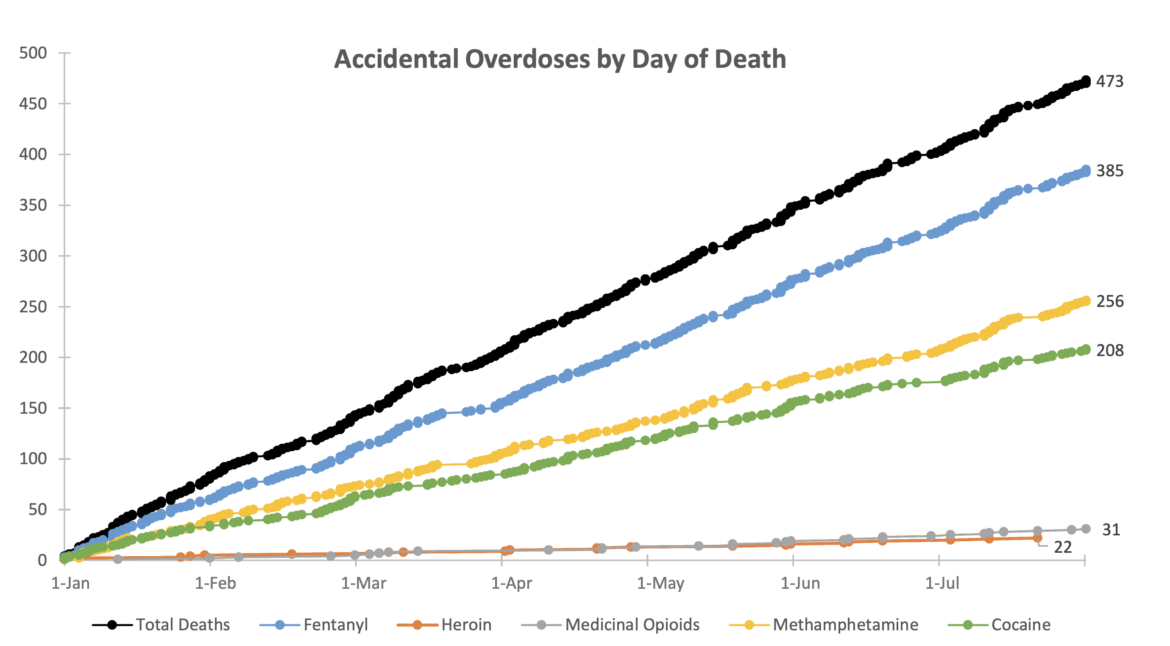

Updated 8/24/23: This story was updated to include a new chart from the chief medical examiner’s updated report. See the note at the end of this story for details.

Accidental drug overdose deaths continue to torment San Francisco, according to data released Tuesday by the city medical examiner’s office. The alarming statistics come as San Francisco’s supervisors clash over an effort to redirect neighborhood harm reduction center funds to jail treatment programs.

While June saw the lowest monthly number of overdose deaths this year, 54, in July it climbed back up to 71. With 473 overdose deaths this year, San Francisco is on track to surpass its highest recorded number of overdose deaths in a calendar year — 725 in 2020.

Last spring, harm reduction advocates warned city officials and law enforcement that arresting people who use drugs could lead to increased fatal overdoses. They were responding to a strategy that the San Francisco police and sheriff’s departments launched in May called the Intoxication Detention Pilot Program, which jails people openly consuming drugs or showing signs of intoxication. The goal of the intervention, officials said, was getting them into treatment.

In an Aug. 4 letter to Mayor London Breed, Dorsey, who is in recovery from drug addiction himself, pushed to take $18.9 million in the recently adopted two-year budget away from new neighborhood harm reduction centers and give it to jail treatment programs. Dorsey’s petition has renewed criticism over the strategy to jail people who use drugs.

Sara Shortt, a coordinator with the San Francisco Treatment on Demand Coalition, said Dorsey’s new stance was in “direct contradiction to evidence-based public health recommendations, developed in partnership with community stakeholders.”

Addiction health experts say that a police crackdown on drug use is dangerous because it will drive people to consume in hiding, which increases the risk of death since an overdose is less likely to be noticed and thus reversed.

Cracking down on street drug sales can also increase overdoses, experts say, because users could end up relying on unfamiliar sources whose drugs may be more potent or unknowingly tainted with fentanyl.

Of the 71 fatalities in July, 62 people succumbed to fentanyl overdoses, the second-highest number since the city began reporting monthly overdose numbers in 2020. The record, 65, was set in May.

In September 2022, the San Francisco Department of Public Health released a three-year overdose prevention plan. It aimed to reduce overdoses by 15%, increase people on medications for addiction treatment by 30% and reduce racial disparities in overdose deaths by 30%.

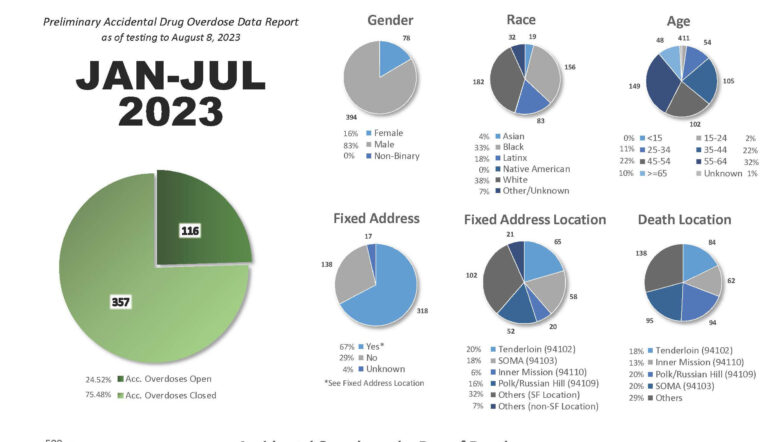

Today, overdose deaths continue to affect the Black community disproportionately. While Black people make up 5% of the city’s population, they make up 33% of people who have died of overdose this year.

Courtesy of the San Francisco Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner’s preliminary accidental drug overdose data report indicate the demographics of people succumbing to accidental fatal overdose in San Francisco from Jan. 1 to July 31.The plan also proposed new harm reduction centers — called “wellness hubs” — as drop-in settings to provide safe consumption spaces and connections to treatment, housing and other benefits.

In his letter to the mayor, Dorsey wrote that he decided to lobby for prioritizing jails because plans for the wellness hubs had changed to omit supervised consumption sites. The sites would have allowed people to consume drugs under supervision to ensure they received immediate care if they overdosed. But officials scrapped the plan after City Attorney David Chiu refused to sign off, warning that state and federal laws prohibit them.

“While I remain a staunch supporter of supervised consumption site, as an appropriate and necessary response to our record-shattering fatal drug overdose crisis,” Dorsey wrote, “the inability of our City and its nonprofit partners to assume the requisite legal risks at this time to offer supervised consumption services diminishes the value of moving forward with the ‘half-loaf’ approach now contemplated by DPH for Wellness Hubs.”

Dorsey was also critical of the decision to reduce the number of sites from six citywide to one in South of Market, which is part of his district.

“One of the more compelling value propositions for the Wellness Hub model was to distribute access points for services for drug users among multiple affected neighborhoods, so as to avoid centralizing a massive public nuisance,” he wrote.

Dorsey did not respond to a request for comment.

HealthRight 360, with which the city contracts to provide treatment services, issued a statement opposing jailing unhoused people solely for public intoxication, adding “it is especially egregious when it comes at the expense of resources intended to serve the most vulnerable members of our community.”

Dorsey also received backlash from colleagues on the Board of Supervisors. Supervisor Dean Preston criticized his plan in a tweet saying “This reversal comes months after City leaders united to call for wellness hubs. Now some are trying to divert the funds to arrests/incarceration of users.”

In a press release, Supervisor Hilary Ronen called Dorsey a “grandstanding politician.” She said the Sixth Street Harm Reduction Center, operated in Dorsey’s district by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, is now seeing 500 requests a day for services.

“The funded Wellness Centers are designed to meet this demand,” she stated.

Shortt said she believed that Dorsey’s lobbying was partially motivated by the years he served as spokesperson for the San Francisco Police Department.

“It’s clearly influencing his politics at City Hall,” Shortt said. “It’s really hard not to look at something like this and think that he’s also doing it out of an interest in bolstering the police budget and advocating for law enforcement solutions.”

This article is part of a series on San Francisco’s overdose crisis and prevention efforts, underwritten by a California Health Equity Fellowship grant from the Annenberg Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California.

Updated 8/24/23: This story was updated to include a new chart from the chief medical examiner’s updated report. In the new chart, “cocaine” replaces the term “series 6.” “Total deaths” refers to the number of people who died of accidental overdose from all drugs, including those not specified in the chart. Each point along a drug type line refers to a death involving that drug either alone or in combination with another drug. Individual deaths involving multiple drugs are represented along multiple drug type lines.