This article is adapted from an episode of our podcast “Civic.” Click the audio player below to hear the full story.

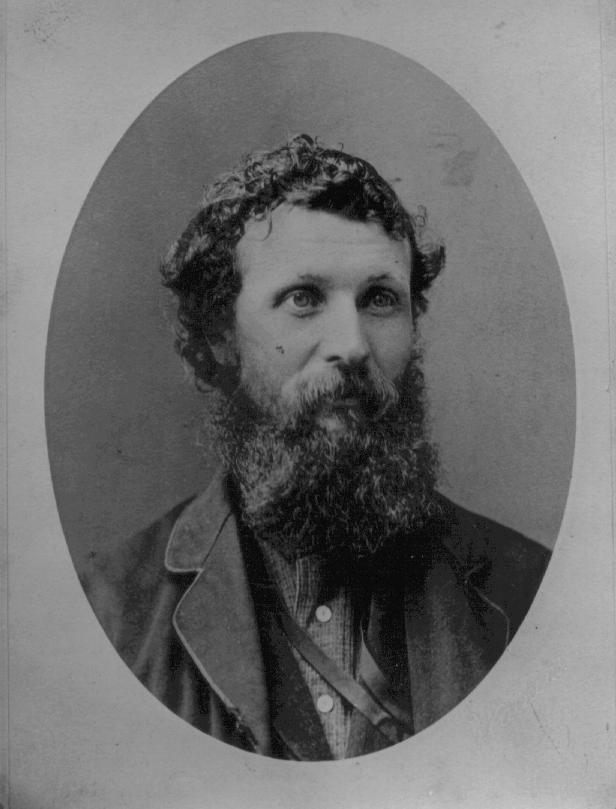

The racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer inspired the reexamination of many historical figures, including John Muir, the man often called “the father of the national parks.”

Even the Sierra Club, which Muir founded, issued a statement in June 2020 acknowledging some racist language in his early writings. It read, in part: “Muir was not immune to the racism peddled by many in the early conservation movement. He made derogatory comments about Black people and Indigenous peoples that drew on deeply harmful racist stereotypes, though his views evolved later in his life.”

Muir has been honored extensively, with his name on many sites and institutions, including 28 schools, a college, a number of mountains, several trails, a glacier, a forest, a beach, a medical center, a highway and Muir Woods National Monument, one of the most visited destinations in the Bay Area. But in the time since the Sierra Club issued its nuanced statement, some have come to believe that Muir’s legacy should be diminished because of his racist statements, despite his contributions to the preservation of wilderness and later writings praising native tribes.

John Muir is such a touchstone and cultural icon for Californians that “Civic” decided to take a look again at his legacy by traveling to Yosemite National Park in Mariposa County.

Choosing which stories to tell

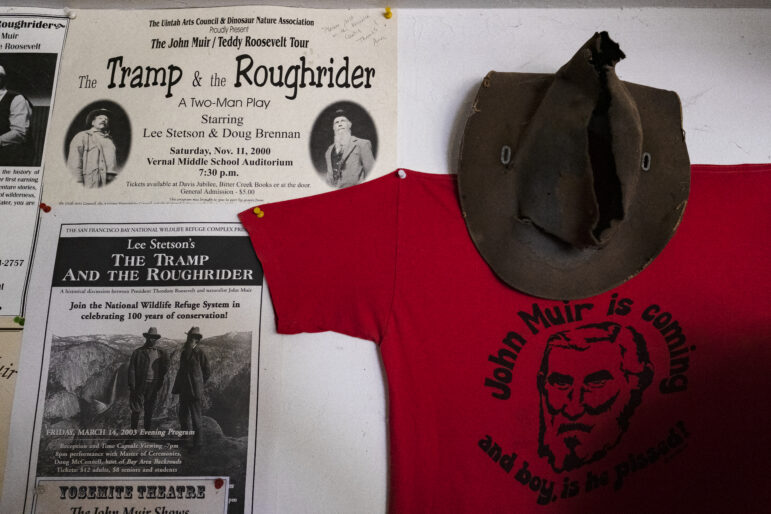

Lee Stetson has studied John Muir and performed as Muir in six one-man shows he wrote about the 19th- and early 20th-century naturalist. Stetson has thought long and hard about Muir’s legacy and the disparaging statements he made about impoverished people he encountered in his early journeys.

“Context is the question,” Stetson said. “We have to consider the comments from a young man who was first encountering the Black people in the South as he walked down to the Florida keys from Kentucky.” Muir’s comments on the Indian cultures that he met related to what Stetson called the “shattered cultures,” or tribes decimated by displacement.

Muir called the handful of Miwuk living in Yosemite who had survived a racial genocide “dirty.” But his later writings show that his attitude shifted over time.

“When he arrived in Alaska” in 1899, Stetson said, “he was accompanied by and guided by Indians. He became incredibly fond of them. He was engaged with Indian cultures that were fully intact. His understanding of their loyalties, their families, their culture in general, was certainly very positive in every way.”

Regardless of whether one agrees with the argument for putting John Muir in historical context, when it comes to national parks, we often forget the people for the trees. But some of the Miwuk — people who still call Yosemite and the land surrounding it home — say the credit given to Muir for his stewardship and preservation efforts are overstated.

“We were the first stewards of the land to be there,” said Sandra Roan Chapman, chairperson of the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation. “They say John Muir found Eden. He didn’t find Eden. It was always there.”

“Everything you read about in Yosemite is about John Muir,” she said, adding that members of other tribes have told her they feel the way she does, wondering why Muir’s name is on so many sites that are significant to Indigenous people. “Why do we always have to have John Muir on our sites? So, to me, it’s like, if it wasn’t him, it would have been somebody else.”

She said that when Muir entered Yosemite, he knew nothing about the impoverished people in the region who survived by working for mostly white tourists.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Sandra Roan Chapman, chairperson of the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, says her tribe is fighting for federal recognition and other initiatives to keep their culture alive. “They banished us out of Yosemite, but we’re still here,” she said.One might argue that debating John Muir’s legacy centers the focus on one man, rather than sharing the history of displacement, violence and inequity faced by native tribes.

The members of the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation have more pressing things to contemplate than John Muir’s legacy. They are fighting for federal recognition, acquiring resources for their community and keeping their culture alive. They recently reached an agreement with the National Park Service giving them control of the site of a former native village in Yosemite Valley that was demolished by the park service in the 1960s. Construction on the site is under way to give the tribes a cultural and educational center in the heart of Yosemite. (The Public Press will share stories about those developments in future reporting.)

Rather than dwell on the negative things Muir said, Chapman said she prefers to focus on the possibilities for her tribe and others.

“They banished us out of Yosemite, but we’re still here,” she said. “And because we have our laughter, and we have our ceremonies, and we stay positive with everything that we’ve gone through, all the hardships and everything that we’ve had, we still stay positive. And that’s what you have to do.”

Fighting for nature

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

John Muir wrote extensively against damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley: “These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and, instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar. Dam Hetch Hetchy!”San Francisco prides itself on being green, but much of those bragging rights come from the clean hydro power from the O’Shaughnessy Dam at the mouth of Hetch Hetchy Valley. Since the completion of the system carrying water from Yosemite in the early 1930s, it has given San Franciscans pristine water to drink and with which to flush their toilets.

Muir spent the later years of his life fighting the construction of the dam, taking a major role in a national campaign to defeat the project. Despite his efforts, the trees in the valley were cut for lumber and the sacred sites of the Miwuk were drowned when dam construction began in 1916.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Actor and scholar Lee Stetson displays memorabilia at his home near Yosemite Valley from plays he wrote and in which he portrayed John Muir. Stetson began his career in acting in Los Angeles before catching his first glimpse of Yosemite Valley in 1982 from the Columbia Point overlook. “I was so smitten by the view of it,” he said.In addition to his work as an actor and playwright, Stetson served on the Mariposa County Board of Supervisors from 2011 to 2015 and has strong feelings about the lost valley.

“To drown it to a depth of 400 feet was to essentially obliterate a great national treasure,” he said. “They could very easily have stored that water downstream. We could do that today. There would be some loss of electrical power that is currently generated, but that can be replaced.”

Stetson is a supporter of the Restore Hetch Hetchy movement that wants to remove the dam and store the water downstream.

“You could easily blow a hole in it — most of that sand would pour out that has built up at the bottom of it,” Stetson said.

“In a few generations, we could have that valley back to us to a significant degree,” he said. “It would have a bathtub ring around it for a number of centuries. But hey, the planet can handle a couple of centuries.”

Echoing Muir

In our interview with Stetson, we had him take on the role of Muir, something he has done in his plays and at live events the world over, using his deep knowledge of the man’s writings and experiences.

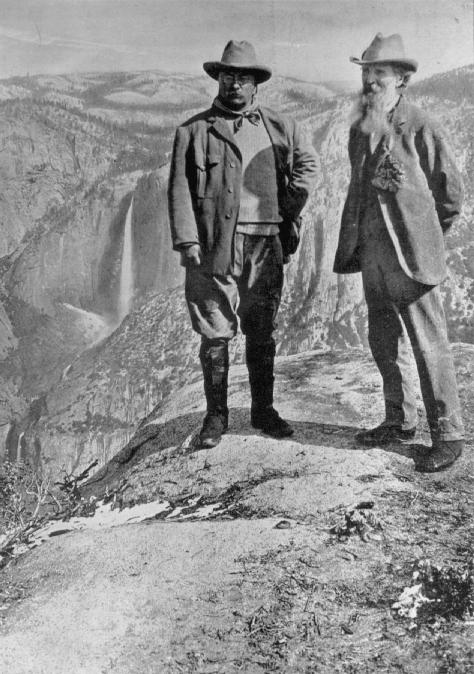

In the most important political moment of his life, John Muir convinced President Teddy Roosevelt to spend three days camping with him in Yosemite in May of 1903. Muir influenced the nature-loving president to expand Yosemite and create more national parks and monuments, setting a significant precedent for land conservation.

I asked Stetson, speaking as Muir, where he would take political leaders today.

“The Hetch Hetchy Reservoir,” he said. “I think one could find a great deal of instruction in it. And then, take them to Yosemite Valley and to show them what the Hetch Hetchy could look like. To preserve it is to preserve the loving process of creation. It is an enormously important thing to be doing.”

Stetson as Muir answered our final question: What would you tell the average person about why we still need wilderness?

“To go to it,” he said. “Go, because everybody needs to be kind, at least to themselves. And go because everybody needs beauty as well as bread, in places to pray and then play, where nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.