This special report appeared in the Spring 2012 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press.

A California group dedicated to stopping human trafficking is hoping to take its fight directly to voters this fall.

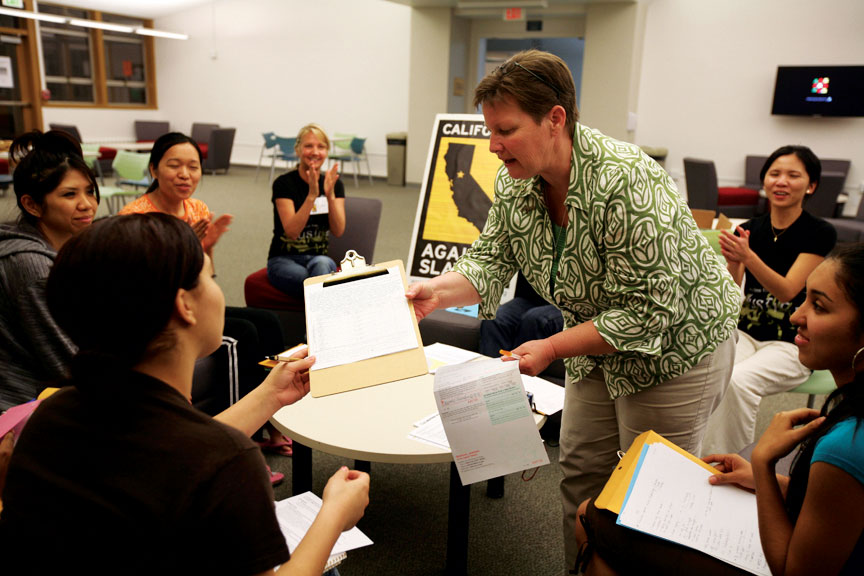

In January, the nonprofit advocacy group California Against Slavery began circulating petitions to get a measure on the November 2012 ballot to strengthen the state’s human trafficking laws. The measure is called the Californians Against Sexual Exploitation Act, and the campaign has mobilized hundreds of people around the state to collect the 800,000 valid signatures required for the measure to make the ballot.

Among the harsher penalties on traffickers and provisions to protect victims, the act would:

- Increase criminal penalties on human traffickers, require them to register as sex offenders and make them report private Internet access to law enforcement

- Use criminal fines to support victim services

- Require all police to undergo at least two hours of training on trafficking and how to treat victims

- Prohibit evidence of a victim’s past sexual history from being used in a trafficker’s trial

In 2009, Daphne Phung first learned about human trafficking in the United States from a TV documentary.

“I was shocked by the lack of justice,” said Phung, who went on to found California Against Slavery. “We first circulated the petition two years ago, when the organization started, but couldn’t get all the signatures in five months.”

The initiative is a joint effort. Authors include Sharmin Bock, who spent 23 years as a prosecutor in Alameda County, which the FBI has identified as a hotbed of domestic human trafficking. Chris Kelly, chief privacy officer and head of global public policy for Facebook, wrote the proposed law’s digital penalty. The Polaris Project, another anti-trafficking organization, reviewed the petition as well. Phung said more than 1,000 volunteers from across California have contributed to the campaign.

The effort to put this measure on the ballot has some skeptics.

“One gentleman told me the CASE Act wouldn’t pass — voters wouldn’t continue overcrowding prisons,” said Robert Joeger, a filmmaker from Orange County who volunteered his time creating videos for the organization. “But it’s not just going to be funded by tax dollars.”

Some question the statistics the group has used to promote the cause. Much of the initiative was formed on the recommendations of a 2006 study that Phung now acknowledges was outdated. Last June The Village Voice in New York criticized the methodology used to gather the statistics.

But backers of the initiative say they cannot wait for perfect studies.

“Trafficking victims don’t raise their hand,” said Sandra Morgan, director of the Global Center for Women and Justice at Vanguard University, a Christian liberal arts college in Orange County. “No one with experience in this will give a flat number.” Morgan is also founder of Live2Free, a youth initiative against slavery and the former administrator of the Orange County Human Trafficking Task Force, so she has seen many cases that don’t get officially counted.

“Some crimes related to human trafficking never show up in the statistics,” she said. “For example, it might have been prosecuted as a gang case.”

Morgan said more awareness is needed about labor trafficking and exploitation. “We find what we are looking for,” she said. “Sometimes immigrants fall through the cracks.”

Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O’Malley is worried about the scope and implementation of the new voter initiative.

“I’m leery of laws that come to us through initiative process,” O’Malley said, noting that once they are passed they are difficult to amend if found later to be flawed. “You can’t change the initiative.”

Others in the legal system don’t share her concerns.

“I’m not political, but anything that can help us fight against human trafficking is a step in the right direction,” said Holly Joshi, head of the Oakland Public Defender’s Office vice and child exploitation unit, which has five officers.

“We are struggling,” Joshi said. “It’s the second-fastest-growing crime in the country. This crime has really gotten ahead of us. It has reached epidemic proportions.”

Law enforcement, service professionals in the field and activists said deep budget cuts have hampered their efforts. Joshi’s unit has no safe place for victims to stay, except for juvenile hall. She told of a young, domestically trafficked girl who was released from custody in 2008 to return to her family. The girl returned to her pimp, who killed her.

Trafficking victims talk of negative experiences and a culture of distrust between them and law enforcement.

Leah Albright-Byrd recalled her arrest at age 15, when she was already a victim of human trafficking. She described the tight clasp of handcuffs and how the police officer said she “looked like a hooker.”

“I was treated like a criminal,” Albright-Byrd said. Had that officer known what kinds of questions to ask, Albright-Byrd might not have remained a victim of human trafficking for three more years after that arrest.

When she was 14 a pimp convinced her that abuse and exploitation would be inevitable parts of her life. He told her that she “might as well get paid for it.” She recounted how he used words like “love” and “protection” as weapons.

Today, Albright-Byrd is executive director of Bridget’s Dream, a nonprofit dedicated to advocacy, prevention and victim services. She works with California Against Slavery as a speaker and educator.

Phung acknowledges that the two-hour police training the initiative requires would not by itself form bonds of trust with victims. “This is only the beginning of awareness,” Phung said.

Yet offering more training for law enforcement had dramatic results in Orange County, said Live2Free founder Morgan.

“They start to see cases that were there all along,” she said. “Now they are able to recognize and prosecute them.”