The sidewalk on Hyde Street was jam-packed with people hustling for survival. A wiry young man in cutoff shorts, his legs pockmarked by needle wounds, barreled through the crowd. A tall slender middle-aged man clutched a wad of bills, eyes alert.

Damon, a 47-year-old Black man, was selling Warriors jerseys amid the chaos just a few blocks from City Hall. “I haven’t caught it, I been cool,” he said. “I feel like the people who get it are people going on trips. I have little chance of getting it.” Damon, who gave only his first name, has lived on the Tenderloin streets since 2005.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Damon walks his bicycle down a busy sidewalk in the Tenderloin neighborhood in late June, selling Warrior jerseys for $7. He packs his merchandise on his bike, which he used for transportation to avoid public transit and the coronavirus, he said.“You see more people living in tents now,” he said. Asked if the city is addressing his needs, Damon was blunt: “No.” What do people in the Tenderloin need most now? “More rooms. More rooms.”

Nearby, longtime resident Virlea Johnson spooned bites from a melon cradled in her arm. The pandemic has been “a wake-up call” to long-festering problems, she said. “People are out here exchanging money, they don’t wash their hands,” then touch their faces, she said. In her residential hotel on McAllister Street, she has found “people urinating in the elevator,” and outside, “I constantly have to be aware of human feces on the ground.”

In a pandemic that mandates physical distancing, survival in the poverty-suffused Tenderloin is endangered by relentlessly overcrowded conditions, a dearth of open public spaces and limited mobility.

Every corner of life here is packed tight: sidewalks, streets, homeless tent encampments, apartment buildings and single-room-occupancy hotels, where residents have their own rooms but typically share bathrooms and kitchens. By far the most densely populated neighborhood in San Francisco, the Tenderloin is home to 45,587 people per square mile, almost 2.5 times the citywide density of 18,939 people per square mile. Neighborhood residents suffer the city’s second-highest rate of COVID-19 infections — eclipsed only by the Bayview — and five times that of neighboring Nob Hill.

Based on the city’s own risk assessment metrics, the neighborhood is on the precipice of a COVID-19 disaster. According to San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, COVID-19 risk factors include “living in crowded conditions, being unable to limit outings, being over the age of 60, and having certain preexisting health conditions.” In one census tract in the heart of the Tenderloin, the average age is nearly 56. Throughout the district, the median age is 43, compared with 35 for the city as a whole.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

For the past two years, Virlea Johnson has lived in a single-room-occupancy hotel on McAllister Street in the Tenderloin. Before moving into the residential hotel, Johnson lived in a tent in the same neighborhood. “You have to be cautious inside and outside,” she said. “The things that happen out here also go inside the buildings.”Public space is even more cramped by the partial closure of Boeddeker Park, the neighborhood’s lone green space, due to pandemic concerns. One recent improvement: More than three months after the city approved a “slow streets” program to expand physical space for pedestrians, the Tenderloin finally received this density relief this month with the partial closure of Jones Street from O’Farrell Street to Golden Gate Avenue, with promises of additional full-block closures on Saturdays to create play areas for children.

Homeless people are dying at a much higher rate than in 2019, said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness. A recent analysis by the San Francisco Chronicle found 125 homeless people have died this year — many on the streets, but some in temporary city-provided hotel rooms — at “more than double the number in the same time period last year.”

When city shelters closed their doors to limit COVID-19 outbreaks in March, the number of shelter beds citywide plunged from 2,500 to 1,000, according to the Coalition on Homelessness. By early June, the number of tents in the Tenderloin had exploded to more than 400.

In response to the surge in tents, UC Hastings School of Law sued the city, arguing that the threat of coronavirus spread in the neighborhood posed an immediate public health crisis. More than 100 former UC Hastings students blasted the lawsuit as an attack on homeless people, warning that the move “will displace the Tenderloin’s houseless population and distribute it throughout San Francisco, limiting these individuals’ ability to organize and support one another,” while also expanding “police repression of our unhoused neighbors, many of whom are people with disabilities, African American, and Latinx people displaced from their homes by economic and political violence.” In a June 11 settlement, the city promised to remove 300 tents and relocate the people living in them by July 20.

Now, after a push to get people into shelters and hotel rooms — available to those who qualify because of age or underlying health conditions — San Francisco’s official “tent count” in the Tenderloin stands at 105. The city reopened a temporary shelter at Moscone Center in April, for a maximum of 200 people, but it has been a locus of resident complaints of unsafe conditions and meager COVID-19 testing.

Demographics worsen COVID-19 health risks

“We’re actually seeing the effects of three pandemics,” said Joe Wilson, executive director of the nonprofit Hospitality House, based in the Tenderloin. “The existing pandemics of poverty and racism, now completely exacerbated and overwhelmed by the public health pandemic.”

The city’s Department of Public Health notes that COVID-19 “has disproportionately impacted communities of color” locally, throughout the state and nationwide. And in these communities, “structural barriers to home ownership, education, jobs, and health care impact current housing conditions, social determinants of health, and job opportunities.” Poverty in the Tenderloin is more than double citywide levels — and in some parts of the neighborhood, two-thirds of residents live in poverty.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

People congregate on the sidewalk to chat and sell found goods outside the Tenderloin Museum at the corner of Leavenworth and Eddy streets in late June.“People of color are overrepresented in the homeless population,” said Wilson. “Overrepresented in lower income folks. Overrepresented in safety net programs. If any crisis hits us, it overwhelms those systems and overwhelms people of color.”

According to the city’s annual point-in-time homelessness count, Black residents represent more than 37% of San Francisco’s homeless population but only 6% of the city’s total population.

Supervisor Matt Haney, whose district includes the Tenderloin, said the racial dimensions of the neighborhood’s homelessness crisis are on display every day: “If you walk around the Tenderloin after 6 p.m., most people on the streets are Black — there’s no way to look at that and not see the connection to racism.” Many of these people, he notes, “have been displaced from the Fillmore, Bayview and other areas. The people who are most vulnerable to COVID-19 are the people most vulnerable and impacted by racism and violence and inequality.”

Dying in the streets

While the Tenderloin has so far eluded a mass outbreak, the pandemic has magnified pre-existing struggles. Dr. Juliana Morris has treated many Tenderloin residents who are now staying in hotels as part of the city’s COVID-19 shelter strategy. “Because the pandemic has created economic crisis for so many people living in poverty and living on the margins of homelessness and housing instability, it’s causing more people to be homeless,” she said.

“I did have some patients that were marginally housed, living with friends or relatives, but not officially renting, who were asked to leave when COVID started, and had no choice but to go to the streets,” Morris said. The shutdown of shelters was a major contributor to rising homelessness in the Tenderloin after the pandemic started, she added.

Dr. Barry Zevin, director of street medicine and shelter health for the city, said homeless people’s suffering has intensified during the pandemic. “I’m seeing more people dying in public view,” he said. While much of the Tenderloin is heavily crowded, overall there are fewer people walking the city’s streets to “notice someone in extreme distress,” Zevin said — meaning more homeless people may die in the streets now without anyone calling for help. “It’s a lot easier for someone to get sicker and sicker, and maybe die, than it was a few months ago.”

About half the deaths among homeless people this spring have occurred outdoors, a higher portion than in previous years, said Department of Public Health spokeswoman Jenna Lane.

Cramped housing, dust and mold

The Tenderloin’s crowded conditions are compounding stress for housed residents, too. Many describe living in tightly confined spaces — often clouded by dust or mold, which can exacerbate COVID-19 respiratory hazards — with little relief outside on densely packed streets.

“You definitely hear a lot of people saying, ‘I don’t feel safe going out of my door,’ and ‘the neighborhood is a risk for me,’” said Sara Shortt, director of public policy and community outreach at the nonprofit Community Housing Partnerships. She recalled members of Tenderloin families telling her, “I don’t feel safe taking my kid out on the streets because it’s so crowded.”

For some residents, time on the sidewalk provides relief from compact living quarters. Standing outside the historic Hamlin Hotel on Eddy Street, 66-year-old Duke Williams smoked a cigarette. He lives in a small room in a single-room occupancy hotel. “It’s tight,” he said, pointing at the concrete: “See those three squares on the sidewalk? You’re standing in the middle of the room.” Like residents in many buildings in the Tenderloin, Williams shares a bathroom and kitchen space with others, adding to potential COVID-19 exposures.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Duke Williams passes time outside his home opening in late June. Williams moved into the Hamlin Hotel in 1991 and has made a lot of friends in the neighborhood. But during the pandemic, the single-room-occupancy hotel has prohibited visitors to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus. “I used to get a lot of company,” Williams said. “I miss them. I would get five good visits a day.”Worsening matters, the building has been under renovation throughout the pandemic, according to Williams. “I don’t think the tenants are too safe in the building right now, with all this dust flying around,” he said. “They are cutting walls. There’s too much dust flying around in the air for me.” By each day’s end, he said, there’s “a pile of sawdust on the floor” in his room.

A few blocks away, at the Essex Hotel, another single-room occupancy residence, Jennifer Trossell, 49, said chronic mold throughout her 475-square-foot room was making her sick. She was recently diagnosed with emphysema. “I see mold everywhere,” she said. “I can’t even breathe, I’m up all night gasping for air.” Trossell said she recently received an accommodation to move to a different building, but she didn’t know when that would happen.

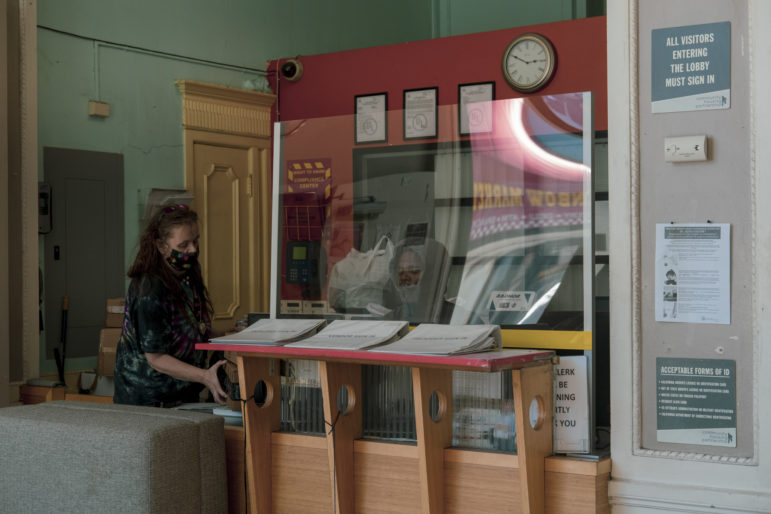

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Kristi Banks picks up her mail from the reception desk of the Essex Hotel. To prevent the spread of the coronavirus, the hotel installed plexiglass walls and posted safety guidelines. Residents must wear masks when entering the building. The hotel has about 100 rooms on seven floors.Shortt, of Community Housing Partnerships, acknowledged that single-room-occupancy hotels “are definitely not conducive to social distancing — the opposite. People are sharing bathrooms, kitchens and community rooms,” and narrow hallways, she said, “living at risk every day in their units.” In the pandemic, she added, some residents have become further isolated by avoiding shared kitchens and community rooms.

Living in a ‘soup of despair’

“The squeeze on shelter has led to “an increase in stress, despair and hopelessness,” Zevin said. Before the pandemic, “resources were already scarce,” he said, but “there was always hope” that people could get shelter at least for a night or two. Now, “when people see the look on my face that there is really nothing, in some ways that kind of despair is as contagious as COVID,” he said. “People are living in that soup of despair every day, along with their desperate conditions.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Kristi Banks lives with her companion dog Jack, aka “Carjack,” at the Essex Hotel at Ellis and Larkin streets. The single-room-occupancy hotel has been their home for more than 10 years. Banks and Jack are inseparable. The dog gives her a sense of purpose and a schedule in her life, Banks said.In front of the Essex on a recent afternoon, resident Kristi Banks expressed another COVID-19 concern intensified by confined living quarters: “I have some issues with depression and it certainly hasn’t been good for that,” she said while reining in her friendly but rambunctious dog Jack. “It was awful. You’re by yourself and our rooms are small. It got pretty dark at times.”

Seeking space and safe interaction, Banks has volunteered at the nearby Healing Well, recently helping to prepare 57 bags of produce for hotel residents like her. “There’s food insecurity around here.”