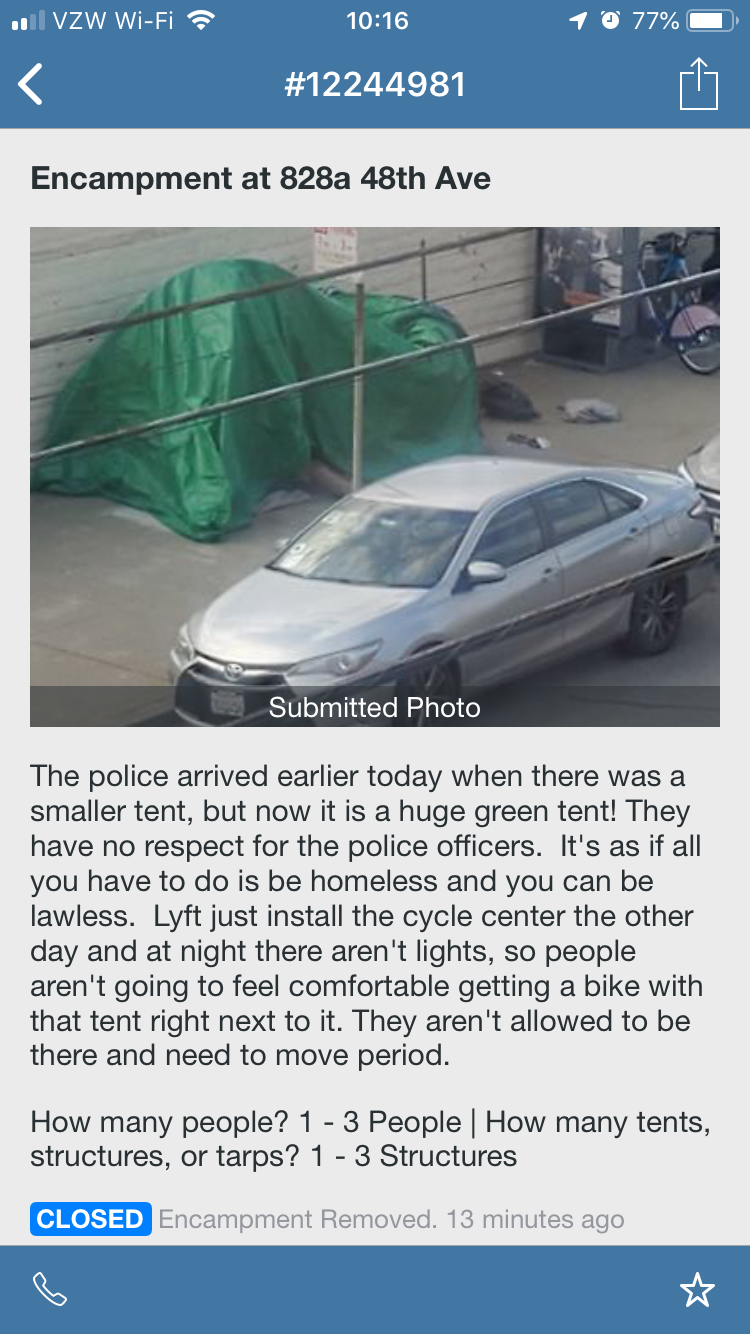

While tent confiscations have declined considerably compared to pre-outbreak times, city workers are still forcing people to break down and move their tents.

A long-time Public Works employee who asked not to be identified due to fears of retaliation wrote in an electronic communication that the department continued to confiscate unattended tents in the Mission and Tenderloin. “Many people leave their property and then if unattended it is picked up,” the employee wrote. “That is called bag and tag and that is still being done for sanitation reasons.”

These confiscations seem to contradict statements from both Jeff Kositsky, former director of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, who announced the sweeps would halt, and Human Services Agency head Trent Rhorer. In a March 23 press conference, Rhorer said the city would follow federal Centers for Disease Control guidelines on how to mitigate the spread of the new coronavirus among unsheltered homeless people.

“Cities should be taking care to allow individuals and keep individuals on the street, to not bring encampments inside where they can infect others or increase the risk of infection,” Rhorer said. “Rather, the guidance is very clear, we should be dispatching teams to ensure proper distancing in our encampments, ensure that proper hygiene is adhered to.”

The Centers for Disease Control website advises city governments not to clear encampments during the outbreak because “clearing encampments can cause people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers,” which could increase the risk of spreading the virus to others.

First-hand perspectives

The day the city announced it would stop sweeping encampments, activist and homeless resident Couper Orona said she received a phone call from friends telling her that police and Public Works employees had confiscated several tents and other belongings from an unhoused couple.

“I got there a little too late; all their stuff was on the truck,” she said, adding that she was told off by a police officer when she tried to retrieve the items on the owners’ behalf. “They took their tents, everything they owned.”

Christin Evans, a business owner and president of the Haight Ashbury Merchants Association, posted on Twitter pictures and video of a March 25 exchange she had with a police officer and Public Works employee after she witnessed the latter piling a tent and sleeping bag into the back of a Public Works truck.

“The person was not with their belongings and they took their tent,” Evans said, adding that she felt the worker did not leave enough time for the tent owner to return before loading the items into the truck. By comparison, she noted, “When I go to the bathroom, I take longer than that.”

In the video, Evans confronted the police officer to ask him why the things had been taken. The officer said he had asked nearby campers if they owned the items and they had said “no.” There was “no medication, nothing of value” in the pile of items, he said.

The Public Works employee told her “he was just doing his job,” she said. “It’s unconscionable,” Evans said, “particularly now.”

A ‘health and safety risk’ for the unhoused

Between March 16, the day the city ordered residents to shelter in place, and March 25, 144 encampments had been labeled “removed,” public 311 data show. According to the Office of the Controller, “removed” indicates that residents may have been offered services or an encampment may have been cleaned or moved along.

In addition to the phrase “Encampment removed,” notes written by city workers who responded to encampment complaints said that some tents were “taken down” or that encampments were “cleared from the sidewalk.” Others included the phrase, “Did not seize or enforce tent,” or that tent dwellers were given a COVID-19 information handout sheet and “educated and advised.”

On March 11, Public Works spokeswoman Rachel Gordon said the department would continue confiscating homeless people’s belongings during the coronavirus outbreak, a practice some activists expected would end when the city announced after several days that they would stop performing sweeps, though department representatives did not confirm this.

Public Works’ bag and tag policy allows for the confiscation of unattended items found during visits to homeless encampments, a practice that has long come under fire from activists who accuse workers of abusing the policy by throwing away or even stealing the items they find.

These policies may pose a “health and safety risk” for the city’s homeless population because they make it impossible for unhoused people to shelter in place, said the Public Works employee who shared the information about continued tent seizures.

“We don’t really want to do bag and tag right now either, but it doesn’t pose a safety risk to the workers so we can’t really fight it,” the worker wrote.

Advocates urge cities to stop seizing tents

Coalition on Homelessness organizer Kelley Cutler said that she too had heard of city workers taking belongings from unhoused people, though by her count, tent confiscations had grown rare. Instead, the police department had begun issuing move-along orders to homeless people from their cars, she said.

“We’re still not being told where people can actually be,” Cutler said. “We’re told where they can’t be.”

Homeless people are more vulnerable to diseases like coronavirus due to their propensity for underlying health conditions and lack of access to hygiene facilities, according to a report recently published by The National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. The report urges cities to place moratoriums on “sweeping encampments and seizing homeless people’s tents and other temporary structures.”

Public Works has not responded to multiple phone calls and emails since March 11. Representatives for the Human Services Agency, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, the Department of Emergency Management, the San Francisco Police Department and Jeff Kositsky also did not reply to requests for comment before this story was published.