On the ground in Shanghai with the men who are tackling, weld by complicated weld, the largest public works project in Bay Area history//

When all the pieces are finally welded together and tethered by the main suspension cable, the Bay Bridge east span will be not just a new American icon, but also a truly global monument.

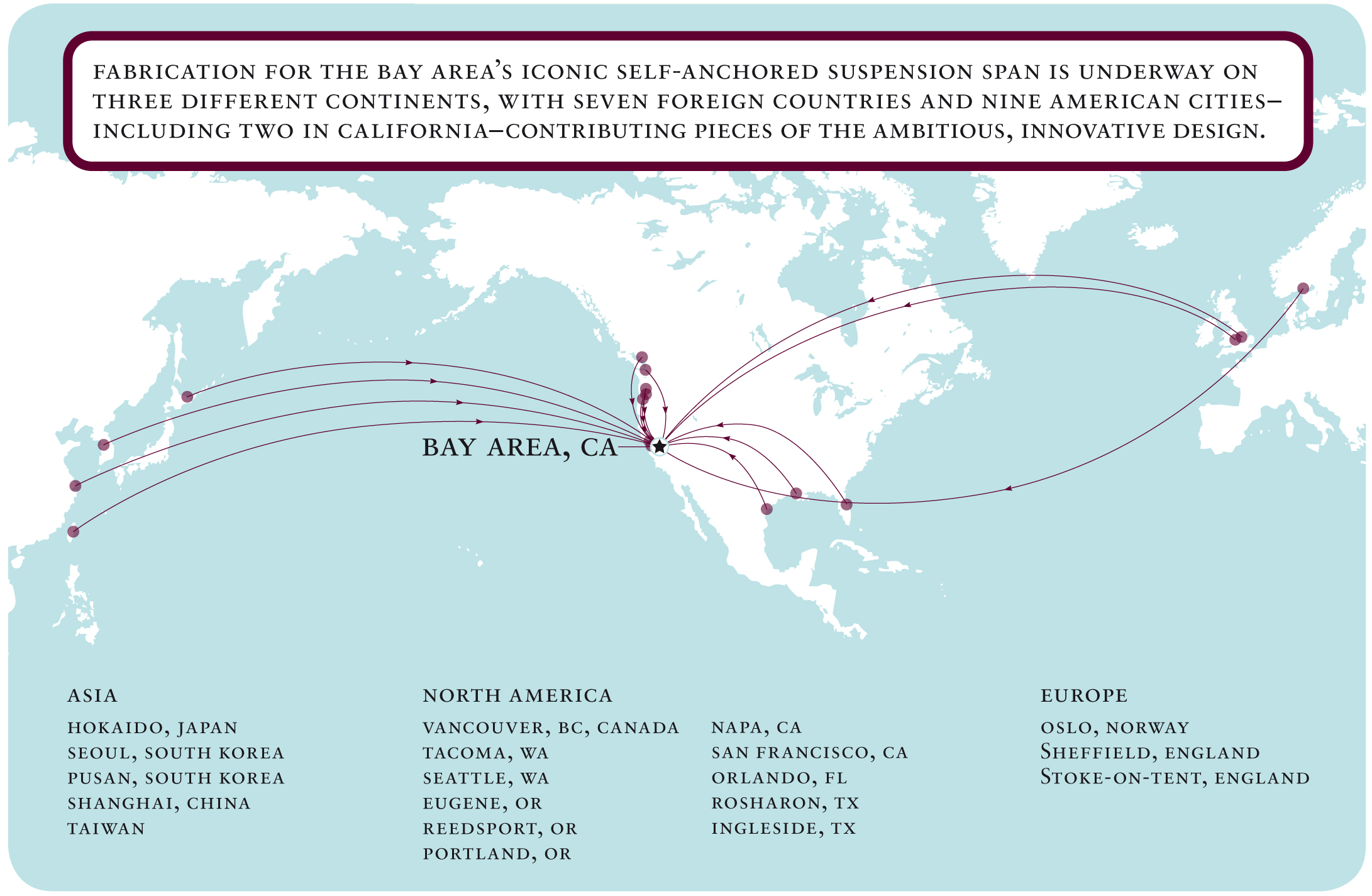

From the enormous solid steel castings of cable saddles, brackets and bands being forged in Japan and England to the gigantic bearings and hinges being manufactured in South Korea and Pennsylvania, fabrication of the bridge is under way in seven foreign countries and in more than two dozen American

cities, including 12 in California.

CHIP IN FOR THIS REPORT ON SPOT.US |

No foreign country is contributing more in terms of labor and critical components than the People’s Republic of China, where Shanghai’s Zhenhua Port Machinery Co. (ZPMC) is fabricating the heart and soul of the new Bay Bridge.

A subsidiary of China Communications Construction Co. Ltd, a major international infrastructure design and construction firm partially owned by the Chinese government, ZPMC is relatively new to the bridge-building industry but has a prolific history of producing immense steel structures.

Best known for its dominant global role in producing container cranes, such as the bevy of dinosaur-like structures grazing in the Port of Oakland, ZPMC is poised to expand its share of global steel production if it can deliver on Caltrans’ demanding expectations for the east span.

In April 2006, when Caltrans awarded the contract for the most complex and ambitious part of the east span replacement to the lowest bidder, American Bridge/Fluor (ABF), it was the inclusion of ZPMC that provided a critical price advantage: Chinese steel and labor was $400 million cheaper than it was for domestic steel fabrication.

ZPMC had its manufacturing capabilities in place, eliminating the need for expensive and time-consuming construction of a domestic fabrication facility. American Bridge’s working relationship with the company was established when ZPMC provided steel deck plates for the new Carquinez Bridge that opened in 2003.

Sprawling across more than two square miles along the southern shore of the city-size Changxing Island, in the mouth of the Yangtze River Delta, the ZPMC facility is the largest of its kind in the world. The fabrication yards set aside for the Bay Bridge project are just a patch in the quilt of warehouses where 20,000 people work, forging 80 percent of the world’s container cranes and other gargantuan steel structures, including the 67,000 tons of steel destined for the east span decks and tower legs.

Seventy years ago, when American Bridge engineered the Bay Bridge structure being replaced today, ironworkers slung hot metal rivets from buckets as they fastened steel plates together hundreds of feet in the air.

Today, the components are manufactured in huge yards and then shipped on a month-long journey across the Pacific before being lifted into place with the largest floating crane on the West Coast, named the “Left Coast Lifter”—also built by ZPMC.

“Life at the factory level is a tough one,” said Tom Paiva, a Los Angeles–based photographer hired by MTC to document the construction in Shanghai. Workers put in 12-hour shifts, six days a week, Paiva said, keeping operations going 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Paiva sought to capture the spirit of the struggle and patriotism permeating every aspect of worker life at the Changxing Island plant. He snapped his shots in the late-night hours when the juxtaposition of darkness and the welding sparks were at their greatest contrast.

//“The simple fact is, despite the fact that we got a bid for domestic steel, I’m not sure that there is a domestic steel fabricator that could do what ZPMC is doing” in terms of scale and their capability for the “massivity of this project,” said MTC executive director Steve Heminger.//

Splitting his time between fabricators for the steel components of the bridge deck and tower and the manufacturer of the main cable, Paiva provided a photographic window into the soul of the project.

He captured how ZPMC management communicates the gravity of producing a quality product to its workers: Hanging high above the outside of one of the warehouses, a red banner reads, “Regulations is glorious, working recklessly is disgraceful.”

Where Paiva caught moments of friendship and camaraderie on the construction yard, emotion creeps into the otherwise stark task of constructing one of the most controversial and complex suspension bridges in the world.

Workers are clad in tangerine jumpsuits, emblazoned with “ZPMC” on the back, and in overalls a cheerier shade of Folsom Prison orange. They flash smiles in some photographs as they catch their breath from the hectic pace to pose in groups.

While subcontracting with ZMPC and using foreign steel was expected to save hundreds of millions overall, manufacturing problems have gnawed away at the potential benefits, with tens of millions needed to pay for performance incentives, reforming inspection procedures, and keeping quality engineers overseas and on the job.

The project has required scores of American workers from ABF, Caltrans, and its subcontractor to relocate to China for extended periods, especially as the inspection staff grew to respond to weld-quality issues.

In addition to the inspectors from ABF, Caltrans, and its subcontractor—currently Caltrop, which began project oversight last December—ZPMC maintains its own quality-control staff. And there are at least 250 inspectors—about 200 from the prime contractor and 45 from Caltrans—working with ZPMC inspectors to ensure the millions of welds are up to par.

In an effort to correct the chronic welding problems, an expensive “green tagging” process was devised whereby small green tags were attached to components as they passed quality control testing. That process will cost at least $17 million by the time Chinese fabrication is completed.

Delays related to a June 2009 shipping date undermined the confidence in the green tagging process, which was supposed to prevent this type of slowdown in the inspection chain. That confidence continued to erode as target dates for shipments from Shanghai slipped ever further into autumn.

American Bridge estimates that the barge carrying the first shipment of the 500-ton deck sections from Shanghai will sail by the end of the year—so, weather permitting, we can expect to see them passing through the Golden Gate by January or February.

Pieces of the tower, which are fabricated in smaller sections roughly 100 feet high, aren’t scheduled to arrive until late spring or early summer.

By the time all the bridge pieces are delivered, fabrication costs will have ballooned by $100 million, and probably millions more.

Still, the bridge’s overseers believe that building in China will turn out to be a good deal for Californians.

“The simple fact is, despite the fact that we got a bid for domestic steel, I’m not sure that there is a domestic steel fabricator that could do what ZPMC is doing” in terms of scale and their capability for the “massivity of this project,” said MTC executive director Steve Heminger.

This story is part of a special reporting project that first appeared Dec. 8, 2009, in the San Francisco Panorama, a single-edition broadsheet newspaper published by McSweeney's. The project, conducted by SF Public Press, was researched and written by Patricia Decker and Robert Porterfield with the assistance of Mike Adamick, Andrew Bertolina, Richard Pestorich and Michael Winter. The project was supervised by Public Press director Michael Stoll. More than 140 people helped to fund this reporting project by donating through Spot.Us.