For five years, since her doctor raped her at home, one woman in Los Angeles has had no luck getting “people search” sites such as MyLife and Spokeo to stop posting her address. Like many victims of rape, other violent crimes or harassing ex-spouses, she remains traumatized and fearful.

Although she has been circumspect about where she lives, these information brokers continue to post and sell her whereabouts and other details she considers personal and private.

“You don’t want a guy to go on the internet to look up where you live, and you try to protect your safety and you can’t, because you’re completely, easily Google-able,” said the woman, who lives alone and asked not to be identified. She just wants to vanish from the internet, a right that citizens of the European Union enjoy under the General Data Protection Regulation.

But even in the wake of last year’s passage of the California Consumer Privacy Act, the first of its kind in the United States, she and many others with reason to avoid public exposure will remain visible to the world. Though consumers may ask companies to delete or stop collecting data about them, the First Amendment and open-records statutes may thwart their efforts to get these information brokers to delete data after the law takes effect in January.

Personal Data That’s Quite Public

These businesses argue that the information comes from government entities, such as the state and municipal courts and motor vehicle agencies, and is publicly available.

“We actually don’t have an obligation to remove those records,” MyLife.com founder and CEO Jeff Tinsley said in an interview. The exception is for judges and law enforcement. Other removal requests, he said, are considered individually.

That may surprise Californians.

“Many people are under the misconception that there are laws that specifically protect them from having their personal information published online,” said Paul Stephens of the San Diego-based nonprofit Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. “For the most part, there are no such laws.”

‘Unconstitutional Speech Restrictions’

The Software and Information Industry Association, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing about 700 companies and organizations, argues that the state privacy law violates the U.S. First Amendment because it contains “unconstitutional speech restrictions.” In a memorandum filed with the California attorney general, the lobbying group said that the law restricts “the dissemination of accurate, publicly available information,” and that if not amended, “it is highly likely to be invalidated in court.”

The Legislature is considering adding language to exempt government records. The sponsor of A.B. 874, Assembly member Jacqui Irwin, a Democrat from Thousands Oaks, said she wanted to make sure the law did not impose “unconstitutional limitation on the use of public records, which the state and local governments make available to support transparency in government.”

Any limitation on what constitutes a public record must be scrutinized, said David Snyder, executive director of the San Rafael-based First Amendment Coalition. “I don’t think everything ought to be public, but I think you head down a dangerous road when you start saying, ‘Well, it’s a public record except in these circumstances.’”

Other privacy advocates agreed.

“Laws that protect consumer data privacy should be calibrated to not unduly burden free speech,” said Adam Schwartz, senior attorney at the San Francisco nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation.

New Law Silent on Emergency Requests

Though Californians will have expanded personal-data protections, information brokers will continue to sell and make available other facts about their lives, said Alastair Mactaggart, a businessman whose self-funded petition drive spurred legislators to propose and pass the new law.

That’s a big weakness, one professional data-scrubber said.

“Oftentimes individuals need to be removed from sites due to doxxing and/or direct threats to their physical harm,” said Will McAdam, founder and CEO of Los Angeles-based Privacy Duck, a fee-based service to remove people from information broker sites.

California’s privacy law has “no provisions for emergency removal demands and no provisions for emergency removal demands without having to turn over evidence such as police reports to private third-party people-search companies, creating more exposure,” McAdam said.

Loophole Over Selling or Displaying Data

He pointed out that there is no clear distinction between the “selling” of personal information and the “display” of it on dozens of sites. “This creates fine lines and loopholes for the people-search companies to take advantage of,” he said.

Federal law may need to be changed.

A starting point would be the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act, which allows the one-time sale of motorists’ information to private investigators or to any company claiming to update its records. State vehicle departments have been the main source of information for companies harvesting and selling people-search information, said McAdam, whose clients include public figures, activists and victims of crime, including identity theft.

New technology brings new forms of crimes, said Erica Johnstone, an attorney specializing in online harassment for Ridder, Costa & Johnstone in San Francisco. Sites listing family members and addresses can be used as “starter blocks” for ruthless cyberstalking campaigns, said Johnstone, who served on the Cyber Exploitation Task Force when U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris was California attorney general. She’s found harassment cases often extending beyond the targeted individual and spreading to family and friends.

Information Reposted After Opt-out Requests

Misinformation is another big problem.

“It’s important to remember that the information these companies compile can be incorrect, out of date or misleading, which may mean you lose opportunities just because someone does a simple search on your name,” said Meghan Land, executive director of Privacy Rights Clearinghouse.

Other privacy advocates pointed to the problem of information brokers reposting or “repopulating” data after being asked to take it down.

Rob Shavell, co-founder and CEO of a Massachusetts privacy firm called Abine, which offers the fee-based service DeleteMe, said “millions” of their opt-out requests showed that MyLife, Spokeo, PeopleFinders, Whitepages, PeekYou, Intelius and others frequently repost information several months after opt-outs.

MyLife Maintains ‘Suppression List’

He said his company, which works with the National Network to End Domestic Violence, has seen data brokers sell lists of abuse victims based on police reports. “Of course no company will admit it and you cannot audit them,” Shavell said.

Tinsley said that to comply with local laws, MyLife.com maintains a state-by-state “suppression list” of people to exclude. He denied that his site reposted data after opt-outs were received.

But McAdam and Shavell challenged Tinsley’s claims. McAdam said that in the past nine years he’s seen “tens of thousands” of Mylife.com profiles reappearing.

A Spokeo spokesperson said in an email that “we pride ourselves on providing one of the easiest opt-outs in the industry.”

“While we cannot comment specifically on CCPA given that the legislature is currently considering amendments, we agree with the spirit behind privacy laws like GDPR and CCPA regarding data transparency and control,” said the representative of the Pasadena-based company.

Background Reports and Reputation Scores

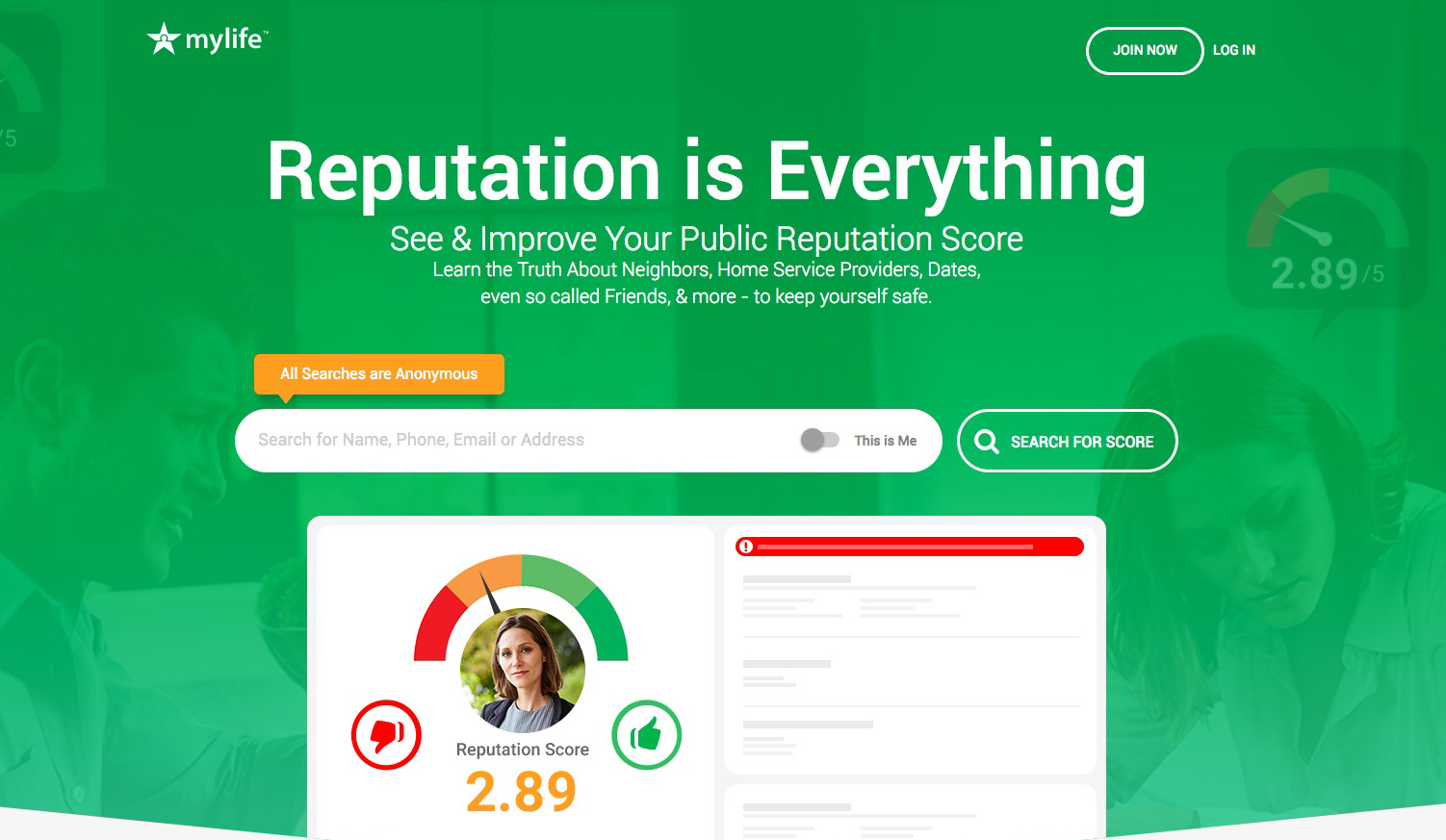

Tinsley launched his business in Los Angeles in 2002 as Reunion.com and later changed the name to MyLife.com. He said its mission is to make dating, home services or other marketplace sites safer and more trusted through background reports and reputation scores.

“What we actually do is we’re focused on helping making people feel safer,” he said.

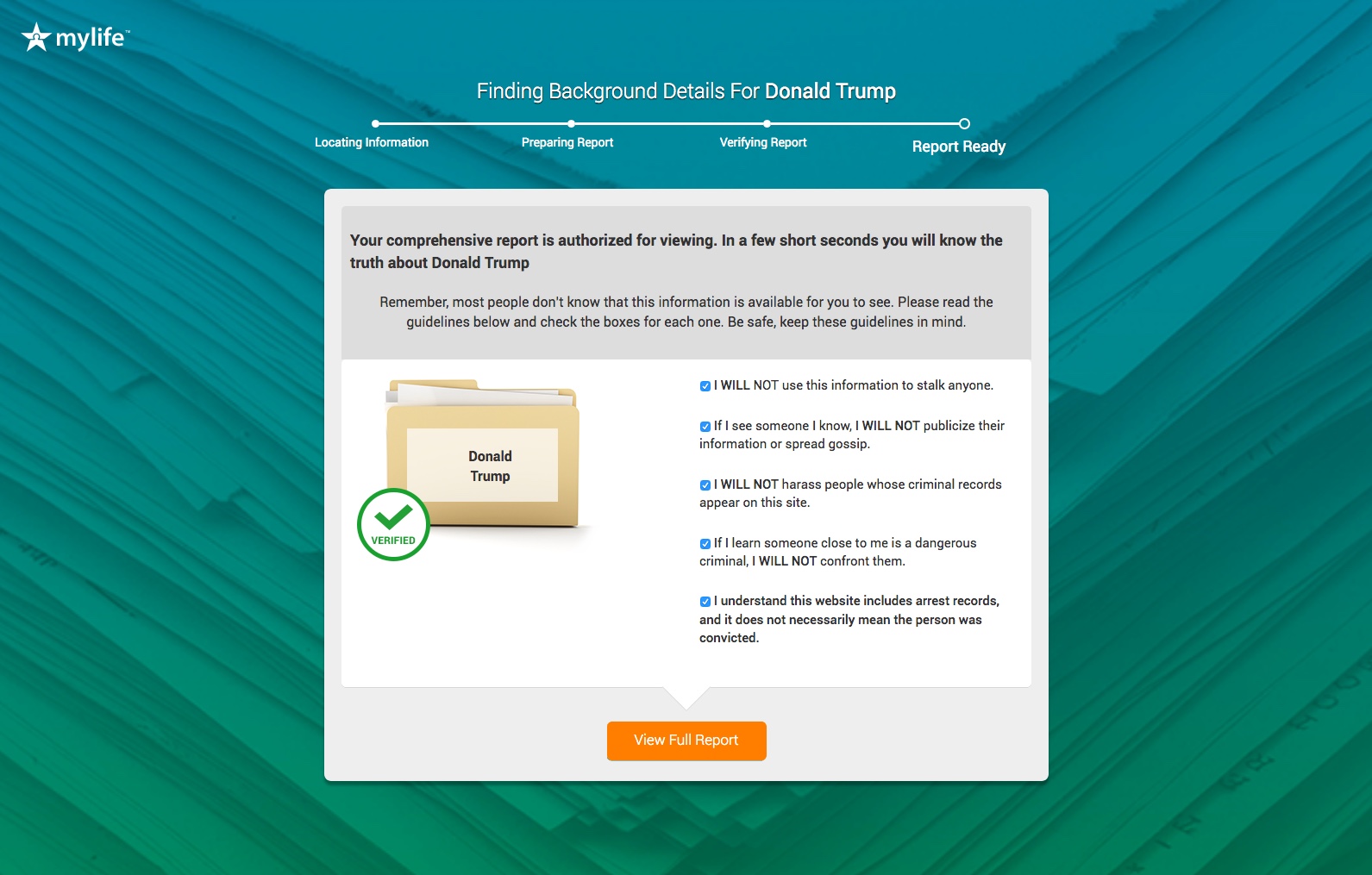

Privately held MyLife, which is not subject to detailed public disclosures about its business, culls information from state and municipal government sources nationwide that “make data available to others including groups like us,” Tinsley said. “We just pull it all together to make it easier for consumers.”

Information may include age, birthday, past and current home addresses, phone numbers, court records, traffic citations, email addresses, employers, education, photographs, relatives, political affiliations, a mini profile and a section for MyLife’s registered members to rate each other.

MyLife automatically generates a public page for everyone 18 years and older, and says it has more than 300 million such pages — a “complete Wikipedia-like biography on every American.” The Census Bureau estimated the total U.S. population on June 30 at more than 329 million. About a quarter were 18 or younger.

No Explanation For How Details Are Removed

Regardless of membership, these “public pages” cannot be deleted, MyLife’s policy states, adding, “Though if you have extenuating circumstances call our customer care department.”

Tinsley would not explain the guidelines for taking down information. He said victims of rape, domestic violence or other crimes did not have to produce police reports.

Tinsley could not explain how a rape victim’s information still appeared on MyLife.com. “I would need to see proof” that her file had been suppressed and later reposted, he said. “I don’t see how this would happen in our service.”

In a follow-up email he added that “there are a lot of features and benefits that are part of the premium membership which include the ability to have more controls over your Reputation Profile (think of it as a personal homepage that makes you look good) and the ability to help facilitate removal of your entries from other sites that you can’t control at all.” Monthly plans cost $9.95 to $15.95.

“The value of our services is validated by the public,” Tinsley said. “Over the past 12 months our MyLife and our services has been used by more than 160 million people, to learn about others and help manage the way they look online. Most members love our services.”

Complaints and Legal Troubles

The company’s public record shows a history of complaints and legal troubles with consumers and authorities, including allegations of inaccurate information, false claims and advertising, fraudulent credit-card charges and duping users into providing personal information. In 2015, the company paid a $1 million settlement to the City of Santa Monica and consumers for allegedly violating a California law regulating automatic subscription renewals.

The Better Business Bureau reports nearly 7,000 complaints about the company in the past 12 months and more than 10,000 over the past three years. Since 2016, Mylife.com’s rating has risen from F to B-, but it is not accredited by the business rater.

Though the new privacy law does not cover the removal of crime victim data, the California secretary of state’s “Safe at Home” program offers legal remedies for domestic violence, rape and stalking, said Tara Gallegos, a spokeswoman for California Attorney General Xavier Becerra.

If a home address and home phone number registered with the state program are not removed after a written request, the victim may file a lawsuit and request a court order, she said. Victims can complain to the attorney general or their local district attorney.

Stephens, of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, noted that people-search sites or information brokers can be sued for a “deceptive practice” if their privacy policies state they will remove information upon request but do not.

That’s little comfort to the woman from Los Angeles, who said she feels that MyLife and its competitors are victimizing her again.

“All the info sites suck,” she said. “I want to be unknown and be able to fade away. The world we live in today does not allow this. I spend my life constantly combatting it and removing myself. That’s my fight.”

Reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.