When Nobody moved into a tent in the sanctioned encampment on Stanyan and Haight streets in the spring of 2020, staff quickly gave him a nickname. As the front desk staff signed him in and out of the site, his chosen street name was lovingly replaced by “Somebody.”

It didn’t stick, but he appreciated the sentiment. Now at a different sanctioned camp, Nobody isn’t even called by his name. As he comes and goes from a south of Market parking lot, he is instructed to recite the number of the painted square of asphalt where he pitches his tent.

“I’m not Nobody,” he said. “To the staff, I’m just B2.”

The site in an old McDonald’s parking lot at the edge of Golden Gate Park opened in May 2020 with 40 spots, becoming the city’s second sanctioned tent camp. It quickly made headlines as neighbors and business owners sued the city in an attempt to prevent it from opening. On June 16 it shuts down ahead of plans to develop the lot into affordable housing.

The question now is where to move site residents, many of whom have called the Haight neighborhood home for decades and don’t want to leave. The Haight has no shelters or navigation centers. Vacant housing units are limited as well, with 75% earmarked for people living in what have become known as shelter-in-place hotels, where rooms were repurposed for housing people who had been living on the streets during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, residents of the site, operated by the Haight-based nonprofit Homeless Youth Alliance, are being relocated to temporary shelters in other neighborhoods. (Full disclosure: reporter Nuala Bishari worked at the site part time as a front gate check-in worker from June to October 2020.)

Young people experiencing homelessness have always been drawn to the Haight, in large part due to its tight community on the street, said Mary Howe, executive director of the Alliance. “People exiting traumatic relationships, events and family experiences want to live in a community, not in isolation,” she said.

Interviews with residents and results from Alliance surveys suggest many felt a strong sense of community at the site. “It’s the first home I’ve had in 20 years,” said a longtime Haight resident who goes by the street name Booze.

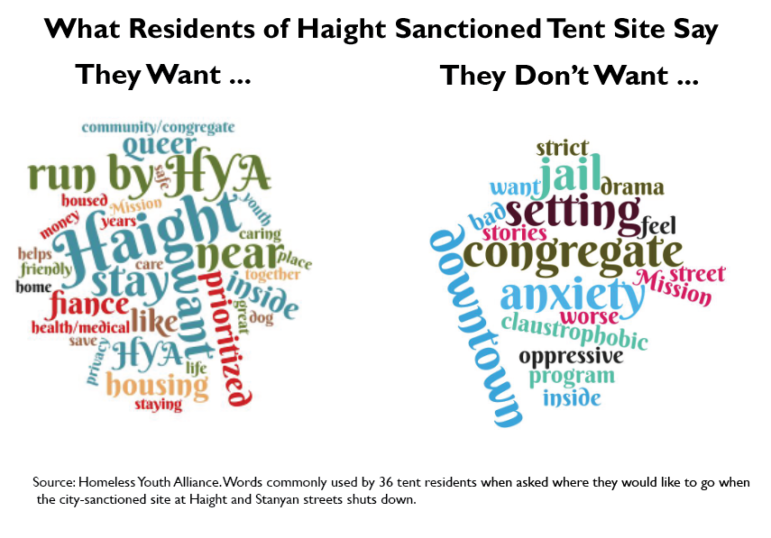

In April, with the site’s closure date looming, staff conducted a poll of where residents would like to go.

Respondents’ top choice was permanent supportive housing, with shelter-in-place hotels coming in a close second. A few said they would return to the streets; only one expressed desire for another sanctioned tent site as a first choice. Nearly everyone said they would take anything, as long as it was in the Haight.

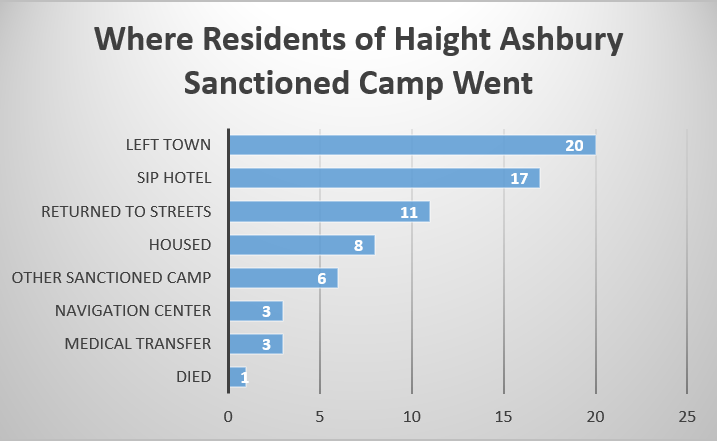

Of the 84 people who stayed at the site over the last year, 69 have moved on. One died from a suspected overdose. A substantial number either left San Francisco or were relocated to hotel rooms.

The transition out of CAMP and away from the Haight hasn’t been easy.

“I’m isolated from my community,” said Ashel, a former resident of the Stanyan site who was moved into a shelter-in-place motel in the Marina district a few weeks ago. “This is as close as the city could get some of us to Haight Street. But we’re not even allowed to go to each other’s rooms to say hi.”

Frequently, the young people the Alliance serves deteriorate when they are moved out of the neighborhood and their community, said Howe. “Often their mental health decreases, and things like drug and alcohol use increase as a coping mechanism in response to the dramatic shift of environment,” she said.

Launching the sanctioned tent site

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit San Francisco, homeless service providers scrambled to modify their programming, balancing the need of continuing services with keeping people safe. As word started spreading about sanctioned tent encampments, Homeless Youth Alliance — which has provided case management, housing referrals and syringe services to the Haight for decades — turned to the people it serves to gauge their interest.

Howe drafted a simple ranked-choice survey administered in April 2020 to assess whether and where people would like to move. Of 50 people polled, 41 marked a hotel room as their first option. With 35 votes, a sanctioned campsite came in as a close second.

Outreach started weeks before the site — christened Community Action Made 4 People, or CAMP — was ready for residents. Staff visited three large neighborhood encampments almost daily, building trust and making a list of people who would relocate.

“By the time we opened, we knew everyone,” site manager Eliza Wheeler said. “We had this running list of people who were like ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ and ‘maybe, I’ll see what my friends say’. Sometimes it was as easy as saying ‘we’re going to have showers’ and they’d say ‘sign me up’.”

The sanctioned campsite opened May 19. Within two weeks it was full.

How a parking lot became a space to call home

Despite high winds that repeatedly destroyed tents, wildfire smoke that choked the city for weeks, raccoons and sewer grates that overflowed when it rained, most of the residents have only good things to say about their year in the old McDonald’s parking lot.

One of the first arrivals was Nobody, who had been living in a Masonic Street encampment. With two fractured ribs and a collapsed lung, he was having a hard time living on the street.

“Going in here was a lot easier to recuperate than being on the ground,” he said. “They got me an air mattress, and a tent, and a light, and a solar-powered battery bank.”

From the get-go, Homeless Youth Alliance worked to create a space that felt like a home. Weekly meetings offered residents a space to vent and support one another. Multiple community tents, from a cobbled-together kitchen to a TV room to an art space, provided space to socialize.

“This was an opportunity to get stable enough and feel safe enough to have a conversation about being ready for something else, to move forward,” Wheeler said.

A future unknown

Fourteen residents remained at the site as of June 4. Several who medically qualify will move into shelter-in-place hotels; others are going to other sanctioned encampments. A couple are leaving town. But with two weeks to go until the site closes for good, seven people said they did not yet have a plan.

“The process of closing and witnessing people scattered throughout the city as the community they’ve built here comes to a close has been heartbreaking,” said Wheeler. “However, I hope they will take this experience with them and be stronger and fiercer advocates for how they want to live, and where.”

For those who have moved on from the parking lot, there’s still a lot of uncertainty. Ashel, who secured a room in a shelter-in-place hotel, said they would return to the Haight if a new sanctioned campsite opened. Ashel uses gender-neutral pronouns.

“I think they should find out what’s happening at Kezar parking lot, and put CAMP right there in the park,” they said. “I’m not willing to take any housing options they give me at this point, because I don’t want to be in the Tenderloin.”

Nobody does not like sleeping at his second sanctioned tent camp but did not qualify when he applied for housing.

When asked where he would go when his new site shut down, he paused for a few moments. “I didn’t even think about that,” he said. “I’ll probably take my tent and move to the beach. Better than being in the park and getting attacked by coyotes and raccoons.”