Earlier this year, the San Francisco Public Press featured Tantay Tolbert in “Driving Home: Surviving the Housing Crisis,” a photojournalism project by Yesica Prado documenting the experiences of people living in vehicles in the Bay Area. Prado followed up with Tolbert to find out how her life has changed in recent months.

Explore images by clicking through the viewer above, or see the entire photo essay here on a single page.

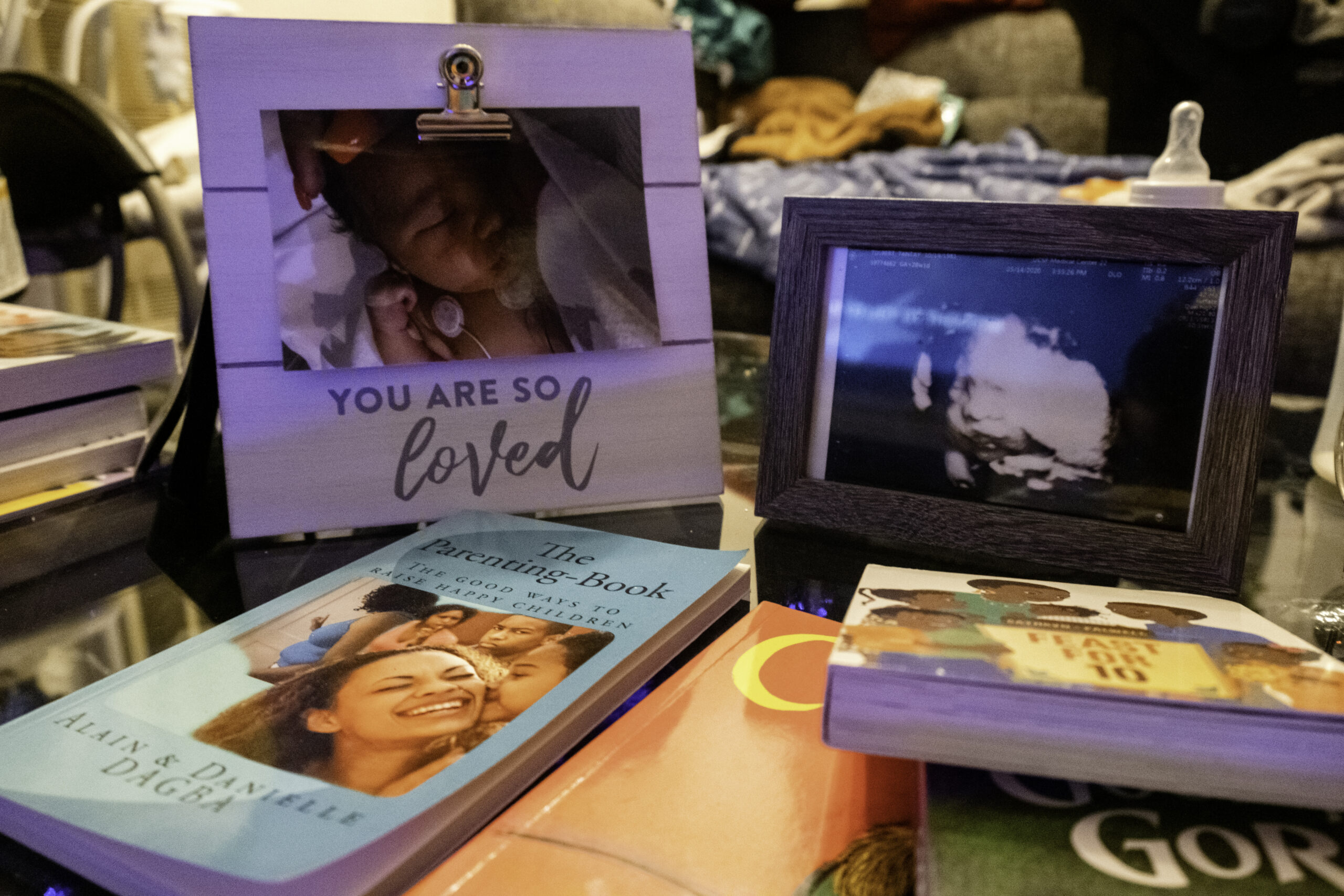

In a dimly lit living room, Tantay Tolbert reaches for a warm bottle of milk on the glass coffee table. Her month-old baby, Supreme Samuel Lloyd-Vaughn, softly cries in her arms. She caresses his black curls as she tilts the bottle into his mouth. “You were hungry, my baby?” Tolbert asks with a smile. “You eat a lot, baby.”

It’s an ordinary day for Tolbert — comforting Supreme and dressing him in cute clothes. And yet, what seems ordinary now represents dramatic change and newfound stability.

On June 16, Tolbert moved into her new apartment after a year of living in a recreational vehicle that she parked on various streets in San Francisco’s Bayview neighborhood.

Inside her brick home, the world moves slower than it did when she was living in an RV, Tolbert said. These days, she wakes up to her son’s cries or giggles instead of San Francisco police officers banging on her door telling her to move her motorhome.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press and CatchLight Local

Tantay Tolbert changes her son’s clothes on the dining room table in her new apartment. In March, the Homeless Prenatal Program in San Francisco offered her a hotel room for 90 days, and this became her first step into stable housing. After the hotel room, she transitioned into subsidized housing. “They looked out for me during the time of my pregnancy,” Tolbert said. “They gave us vouchers and made sure we had something to eat. It was catered food every day. It was blessed.” On June 16, Hamilton Families gave Tolbert the keys to her new apartment. “On Tupac’s birthday. It’s a Black holiday,” she said. A time to celebrate.Tolbert left a tedious life behind when she moved into the apartment: No more quarrels with surrounding businesses. No more daily chores hauling water for bathing and cooking, and gasoline for running the generator to power small appliances. No more searching for safe parking spots. No more hunting for dumpsters.

A baby on the way

When Tolbert found out she was pregnant, finding secure housing became her top priority. Hamilton Families, a San Francisco nonprofit focused on providing housing for homeless families around the Bay Area, gave Tolbert keys to a one-bedroom apartment in the city of Richmond. Previously, Tolbert had turned down a parking spot for her motorhome in San Francisco’s Vehicle Triage Center, because she found the program’s rules and regulations to be too strict. But with a baby on the way, she was determined to find a stable home.

“I just basically pushed the pavement,” Tolbert said. “I went to all the programs and got into all their systems. Talked to everybody.”

Through a subsidy support program, Hamilton Families secured a lease for Tolbert and paid her first and last months’ rent. Under the initial 12-month agreement, Tolbert was set to pay $546 — about a third of her current income — each month. The monthly payments fluctuate based on her earnings, which she updates in reports to the nonprofit every three months. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the program has been extended for an additional year.

For nearly the next two years, Supreme has a safe place to grow up.

Tolbert’s one-bedroom apartment has a kitchen, pantry, dining room, living room, bathroom and a shared backyard. Three flat-screen TVs. A functional oven. A bathtub. Spacious rooms decorated with her personal touch in shades of black and red. A closet full of clothes.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press and CatchLight Local

Tolbert fixes her baby’s Chanel-print outfit before going out for the day. Due to high blood pressure and sugar levels, Tolbert was induced into labor with a C-section two months early. Supreme Samuel Lloyd-Vaughn, her first child, was born July 19. He weighed 6 pounds, 7 ounces.Tolbert said the apartment has made a big difference and simplified her day-to-day life. “Now I don’t have to use an ice chest. I got a refrigerator,” Tolbert said. “I get to store my food much longer. It’s not going straight to waste. I am able to cook a full course meal. Store more food for the following day.”

The path for housing from RV to apartment living involved many steps — with added twists due to the pandemic. In March, Mayor London Breed enacted a shelter-in-place order for San Francisco mandating residents stay home to slow the spread of COVID-19. The city developed programs to provide hotel rooms or approved camping sites for thousands of unhoused residents — but many people struggled to secure shelter through either program, and a large number of the hotel rooms remained empty. As an expectant mother, Tolbert had better luck. She was granted a hotel room for 90 days by the city’s Homeless Prenatal Program.

Social programs and a side hustle

“They looked out for me for the time of my pregnancy,” Tolbert said. “They gave us vouchers and made sure we had something to eat. It was catered food, every day. It was blessed.”

That same month, Tolbert left her job cleaning elevators at the Civic Center BART station for nonprofit Urban Alchemy because she was afraid of contracting the virus in such an enclosed environment. Without steady income, she relied on homeless service providers, public benefits and a side job selling used vehicles acquired through public auctions to make ends meet.

While her car sale business is always fluctuating, the public vouchers give her a reliable way to feed her family. As an individual, Tolbert had received CalFresh benefits, which gave her $190 every month. After Supreme was born, CalFresh increased her monthly budget to $350. As a mother, she also became eligible for WIC benefits, a special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children.

Tolbert receives additional assistance from California’s Black Infant Health program, which gives her $150 in grocery food vouchers every two months. She can only use those vouchers in San Francisco, so she travels across the Bay Bridge to shop with those vouchers, which she uses to stock her pantry with nonperishable goods; she uses her monthly CalFresh and WIC benefits to buy other provisions. While social services keep her family from experiencing food insecurity, Tolbert depends on her car sales income to pay her other bills and living expenses.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press and CatchLight Local

In the baking aisle, Tolbert scans a shelf of peanut butter jars looking for brands that she is eligible to purchase with her WIC benefits, which she can only use to buy specific food products from designated stores, preventing her from accessing healthier choices. She spends 20 minutes looking for items from the list on her phone, but only finds two in stock.In San Francisco, Black infants are almost twice as likely to be born prematurely (13.8%) compared with white infants (7.3%). Pacific Islander infants have the second-highest preterm birth rate of 10.4%. Furthermore, Black families account for half of the maternal deaths and over 15% of infant deaths, despite representing only 4% of all births in the city.

Planning for a new life

Supreme was born two months early. Due to high blood pressure and sugar levels, Tolbert was induced into labor early and had a C-section. The baby was not born with health complications, but he was frail. During her pregnancy, Tolbert was fortunate to have a hotel room, a case manager, a housing navigator and access to other supportive health services. After 90 days, she was transitioned into affordable housing. When she looked for housing on her own, even with income from her job, she had struggled to find an affordable unit and a landlord who would rent to her.

“Nobody wanted to rent to me because I didn’t have any credit,” she said. “And also, you know, I had evictions before. Those two things were always blocking my blessing. I had the money. I just didn’t have the paperwork to back me up.”

Now, Tolbert is grateful for the reprieve and is taking steps to clear her name. Using some of her unemployment benefits, she spent $8,500 to pay overdue state taxes and accumulated fees.

Tolbert is planning ahead; she wants to keep her current home. In two years, the monthly payments will triple, and she will have to pay the full rent: $1,600 each month plus utilities. “I definitely would keep the apartment,” she said. “The baby needs a roof over his head. And so whatever welfare has given me, plus selling cars, will be helping me provide for my rent.”

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press and CatchLight Local

Tantay Tolbert poses for a portrait with her son Supreme inside her 1977 Chevrolet Impala in front of her apartment in Richmond. She is hoping to get $10,000 when she sells this classic vehicle. Since the pandemic started, Tolbert and her partner have increased their car sales. “People are buying equity, and they can get to where they need to go,” she said. Tolbert says she has used some of her unemployment benefits to buy cars at auctions. She and her partner fix up the cars and sell them to people — some of whom are using their own unemployment benefits to pay for the vehicles. “We’ve been doing it since I was 21. I’m 38 now. We can do this with our eyes closed,” Tolbert said confidently. “This has been the whole solid foundation.”San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing has a goal to end family homelessness by December 2022. In 2019, the city’s annual point-in-time count documented 98% of homeless families living in shelters, with 2% living unsheltered on the streets inside tents and vehicles. Looming evictions as a result of the coronavirus pandemic could increase the unsheltered population.

Tolbert said she doesn’t take her new life for granted. She got a whole new start and hopes to return to school to pursue a college degree. But she said, she won’t forget the many things she learned while living in her RV.

“It humbled me. It made me more aware of my surroundings,” Tolbert said. “And made me, you know, just cherish electricity from PG&E.”

“I don’t have to go back to the old life,” she said.

This story is part of “Driving Home: Surviving the Housing Crisis” and was produced in collaboration with the Bay Area visual storytelling nonprofit CatchLight through its CatchLight Local Initiative. As a CatchLight Local Fellow at the San Francisco Public Press, Yesica Prado examined the culture of vehicle living in San Francisco and Berkeley. Her fellowship work has been featured by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and by the Artists Against an #Infodemic Campaign, which aims to improve access to locally relevant public health information. The CatchLight Local Initiative is funded by the Kresge Foundation, The GroundTruth Project, the Facebook Journalism Project, the Neda Nobari Foundation and the Lisa Stone Pritzker Family Foundation.