As the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing scrambles to find placements for the more than 2,300 residents of its shelter-in-place hotels, little attention has been paid to the people who work at those sites. Nonprofit organizations that run the hotels are working diligently not just to identify exits for residents, but to keep their staff, many of whom have worked at these nonprofits for decades.

When COVID-19 hit, San Francisco closed its shelters and navigation centers to prevent the coronavirus from spreading. Many residents from those facilities were relocated to shelter-in-place hotels — and the shelter staff went with them. But now that the city has declared that the hotels must close, and with shelters operating at a fraction of their original capacity, there’s nowhere for staff to go.

Last week, the city’s homelessness department hit pause on its plan to shut down shelter-in-place hotels, providing little clarity on a new timeline. But if the city proceeds with its proposed wind-down plan, nonprofits will face mass layoffs. And that will be hard on hotel employees, many of whom don’t have enough savings to cover more than one month’s worth of living expenses, said Jane Bosio, a union representative for OPEIU Local 29, which represents hundreds of shelter-in-place hotel employees.

“This is going to devastate these people’s families,” she said, adding that many workers have experienced homelessness themselves. “You have someone who has worked their way up to dedicate decades of their life to these programs, and you’re going to put them out on the street.”

As many as 80 full-time employees at Episcopal Community Services, which runs eight shelter-in-place hotels, three of which are earmarked for the first round of closures, could lose their jobs, Bosio said. And that isn’t the only hotel provider facing widespread layoffs.

It’s an issue that’s been keeping Laura Valdez, the executive director of Dolores Street Community Services, up at night. When the pandemic arrived, her organization’s emergency overnight shelter at St. Mary and St. Martha Lutheran Church on South Van Ness Avenue ramped up to provide round-the-clock services at the city’s request. In July, the organization relocated everyone from the emergency shelter to Hotel Vertigo on Sutter Street, where her organization has managed 109 rooms, including a number of beds earmarked for LGBTQ residents.

Valdez knew the hotel wasn’t permanent, but didn’t expect the closures to arrive so soon. She found out that her hotel was scheduled to close through a city slideshow presentation. With her old shelter temporarily shuttered, and Hotel Vertigo in the city’s second phase for winddown, there’s nowhere to relocate the 70 hotel staffers employed by Dolores Street Community Services.

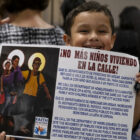

“They’ve been on the frontlines for nine months now,” Valdez said of her employees, who she described as largely working-class immigrants and people of color, many of whom live in multigenerational households. “I’ve had my staff tell me they have this rigorous routine of taking off all their clothing and putting them in plastic bags after work, not hugging their children, wearing masks at home, distancing themselves from their aging parents.”

Valdez said her employees have experienced extensive trauma working in the shelter setting, both personally, and vicariously through the homeless people they serve. “They worry — ‘What is going to happen if I get sick? What will happen to my family?’ — That is who has been the workforce serving the most vulnerable of our residents,” she said. “They are one step away from that vulnerability themselves.”

The picture is similar at Episcopal Community Services, which has traditionally managed several large San Francisco shelters, including NextDoor, a 334-bed facility, as well as the Central Waterfront Navigation Center and the Bryant Street Navigation Center. When those shelters closed, the staff followed residents to the shelter-in-place hotels.

“Many of these employees are longtimers at these organizations,” Bosio said. “You have folks who’ve worked in the shelter system 10, 15, 20 years, who’ve moved with their clients. They’re skilled workers who know the population, and are trained in de-escalation, how to address myriad mental health and substance use concerns, and just generally support folks coming off the street.”

While the city distributes funding for the hotels through the nonprofits that run them, there isn’t a budget set aside for compensating workers who face catastrophic layoffs. “As a union rep, I expect the city would offer a severance package,” Bosio added. “I would love to see them get a week’s pay for every year of service, plus a bonus for working a hazardous job. We went to employers and said you should go to the city and ask for the funding, and for extension of health coverage. They tried to negotiate, and it’s just a one-word reply: ‘No.’”

The city recently paused its closure timeline for the hotels, after news emerged from Sacramento that $62 million would be made available for sheltering vulnerable people in hotel rooms while the pandemic continues to rage. A detailed breakdown of how much would be allocated to San Francisco has yet to be released.

It could be good news for service providers; more than 75 organizations signed a letter addressed to Mayor London Breed on Thursday after the pause was announced, requesting that the hotel wind-down include a “realistic, well-resourced and compassionate plan” to permanently house residents and reassign workers.

“We’ll continue to advocate not only for our shelter-in-place hotel residents, but for our staff,” Valdez said. “We need to keep in mind the wellbeing of our workforce. When COVID is no longer here, we need that workforce to be with us as we rebuild, as we reopen our shelters, and we reopen our community.”