Preserving art matters to Michael Johnstone, a San Francisco-based painter, costume designer and photographer, who has been living with HIV since 1982. Johnstone moved to San Francisco in 1979, a few years before the AIDS epidemic seeped through the city.

“I took care of a lot of people, a number of people that were passing away were artists, and their work ended up in thrift stores,” Johnstone said.

He said that since artists were dying at such a fast rate during the epidemic and there was not always time to deal with every aspect of their estates, he would see collections of their work scattered or never archived.

To help artists who were suffering from life-threatening illnesses, a collective of artists, art collectors and gallery owners including artist Daniel Goldstein, Ruth Braunstein of Braunstein/Quay Gallery, Jeffrey Fraenkel of Fraenkel Gallery of Photography, Paule Anglim of Gallery Paule Anglim, Rena and Trish Bransten of Rena Bransten Gallery and several others, began convening at local art spaces in the city in late 1980s. Their mission was to find a means to record the existing works of artists with AIDS and provide them with the materials they needed to create new ones.

Goldstein, with the help of the other contributors, grew the group into a fullfledged nonprofit called Visual Aid in 1989, and the organization has been supporting hundreds of Bay Area artists since then.

Johnstone has been a Visual Aid artist for at least 18 years and served as a client liaison board member for a few years during that time. “Initially, when my health was very poor and my demise seemed imminent, I at least knew that the slides of my work, the things I had been making, would be documented somewhere,” he said.

In addition to archiving his work in the form of photographic slides, Johnstone said that Visual Aid has helped him buy art and photography supplies, connect with other artists and find opportunities to showcase his work.

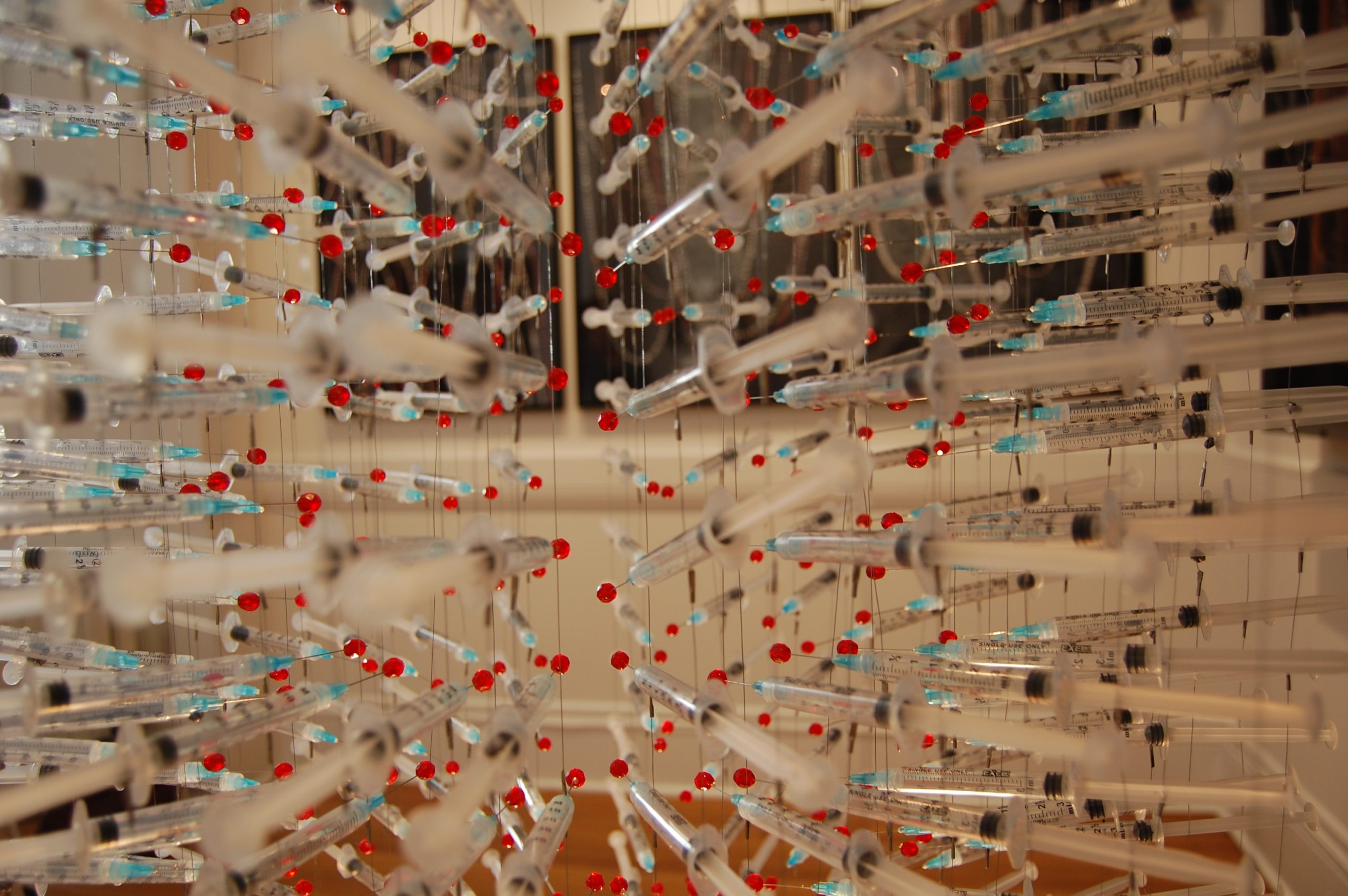

Johnstone collaborates with his partner and another Visual Aid artist, David Faulk, to create and photograph elaborate costumes made from everyday items like straws, beads and plastic flowers.

He said the organization also helped him get a grant through the Horizons Foundation, a philanthropic organization in San Francisco that provides grants and other services to the LGBT community, to show his work at the California Institute of Integral Studies, a private college in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Following the show at the college, Johnstone said the James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center at the San Francisco Public Library included his artistic works in its archives.

“When dealing with an illness where it seems imminent that you’re not going to live,” Johnstone said, “and it happens two or three times, I always have my art to get me through it. Also, there’s an aspect of disintegration when you’re dealing with a long-term illness. You see things diminish. You see rooms get smaller. You see people disappear — at least back in those days you did. It’s harder to get out and be social. It’s really hard to organize an art show.”

He said that the organization helped him integrate back into the art community by providing access and opportunities to art exhibitions and group activities.

While Visual Aid runs on an annual budget of about $340,000 with two full-time and one part-time staff members and volunteers, it currently supports 75 artists. The process for an artist to join the organization, however, is rigorous.

“It’s almost like art school in the sense that artists need a portfolio which shows a body of current work that’s outstanding, really proves that art is their vocation and shows that they’ve been creating art over a period of years,” said Julie Blankenship, executive director of Visual Aid. “We have very high standards, and that’s because once an artist joins our program, it’s pretty much a commitment for lifetime on our part.”

She said that the organization sometimes requires a letter from a physician confirming an artist’s illness.

Blankenship said that 95 percent of Visual Aid artists live on low or very low income and that most also live on government funded disability income. She added that 78 percent of the artists are living with HIV and 1 in 6 does not have health insurance.

The organization provides vouchers for the artists that can be used at various art supplies stores, and also has an Art Bank, a storehouse in the office that is filled with supplies like paints and canvases for Visual Aid artists.

She said that in the past the organization has put on various thematic exhibitions featuring the works of the group’s artists.

“We noticed that several artists had used the get out of jail free card from Monopoly, so we did a big exhibition called ‘Get Out of Jail Free,’ and it was kind of imprisonment as a metaphor for illness, social injustice, isolation,” she said.

While the works of Visual Aid artists are exhibited at other Bay Area galleries, some are also found in the organization’s own gallery that opened last year. The current exhibition, “A Thin Line: Extinction, Survival, Transformation,” features works by artists Daniel Goldstein, David King, David Wojnarowicz and Philip Zimmerman.

Blankenship said that opening the gallery enables the organization to create more risk-taking, edgy exhibitions.

She said that in addition to continuing its existing programs, the nonprofit is planning to roll out a new vision program to provide free eye checkups for the artists.

“We really work to create a sense of abundance which is missing in the lives of most of us, and especially people who are ill and are artists,” she said.