At least 400 people living outside have been on a waitlist for supportive housing for more than a year. San Francisco has more than enough rooms for all of them. The San Francisco Public Press and ProPublica investigate.

FIND THE STORY HERE

FOR INTERVIEWS: Nuala Bishari, reporter — 415-860-7915 or [email protected]; or Lila LaHood, publisher — 415-846-3983 or [email protected]

VISUALS: Nuala Bishari is available to meet for interviews virtually or in person.

MEDIA ASSETS: See below.

SAN FRANCISCO (Feb. 24, 2022) — For more than a year, San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing has wrestled with a growing number of vacancies. Despite having more than 1,600 homeless people on the waitlist for these units, 888 sit empty. By the department’s own estimation, at least 400 of those people have been waiting for more than a year — far beyond its own goal of 45 days.

Nuala Bishari — a reporter for the San Francisco Public Press and a fellow with ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network — spent 10 months investigating the city’s methods for getting people out of tents or other short-term shelter and into permanent supportive housing.

Today, the two newsrooms jointly published “In San Francisco, Hundreds of Homes for the Homeless Sit Vacant,” the first part of Bishari’s investigation of the path from homelessness to housing, in which she found:

- Vacancies have doubled in the past 15 months in San Francisco’s permanent supportive housing — units it has purchased, leased or contracted out to private service providers.

- Filling those empty rooms would cut the waiting list by more than half — and it would be enough to house roughly one in every eight homeless people in the city.

- Officials acknowledge that at least 400 people approved for permanent supportive housing have been waiting more than a year.

- The $598 million annual budget for the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing has tripled since the department was created in 2016. The city now has more than 8,000 supportive housing units, but it’s still not enough for all those in need.

During the pandemic, the process for moving people into empty units was complicated by new rules prioritizing housing for people living in shelter-in-place hotels over those living in tents, error-prone tracking software, slowness in transferring applications to service providers, unresolved maintenance issues in empty units, requirements for identification and documentation that are challenging or impossible for someone living on the street, and a chronic shortage of case managers.

High-resolutions images

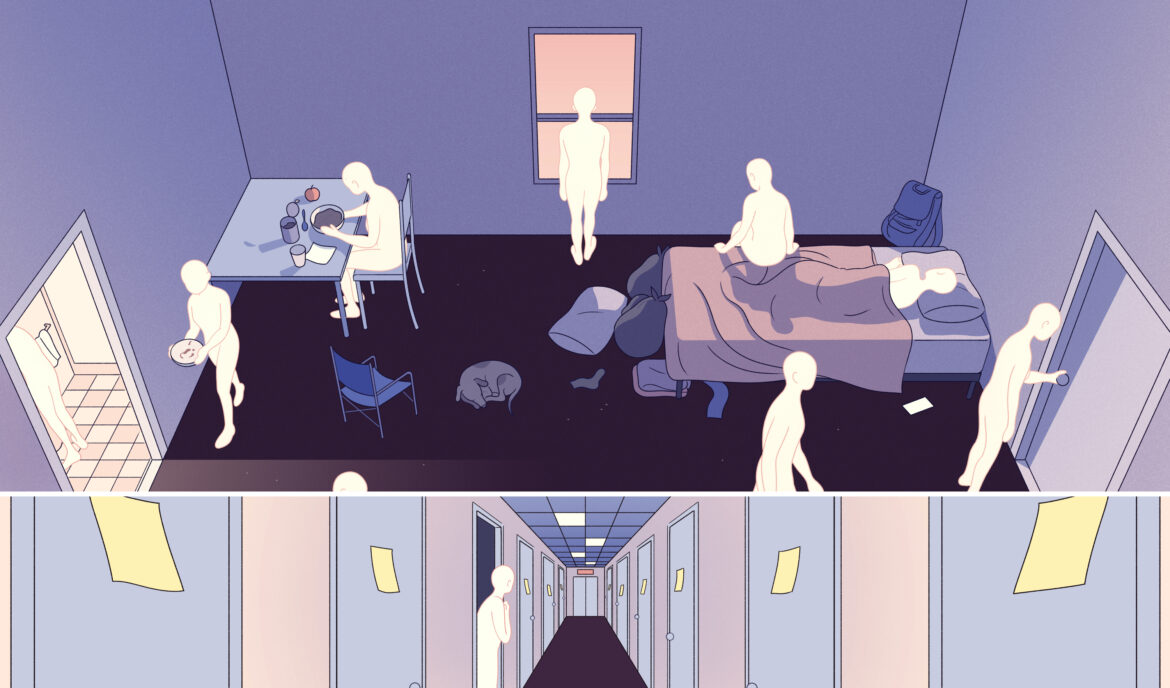

Bianca Bagnarelli, special to ProPublica

Bianca Bagnarelli, special to ProPublica

Bianca Bagnarelli, special to ProPublica

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

A view inside the sanctioned tent encampment where Ladybird lived for 15 months, starting in late 2020.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

A tall fence encircles a city-sanctioned tent encampment in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Inside one of San Francisco’s permanent supportive housing buildings, the kind of housing both Ladybird and Marquita Stroud hope to move into.