This article is adapted from an episode of our podcast “Civic.” It is the second in a two-part series examining factors contributing to recent increases in drug overdoses in San Francisco and ways to mitigate the problem. Click the audio player below to hear the full story.

The key to addressing San Francisco’s overdose crisis, say community activists and medical experts in the city, is harm reduction.

That’s an approach that acknowledges not all drug users will achieve abstinence, and that focuses on keeping them safe and alive if they are not ready or able to quit. Drug overdoses killed more people in San Francisco than did COVID-19 in the first two years of the pandemic — 711 deaths in 2020, and 645 in 2021.

Laura Guzman, a senior director at the National Harm Reduction Coalition, described the approach as “a social justice movement” that got its start during the AIDS crisis. The movement focused on practical solutions such as syringe exchange, she said, while also developing strategies and principles that minimize the harms caused by drug laws targeting Black, brown and indigenous communities.

“Reducing harm means also to undo the stigma, and to undo the incredible impacts of a violent system that is not just policing and incarceration of people who use drugs, but also systems that really neglect the overall health of people who use drugs,” she said.

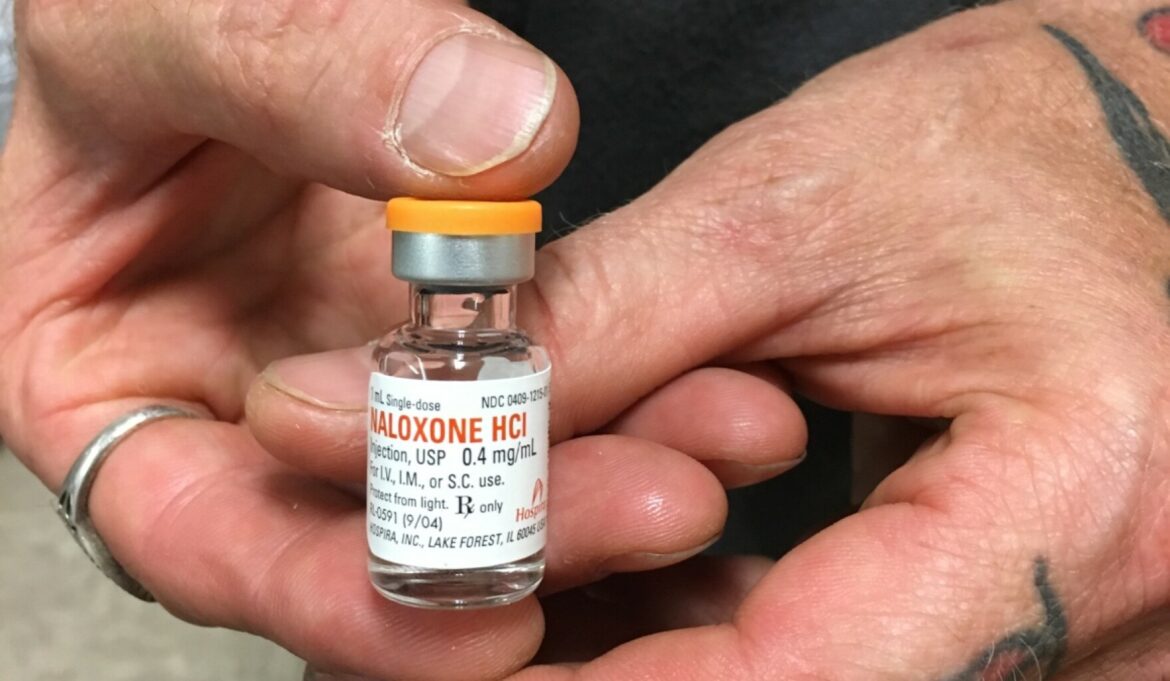

Offering clean needles and distributing naloxone — a drug that can stop an opioid overdose — to drug users are first steps.

Programs to get naloxone into the hands of people who can help stop overdoses have been around for decades. Eliza Wheeler works with the Remedy Alliance/For the People, which gives harm reduction programs across the country access to naloxone. The top priority for naloxone distribution is people who use drugs.

“People who are potentially at risk of overdosing are often around other friends or other people who are using drugs,” Wheeler said. “And those people are in the most important and crucial position to reverse those overdoses, especially in a time-limited situation where it’s not always possible to get first responders to come.”

Some wonder why naloxone isn’t distributed more broadly. Wheeler said the challenge is that supply-chain issues in manufacturing are common, pointing to a production delay that occurred last April at a Pfizer plant.

“This happens quite frequently in pharma manufacturing,” she said. “The manufacturing of generic injectables is one of the most highly regulated and it has to be extremely safe.”

Wheeler’s organization has an arrangement to acquire the drug through a buyers’ club that distributes to 120 harm reduction programs operating in 39 states and the District of Columbia. The club purchased 1.3 million doses in 2020.

While Wheeler prefers that harm reduction service programs distribute naloxone resources to drug users, she is not opposed to other people acquiring and carrying naloxone, and learning how to use it.

“You can get nasal naloxone from pharmacies,” she said, adding that it can be acquired without a prescription. “And I would strongly recommend everyone carrying it.”

A concerned bystander who believes they’ve encountered someone experiencing an overdose should call 911, Wheeler said, and then help get the person sitting up or laying on their side to increase airflow.

In the short term, an overdose requires emergency response. In the long term, people who have used drugs and experienced overdoses might choose to seek treatment.

Dr. Dan Ciccarone, a clinician and a professor at the department of family and community medicine at the University of San Francisco, California, Medical Center, who researches the public health aspects of drug use, said treatment for opioid use disorder can take many forms.

“If we recognize that opiate use disorder is a brain disease, and we through clinical experimentation, find treatments that work for that, then we’re working on a disease model. We’re working on a biological medical model of disease,” he said. “The good news is that we have medications that work. We have treatments for opiate use disorder.”

Three proven medications are buprenorphine, methadone and an extended-release form of naltrexone.

Methadone is highly effective but can only be used in methadone clinics, which are highly regulated.

Buprenorphine can be prescribed by anyone with a prescribing license, and Ciccarone said that he and other addiction medicine professionals would like to see regulations reduced so that it could be prescribed as easily as insulin is for diabetes. That would mean many more medical professionals would be authorized to help those who need treatment.

San Francisco is recognized for having a robust treatment system, but not everyone with opioid use disorder gets treatment, said Dr. Hillary Kunins, director of behavioral health treatment in San Francisco’s Department of Public Health.

“We have some of the most effective forms of treatment for opioid use disorder, in particular for opioid addiction, available, and that most effective treatment scientifically is treatment that includes the use of a medication,” she said. “Nonetheless, not everyone takes advantage of getting that treatment for many different reasons. One is part of the disease of addiction is somebody might not be ready for treatment, feels ambivalent about their use, or experienced the drugs sort of as being part of their life, that it’s hard to give up.”

While treatment may involve going through detox, Kunins said that is not enough.

“Without ongoing medication support, that strategy, a person will have a very, very high rate of returning to drug use — more than 80%,” she said. “It is simply not effective.”

And for those who go through detox, not taking maintenance medication can put them at higher risk for overdose if they use opioids again.

“When a person has stopped using all opioids, their body becomes what’s called naive to the substance,” Kunins said, noting that makes them extremely vulnerable to overdose. Taking methadone or buprenorphine, she added, “decreases risk of overdose, protects them from a relapse and improves their health outcomes, including mortality.”

Outpatient treatment with methadone or buprenorphine might last months or even a few years. While a residential treatment facility offers a more comprehensive approach — perhaps including counseling, assistance getting housing and employment or vocational training — the use of medication leads to the best outcomes, Kunins said.

Rehab treatment quality, philosophies and cost vary dramatically. Tracy Helton Mitchell, an addiction specialist and author of “The Big Fix: Hope After Heroin,” said rehab programs need more regulation.

“There is no set agreement in the United States, what a rehab is supposed to be, what the outcomes are supposed to be, what is the treatments they’re supposed to be providing,” she said.

“A lot of these rehabs are based around abstinence-based ideologies where they don’t want to let people on these medications come into their facilities,” Mitchell said, referring to maintenance medications. “So, the United States is in a great state of upheaval now, because you have so many people wanting to get into rehabs.” She pointed to an insufficient number of beds and disagreements about treatment protocols as major obstacles to providing adequate help.

Guzman of the National Harm Reduction Coalition reinforced the idea that treatment involves more than just an abstinence-based approach.

“A lot of people equate ‘works’ with treatment, recovery and being 100% clean, and that does not work for everybody,” she said.

“The goal is to get our folks to be treated with dignity and respect,” Guzman said. “And also, to allow them to shine, whether they use drugs or not.”

This way of thinking is gaining traction in San Francisco. Groups like Code Tenderloin and other community organizations are partnering with medical institutions such as UCSF, and incorporating expertise from people who have worked in clinics and those who have experience with drug use. San Francisco’s Department of Public Health is also taking a multifaceted approach to the overdose crisis, said Kunins.

“Lots of folks are not in that moment ready to agree to stop using or even to reduce their use of drugs,” she said. “And so how do we help them in the moment?”

Broad support for harm reduction practices represents a significant shift in both local and national policies.

For years, cities tried “arresting our way out of the problem,” Kunins said. “The hope and theory was, if we could stop drug sales, we would reduce the number of people addicted to drugs, and we would reduce the consequences of people being addicted to drugs.”

While there may still be a need for public safety interventions, she said, “what we have learned is having health approaches at the center of our solutions, and often in the lead part of the solutions, is critical to successes that we’ve seen both historically and now.”

Ciccarone said he is hopeful that harm reduction will finally become a pillar of federal drug policy.

“One does not see much evidence to support the billions upon billions upon billions of dollars that we’ve spent in reducing drug supply,” he said. “Maybe what we’ve been doing has been keeping it from getting much worse, but reduce criminal penalties, reduce levels of incarceration, because that’s clearly not helping — it only helps people become more dysfunctional in their life as opposed to healthier.”

“For the first time in American drug policy history, harm reduction is going to be a pillar of the 2022 National Drug Control Policy,” he said. “I’m proud to say that I was a key figure in making that happen. It’s going to be sort of the capstone of my career, is reorienting American drug policy toward harm reduction,” which treats people where they are, destigmatizes their circumstances and works on principles of equity and fairness.

“Because it’s inclusive, because it’s inviting and a trust-building. It engages people, and it’s the one missing piece in the problem here,” Ciccarone said. “If people are running and hiding because they’re afraid of being judged, they don’t come to your clinic. They don’t come to your treatment program.

“Harm reductionists have been engaging them for 20 years now. And it’s about time we support the harm reductionists and the harm reduction community to continue that work.”

Use the player at the top of this story to listen to the full episode for an extended conversation on these topics and others related to overdoses. For Part I of this series, see: “Surge in Overdose Deaths Is a Puzzle Public Health Experts Are Desperate to Solve”